|

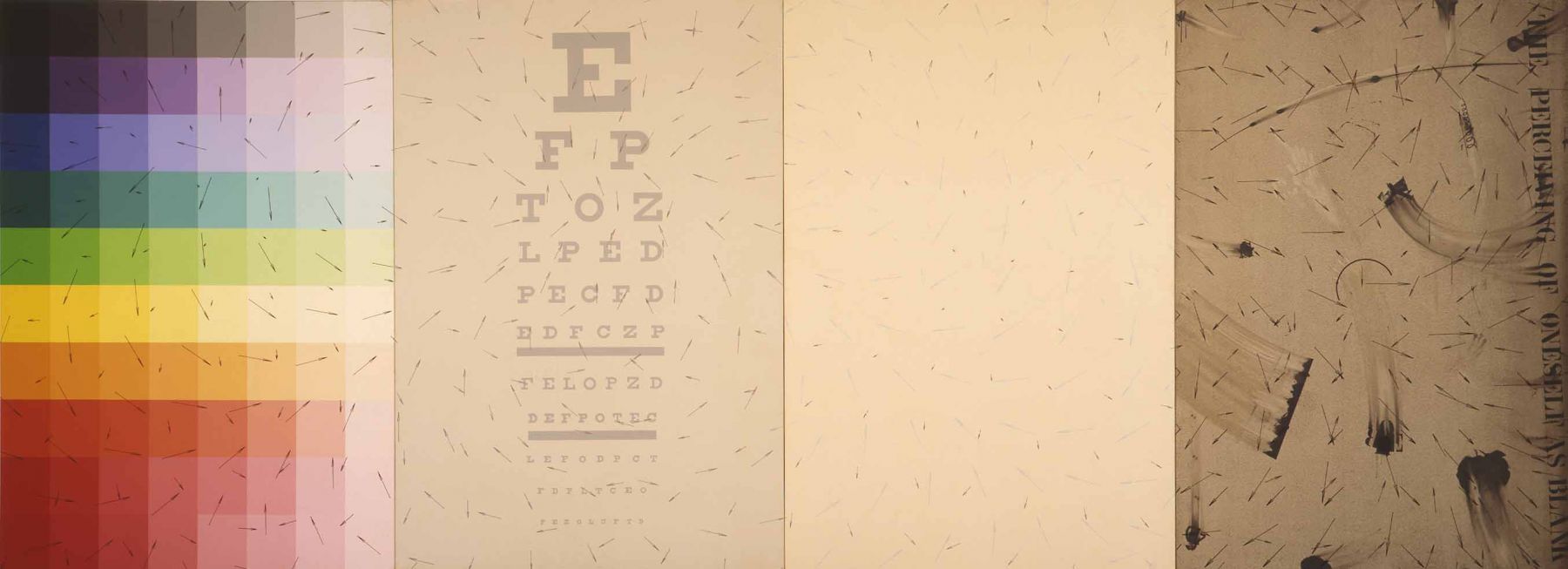

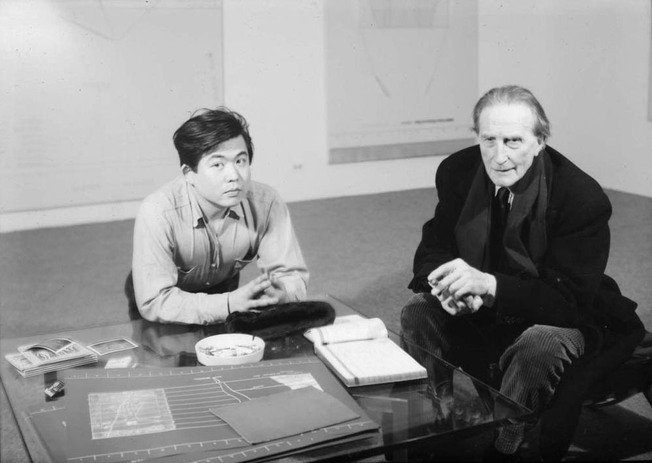

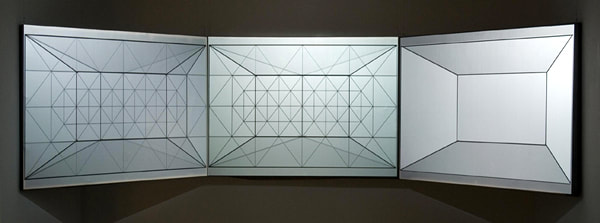

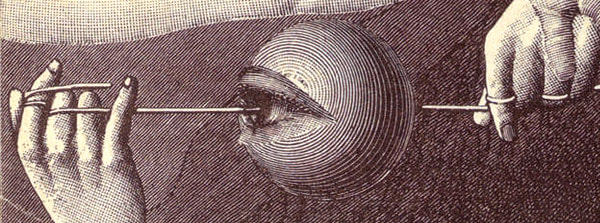

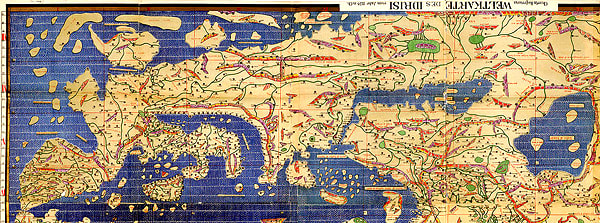

❉ Blog post 12 on diagrams in the arts and sciences introduces the diagrammatic practice of Arakawa and Gins, the diagram obsessed proteges of Marcel Duchamp. Figure 1: Blank Lines or Topological Bathing, 1980-81, acrylic on canvas, 254 x 691 cm © 2017 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins Whilst art students in Kyoto, my friends and I were invited by our teacher Usami Keiji to stay with him and his wife Sawako, at their cliff-top studios in Fukui, overlooking the sea of Japan. After a winding drive north through the mountains, we were met with an extravagant lunch of champagne, king crab, and one of Usami's arm-waving, hilarious, impromptu speeches on Foucault. Afterwards, a still-smiling Usami slid a book across the table between the bottles and empty red crab shells, saying only "This is a work of a genius". The book was 'The Mechanism of Meaning', a series of essays and photographs documenting the creation of eighty, large panel paintings made by the Japanese artist Shusaku Arakawa and his wife, the American poet, Madeline Gins, following a decade of collaboration between 1963 to 1973. Usami insisted I borrowed the book, but over the years whenever I tried to return it he would complain that it was too heavy for him to carry, and would ask me, smiling, to look after it well until the next time we met. Sadly, Usami passed away in 2012 and I still have his copy of the book, full of his own notes and comments in the margins about the work of two master diagram makers - Arakawa and Gins. As the legend goes, Arakawa arrived in New York with nothing but a few dollar bills and the telephone number of Marcel Duchamp. More importantly however, he carried with him a letter of recommendation from his mentor, the poet Shuzo Takeguchi, one of Japan's leading art critics and a champion of Surrealism in Japan. As a parting gift Takeguchi had given the young artist a book of his poetry, amongst the pages of which he had hidden a considerable sum of money for the young artist to later discover. Arakawa arrived to heavy snow at JFK airport in December 1961 and, using the little English he knew, made the fated phone call to Duchamp that would gain him not only immediate access to the very heart of New York's artistic community, but would see him become a protégé of Duchamp himself. Figure 2: Arakawa and Marcel Duchamp at Dwan Gallery, New York, 1966 © 2017 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins Duchamp arranged for Arakawa to stay in the loft apartment of Yoko Ono as she was away in Japan, and it was there that he met John Cage who had arranged to use the loft as a practice space for his group of musicians. It was also through Duchamp that Arakawa was introduced to Andy Warhol, whose attendance at Arakawa's early exhibitions brought a great deal of attention to the young, as yet unknown artist. The year after Arakawa arrival in New York he met Madeline Gins, and a year later they started work together on 'The Mechanism of Meaning', an ambitious collaboration that would take another ten years to complete.* (* Note: The series actually exists in two different versions, one at the Sezon Museum of Modern Art in Japan and the other in the holdings of the recently established 'Reversible destiny foundation' in New York, based in Arakawa and Gins former studio.)

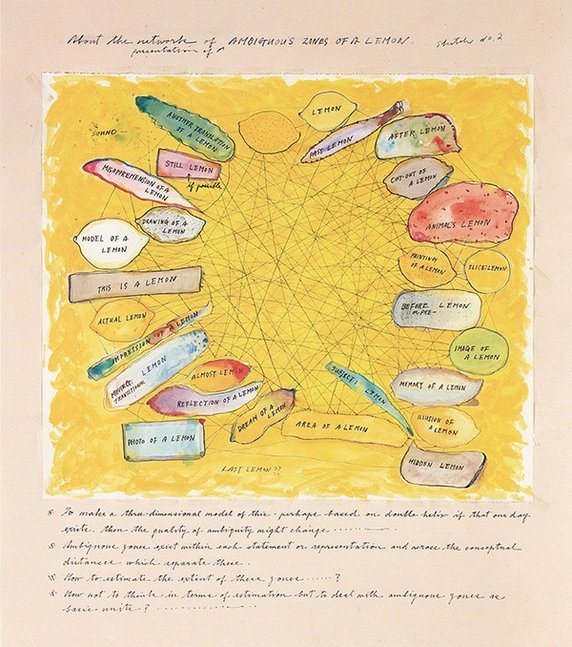

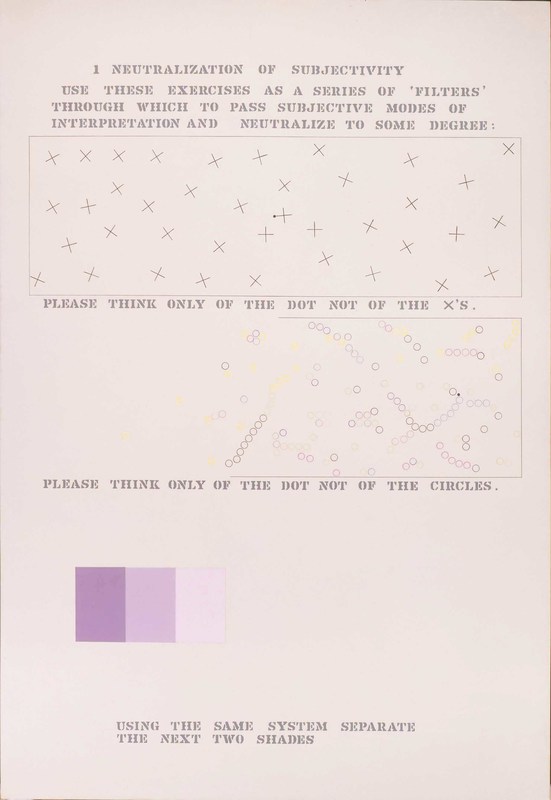

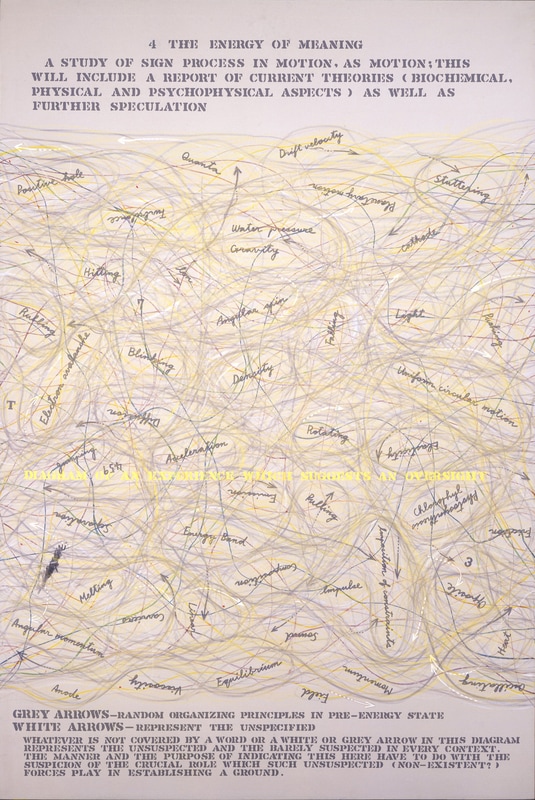

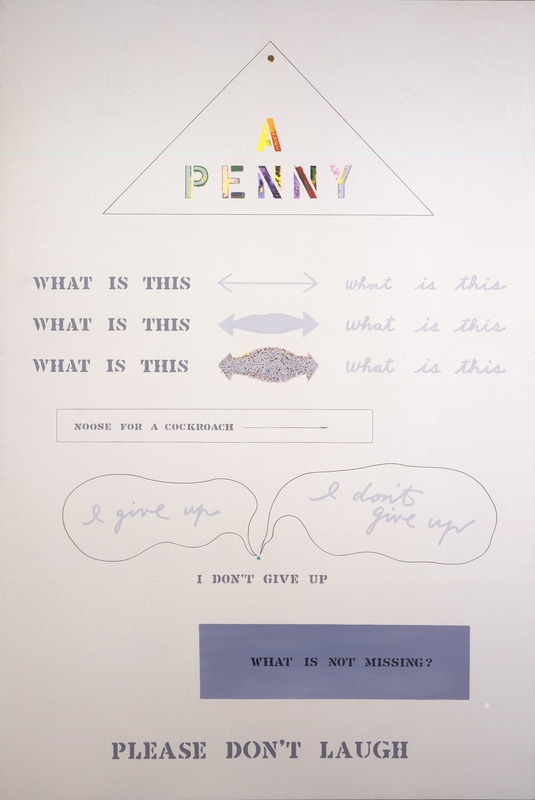

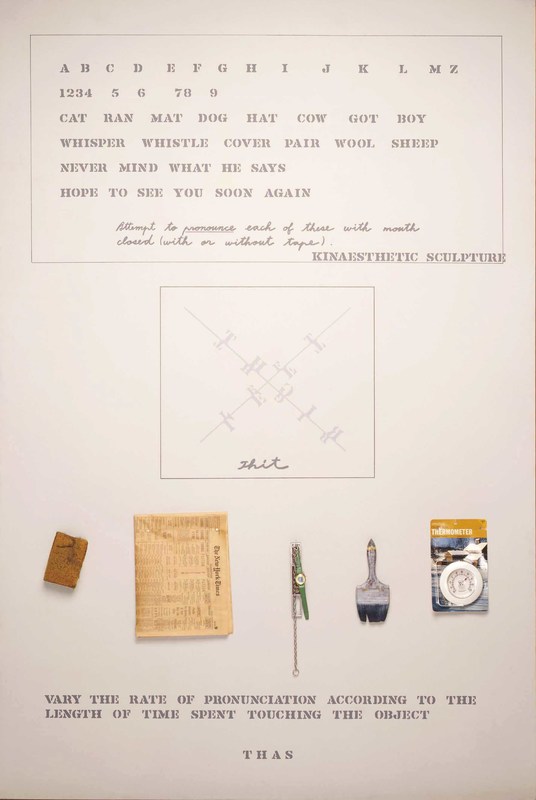

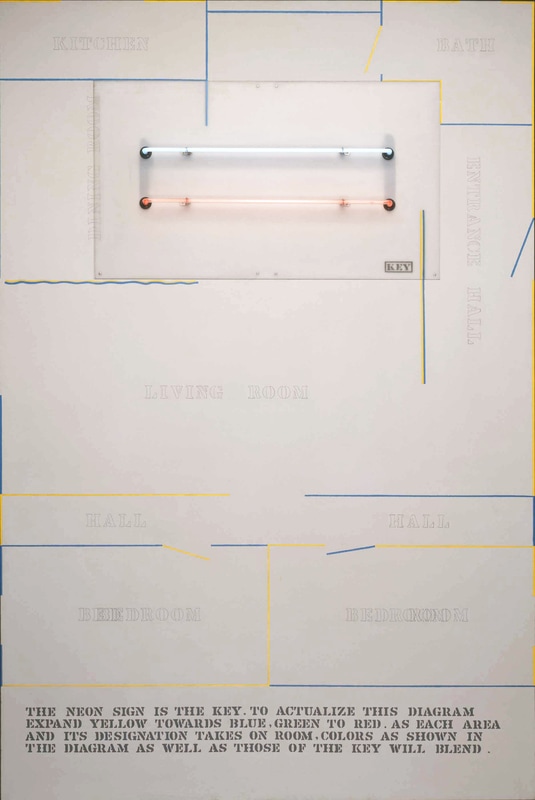

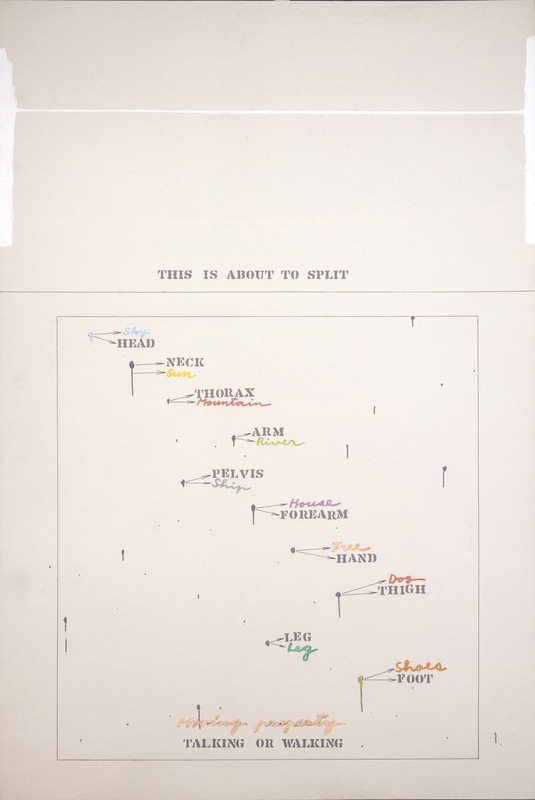

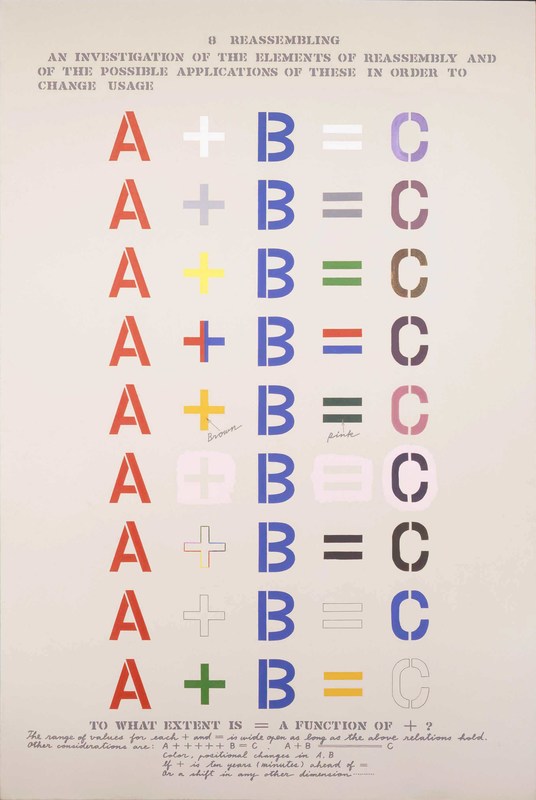

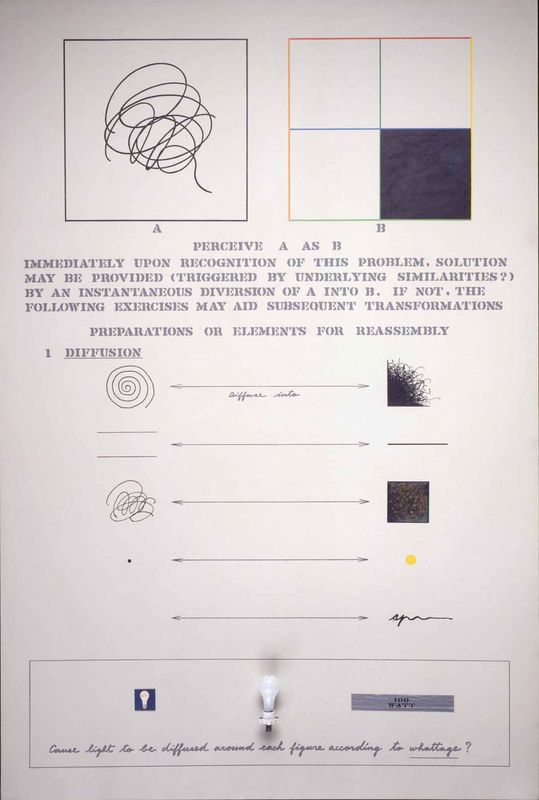

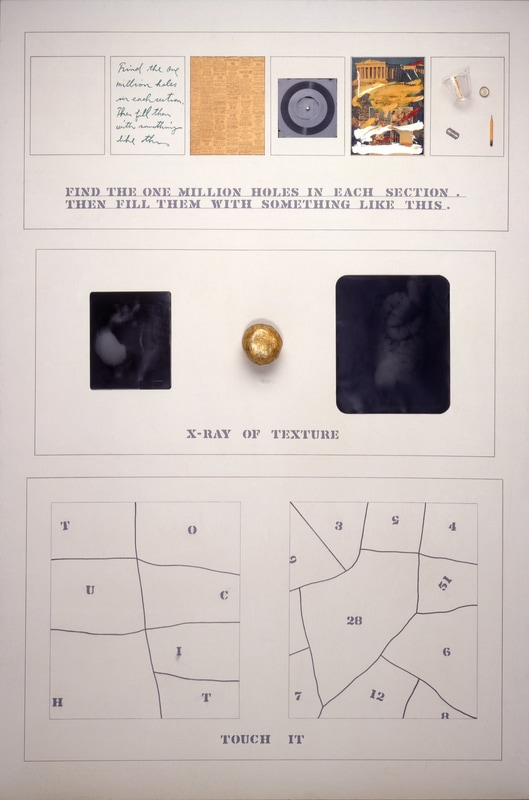

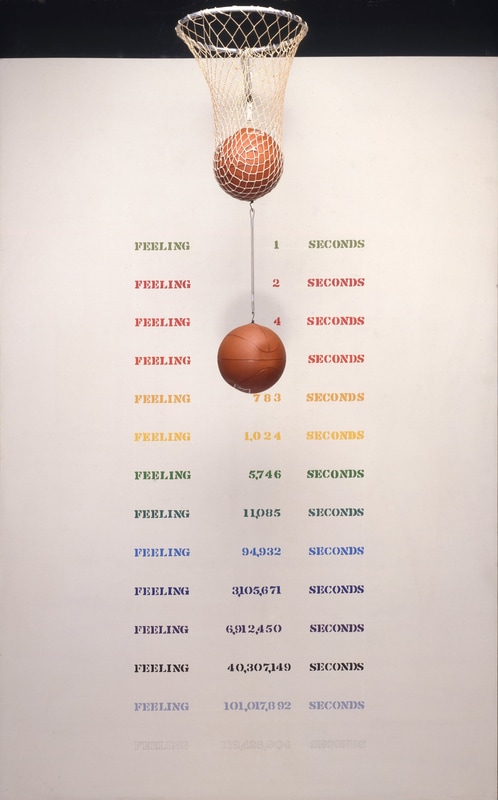

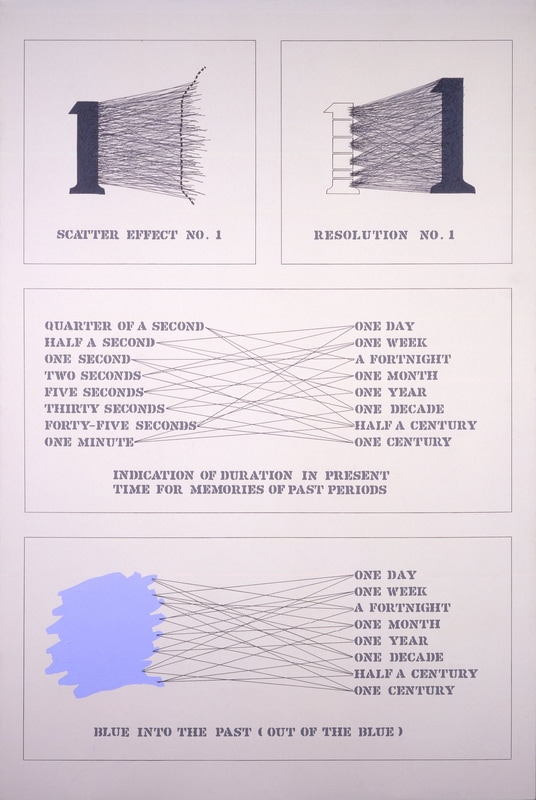

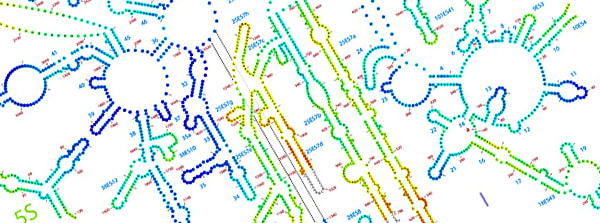

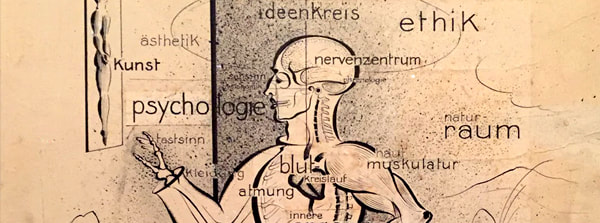

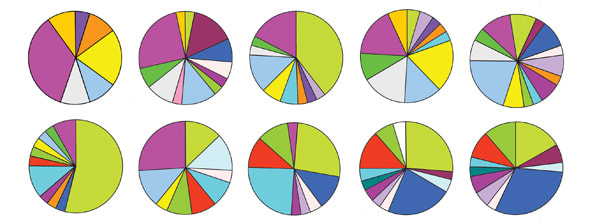

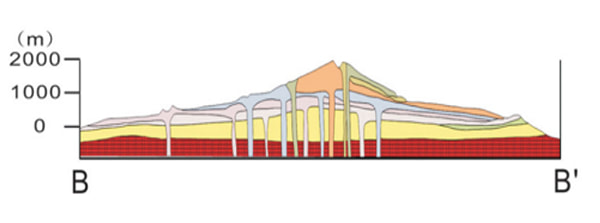

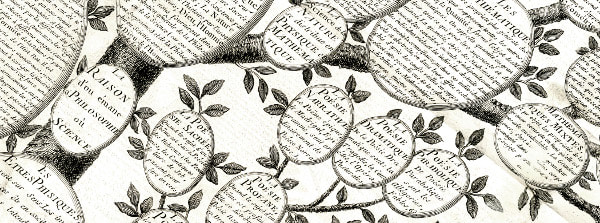

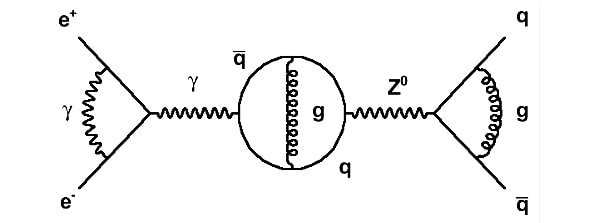

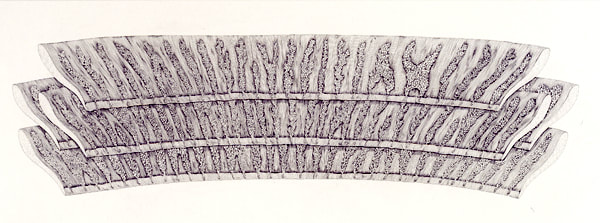

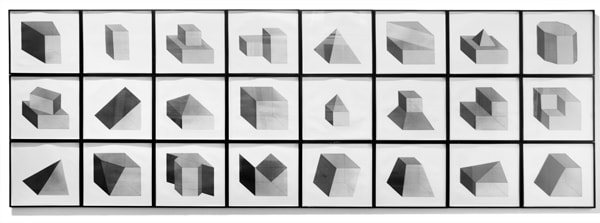

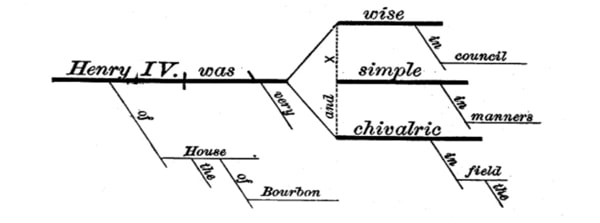

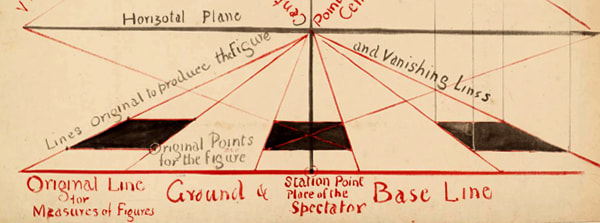

As described in an earlier blog post: " Coffee, diagrams, chocolate, masturbation ", diagrams were at the very heart of Marcel Duchamp's artistic practice and philosophy, having been educated at a time in France when sweeping reforms replaced traditional landscape and portrait studies with a fastidious training in diagrammatic draftsmanship. Duchamp's fascination with the reductive, refined aesthetics of diagrammatic images was clearly something he passed on to Arakawa, who developed his own obsession with diagrams and diagram making. His first solo exhibition in New York at the Dwan Gallery in 1966 was titled simply 'Arakawa: Diagrams', and the Gallerist Virginia Dwan later recalled how she had to dissuade the artist from wanting to sign his paintings 'Diagram', a move she felt was too abstract even for the New York art world. Early works such as 'Diagram with Duchamp’s Glass as a Minor Detail' (Figure 3) are evidence that Arakawa was all to aware of the profound influence his mentor was having upon his practice, and his desire to both pay homage and at the same time break orbit and seek out his own distinctive style. However Duchamp's diagrammatic art 'in service of the mind' would remain a major influence on both Arakawa and Gins as they developed their own master work - 'The Mechanism of Meaning'. Of the 80 panels that make up the series, one acts as an index by dividing the body of works into 16 different groups of paintings like chapters in a text book: 1) Neutralization of Subjectivity 2) Localization and Transference 3) Presentation of Ambiguous zones 4) The Energy of Meaning (Biochemical, Physical, and Psychophysical aspects) 5) Degrees of meaning 6) Expansion and Reduction - Meaning of Scale 7) Splitting of Meaning 8) Reassembling 9) Reversibility 10) Texture of Meaning 11) Mapping of Meaning 12) Feeling of Meaning 13) Logic of Meaning 14) Construction of the Memory of Meaning 15) Review and Self-Criticism 'The Mechanism of Meaning' consists a number of self-contradictory puzzles, instructions and statements presented in a variety of diagrammatic formats. Gins' wide-ranging studies are evident in the works, which reference Oriental philosophy, Japanese and Chinese poetry, English and Physics. Gins also took art classes at the Brooklyn Museum, and it was here that she first met her fellow student Arakawa (who later claimed that he enrolled only in order to extend his American visa). When engaging with 'The Mechanism of Meaning', the panels act in a way like mirrors to the thought processes being used to analyse them, a kind of self referential, recursive process reminiscent of Douglas Hofstadter idea of 'a strange loops'. Many of the texts in the paintings resemble 'Koans' from Zen Buddhism, short puzzles designed to be meditated upon by monks during their training. Viewers of 'The Mechanism of Meaning' are instructed to 'Turn left as you turn right', or to picture a 'Mnemonic device for forgetting' and then 'Imagine a thought which bypasses everything'. Zen Koans are intended to jolt the thinker in to a state of enlightenment through paradox, and the project won Arakawa and Gins a host of intellectual admirers including Italo Calvino, who wrote how "An Arakawa painting seems precisely cut out to contain the mind, or to be contained in it… After studying one of Arakawa’s paintings it is I who begin to feel that my mind is ‘like’ the picture" (1). The French Philosopher Jean-Francois Lyotard described how the work of Arakawa and Gins “makes us think through the eyes.” (2) Such an poignant image is reminiscent of the American Philosopher C.S. Peirce's description of diagrams as 'moving pictures of thought'. Figure 4: 'About the network of ( perception of ) AMBIGUOUS ZONES OF A LEMON (Sketch No.2)', Ink on paper, from “The Mechanism of Meaning” c. 1963 – 88, Ink on paper (size unknown) Copyright credit: © 2017 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins and Reversible Destiny Foundation. Figure 4 is a sketch for the panel 'Ambiguous zones of a Lemon', and consists of an entangled network that diagrams the various ways we can consider a lemon. What at first appears to be a humorous take on a lemon's multiple, nuanced qualities, in fact turns out to reveal a great deal about the complex relationship between our objective and subjectively descriptions of reality. To paraphrase the British philosopher Bertrand Russell: an observer, when he feels himself to himself to be observing a stone (or, in Arakawa's case, a lemon), is really, if physics is to be believed, observing the effects of the stone upon himself (3). The distinction between subjective and objective qualities is of fundamental importance to the philosophy of science, where qualities are divided in to primary (those that exist independent of an observer, such as quantity and mass), and secondary (those given by the human senses to an object, such as colour, taste and smell). The categories of Arakawa and Gins play with these distinctions, allowing them to resonate in a way that I term 'Romantic - Objective'. Categories of ambiguous zones:

'The Mechanism of Meaning' series is akin to Duchamp's idea of a 'playful physics', in which objectivity and systems of scientific measure and analysis are taken to their limits, in order to reveal their tenuous philosophical underpinnings. The aim of such an approach isn't simply to undermine the scientific process, for, in the words of Arakawa himself, "If you want to become an artist, you have to become a scientist first." (4) Rather the aim is to creatively test the limits of thought and logic in a way similar to the Philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein, the work of whom Arakawa and Gins had read and would discuss at length in their studio. (The style of Wittgenstein's 'Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus' becomes immediately apparent when viewing 'The mechanism of Meaning'.) Gins and Arakawa created a rich new vocabulary to map out the poetic-conceptual terrain their work explored, and their terminology is suggestive of entirely new fields of study. Rather than refer to himself an artist, Arakawa pronounced himself a 'coordinologist', and Gins described herself as a 'biotopologist', and both continued to engage in frequent discussions with philosophers and scientists. 'The Mechanism of Meaning gained world-wide success in the 1970's, and was shown in it's entirety at the Venice Biennale in 1970, and again in Germany in 1972, where it was praised by the renowned German theoretical physicist Werner Heisenberg, winner of the 1932 Nobel prize in physics, who invited Arakawa and Gins as artists in residence at the prestigious Max-Planck-Institute. Heisenberg has the so called 'uncertainty principle' named after him, and it's easy to imagine the appeal that 'The Mechanism of Meaning' had to a mind used to struggling with the indeterminate nature of reality at it's most fundamental level. Below are a series of selected panels from the 'The Mechanism of Meaning' series. I would like to thank the Estate of Madeline Gins and the Reversible Destiny Foundation for permission to use these images, and more information can be found at the Reversible Destiny Foundation homepage, or by following their facebook page here. The foundation recently announced that they will be working together with Gagosian gallery to fully document and represent 'The Mechanism of Meaning' series, in order to bring this important and still highly relevant work Arakawa and Gins to a contemporary audience.

References: 1) Italo Calvino, The arrow in the mind: A review of the Mechanism of Meaning. In: Image, Eye and Art in Calvino: Writing Visibility. 2007, Chpr 20.

2) Lyotard, J.F, In: Reversible Destiny, Arakawa / Gins, Guggenheim Museum Publication, 1997. 3) Bertrand Russell, An inquiry into meaning and truth: The William James lectures for 1940 delivered at Harvard University, London Routledge, 1992, p.72. 4) Arakawa speaking in the film Children Who Won’t Die (2010) Directed by Nobu Yamaoka. 5) Peirce, C.S, quoted in: Brent, J. Charles Sanders Peirce: A life, 1998, Indiana Uni. Press, p.129

2 Comments

Daniel Volz

7/22/2020 07:31:32 am

Wanderings within chaos and order

Reply

vila jean-louis

7/23/2020 06:40:22 am

je suis très ému, de retrouver Arakawa

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Dr. Michael WhittleBritish artist and Posts:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|