|

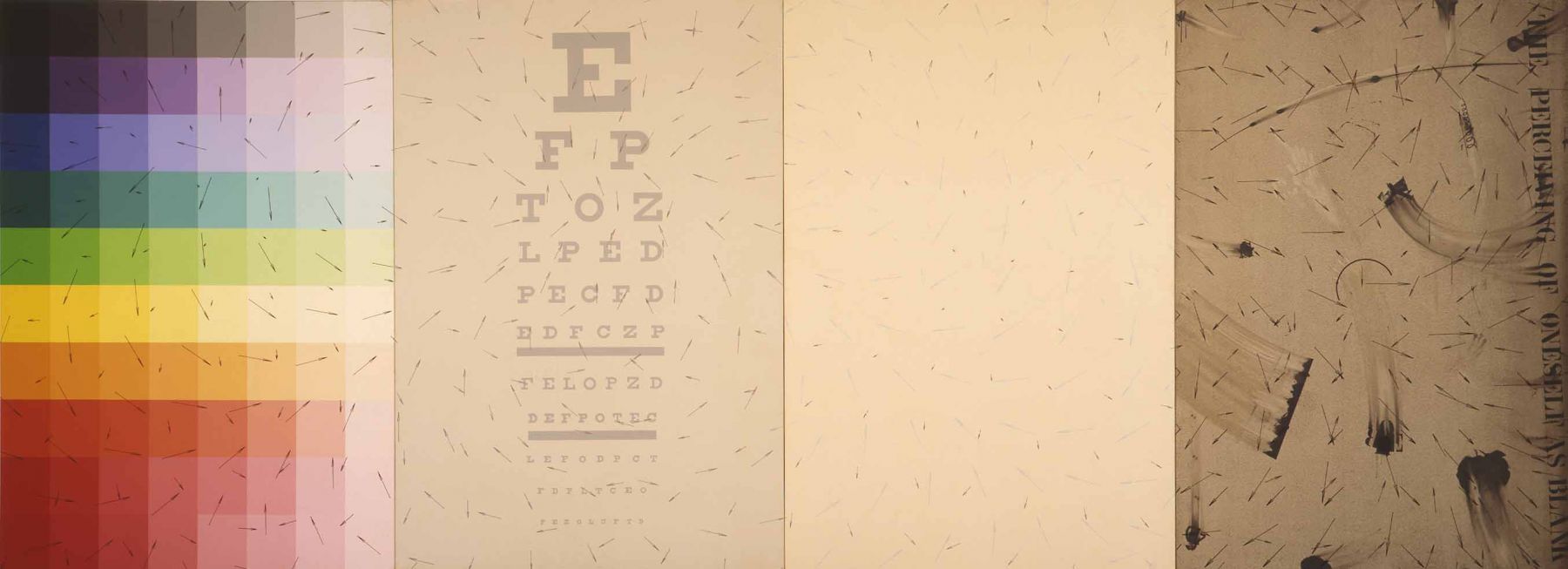

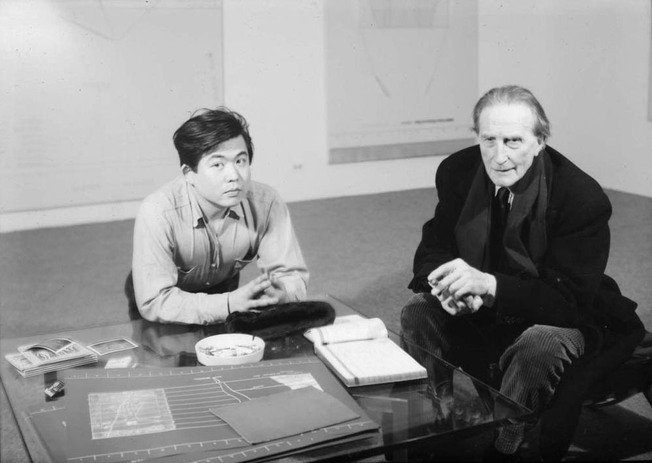

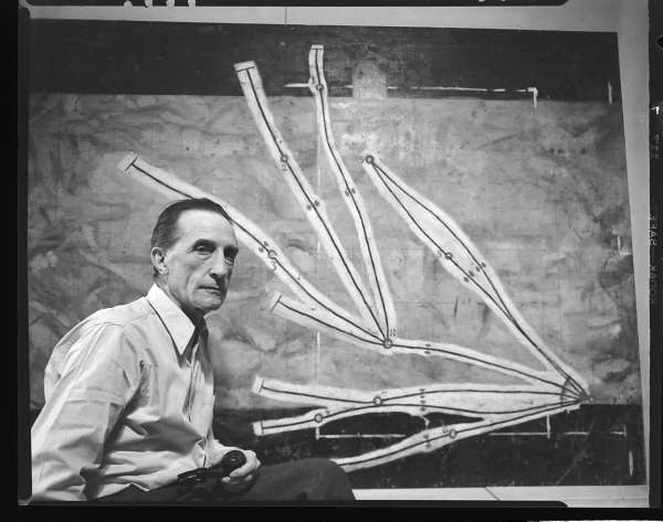

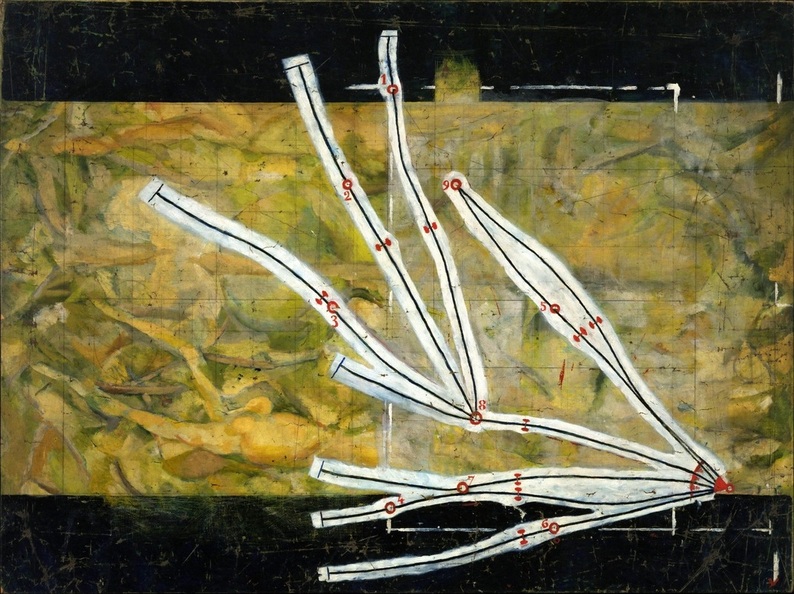

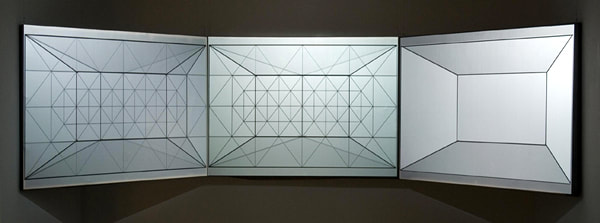

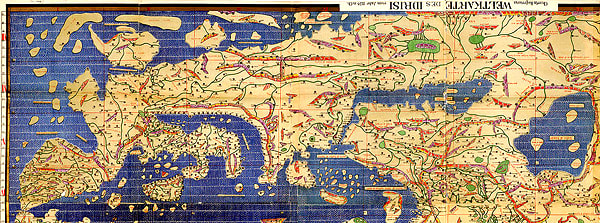

❉ Blog post 12 on diagrams in the arts and sciences introduces the diagrammatic practice of Arakawa and Gins, the diagram obsessed proteges of Marcel Duchamp. Figure 1: Blank Lines or Topological Bathing, 1980-81, acrylic on canvas, 254 x 691 cm © 2017 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins Whilst art students in Kyoto, my friends and I were invited by our teacher Usami Keiji to stay with him and his wife Sawako, at their cliff-top studios in Fukui, overlooking the sea of Japan. After a winding drive north through the mountains, we were met with an extravagant lunch of champagne, king crab, and one of Usami's arm-waving, hilarious, impromptu speeches on Foucault. Afterwards, a still-smiling Usami slid a book across the table between the bottles and empty red crab shells, saying only "This is a work of a genius". The book was 'The Mechanism of Meaning', a series of essays and photographs documenting the creation of eighty, large panel paintings made by the Japanese artist Shusaku Arakawa and his wife, the American poet, Madeline Gins, following a decade of collaboration between 1963 to 1973. Usami insisted I borrowed the book, but over the years whenever I tried to return it he would complain that it was too heavy for him to carry, and would ask me, smiling, to look after it well until the next time we met. Sadly, Usami passed away in 2012 and I still have his copy of the book, full of his own notes and comments in the margins about the work of two master diagram makers - Arakawa and Gins. As the legend goes, Arakawa arrived in New York with nothing but a few dollar bills and the telephone number of Marcel Duchamp. More importantly however, he carried with him a letter of recommendation from his mentor, the poet Shuzo Takeguchi, one of Japan's leading art critics and a champion of Surrealism in Japan. As a parting gift Takeguchi had given the young artist a book of his poetry, amongst the pages of which he had hidden a considerable sum of money for the young artist to later discover. Arakawa arrived to heavy snow at JFK airport in December 1961 and, using the little English he knew, made the fated phone call to Duchamp that would gain him not only immediate access to the very heart of New York's artistic community, but would see him become a protégé of Duchamp himself. Figure 2: Arakawa and Marcel Duchamp at Dwan Gallery, New York, 1966 © 2017 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins Duchamp arranged for Arakawa to stay in the loft apartment of Yoko Ono as she was away in Japan, and it was there that he met John Cage who had arranged to use the loft as a practice space for his group of musicians. It was also through Duchamp that Arakawa was introduced to Andy Warhol, whose attendance at Arakawa's early exhibitions brought a great deal of attention to the young, as yet unknown artist. The year after Arakawa arrival in New York he met Madeline Gins, and a year later they started work together on 'The Mechanism of Meaning', an ambitious collaboration that would take another ten years to complete.* (* Note: The series actually exists in two different versions, one at the Sezon Museum of Modern Art in Japan and the other in the holdings of the recently established 'Reversible destiny foundation' in New York, based in Arakawa and Gins former studio.)

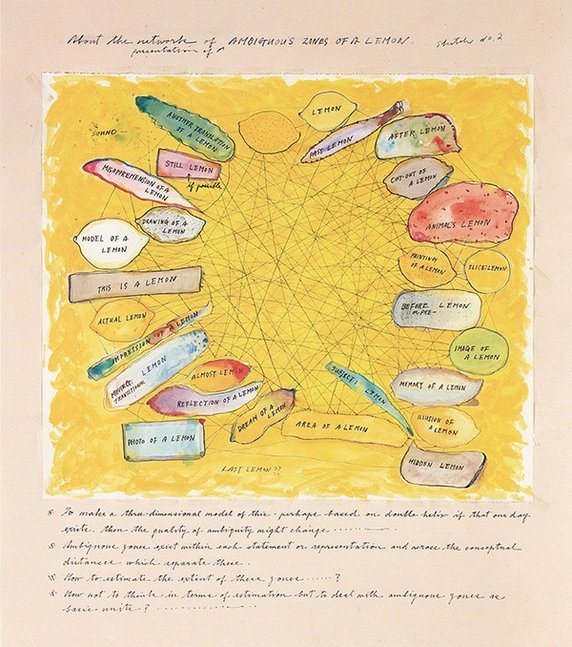

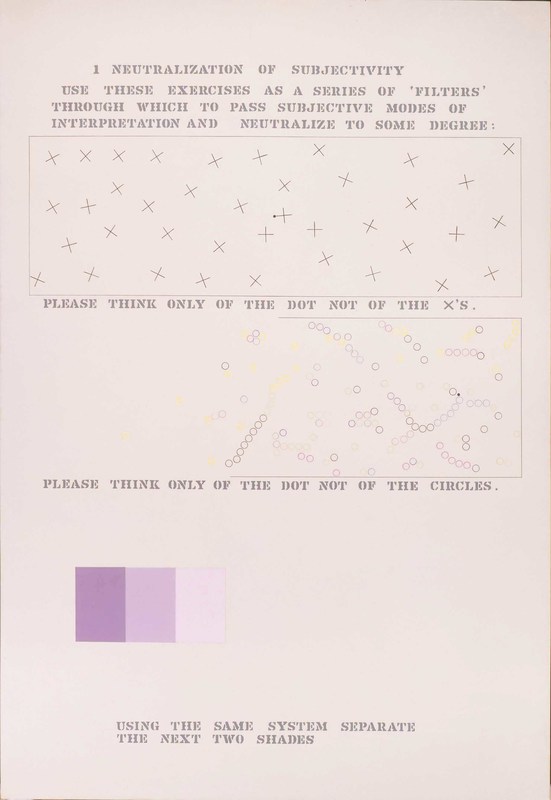

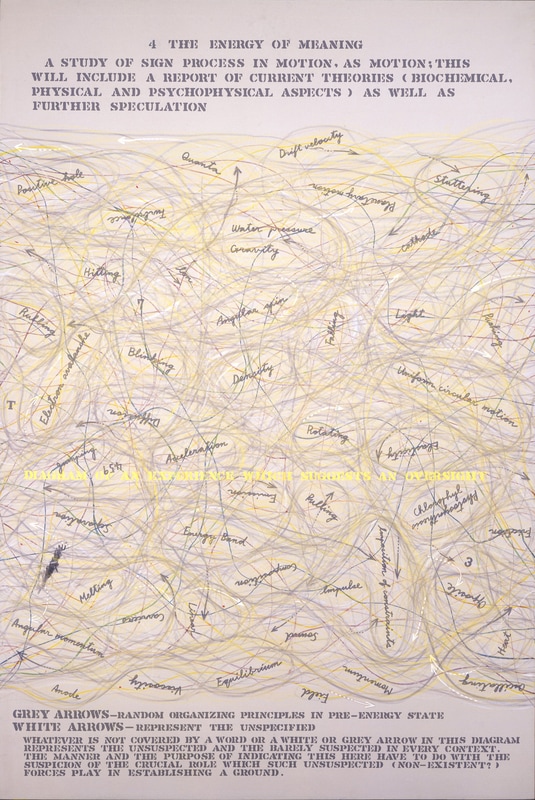

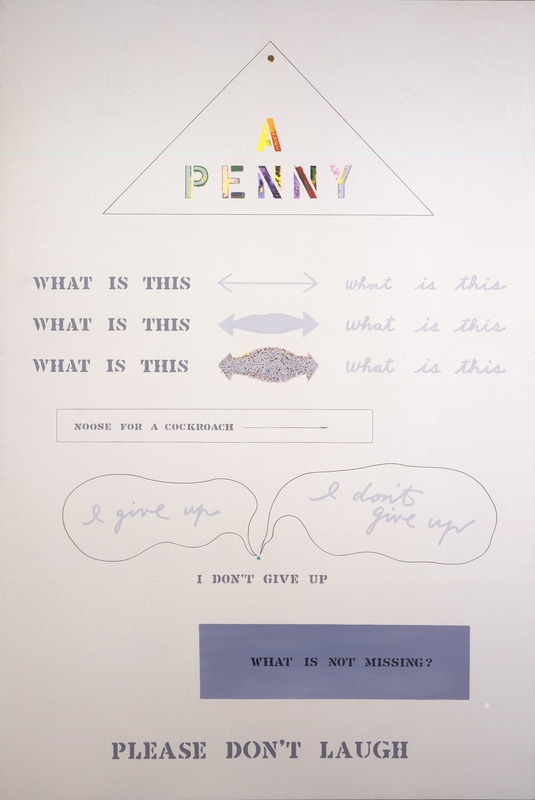

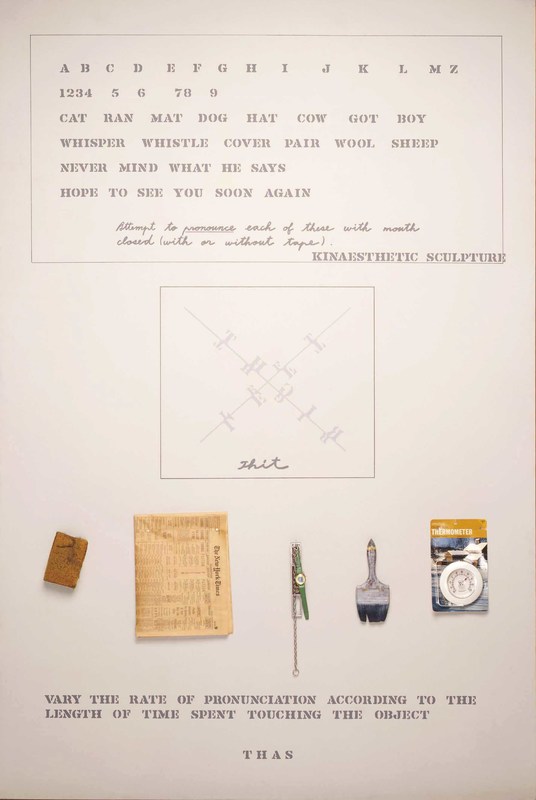

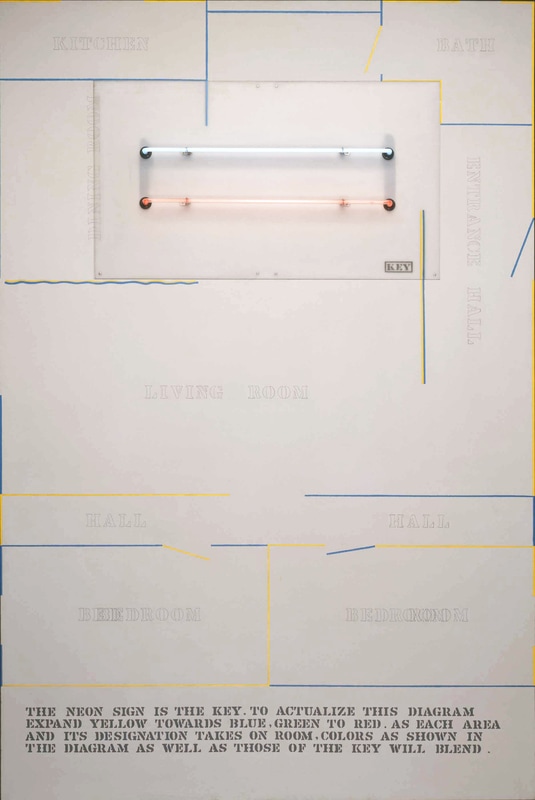

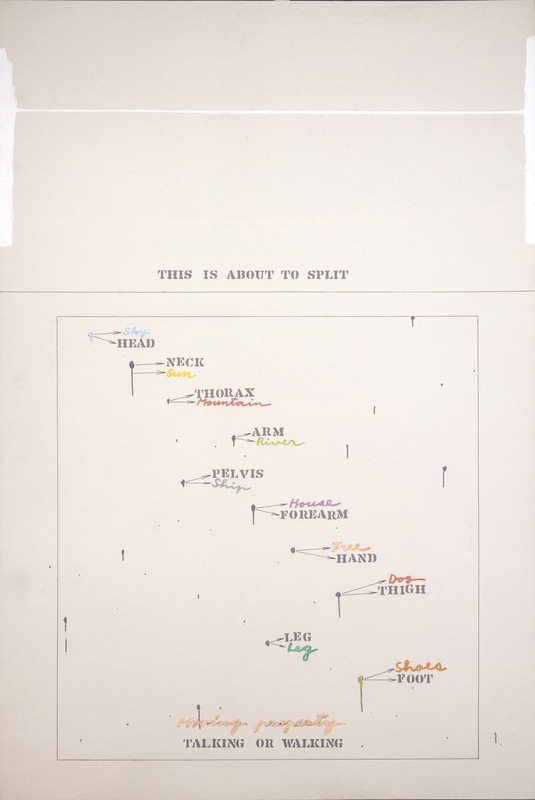

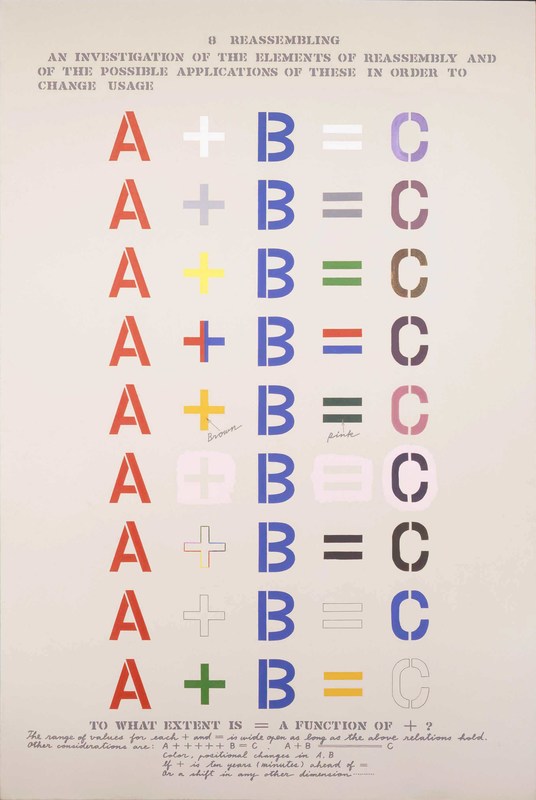

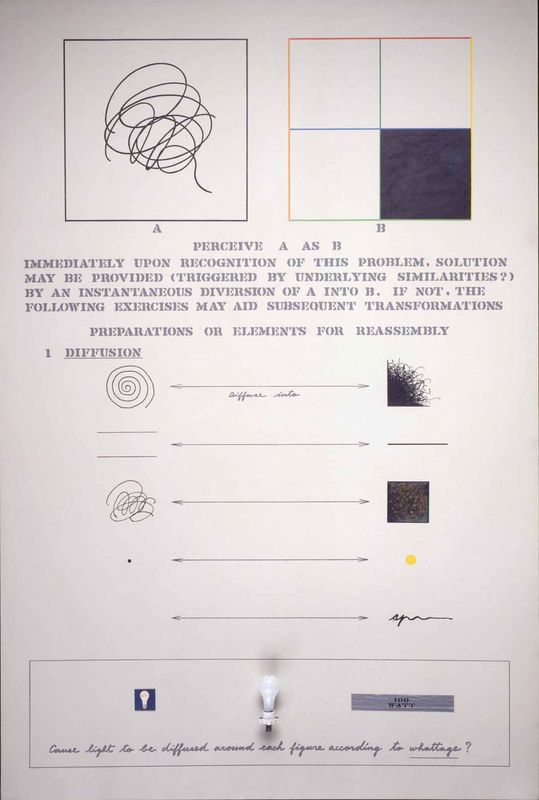

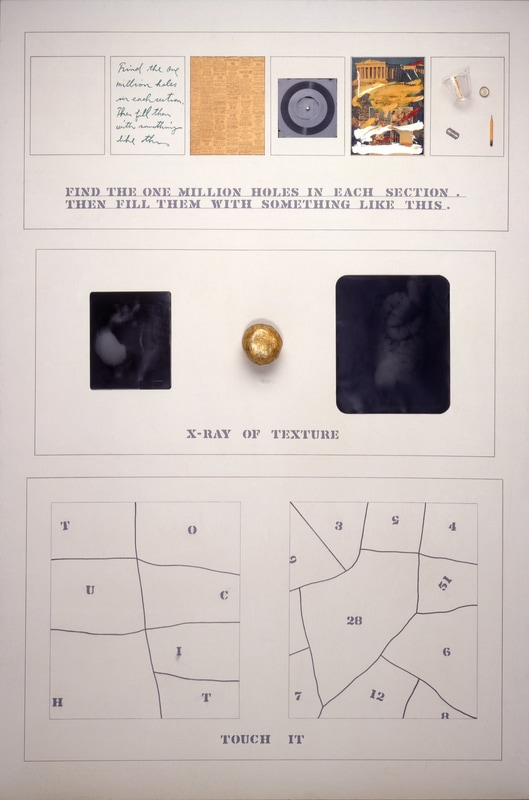

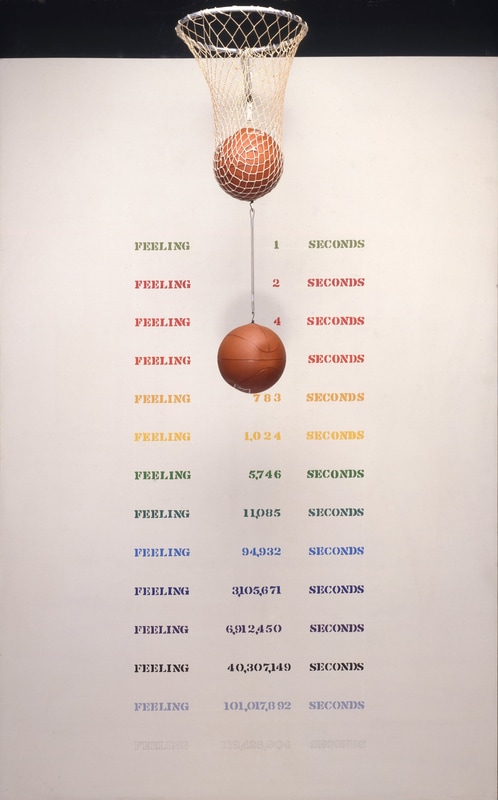

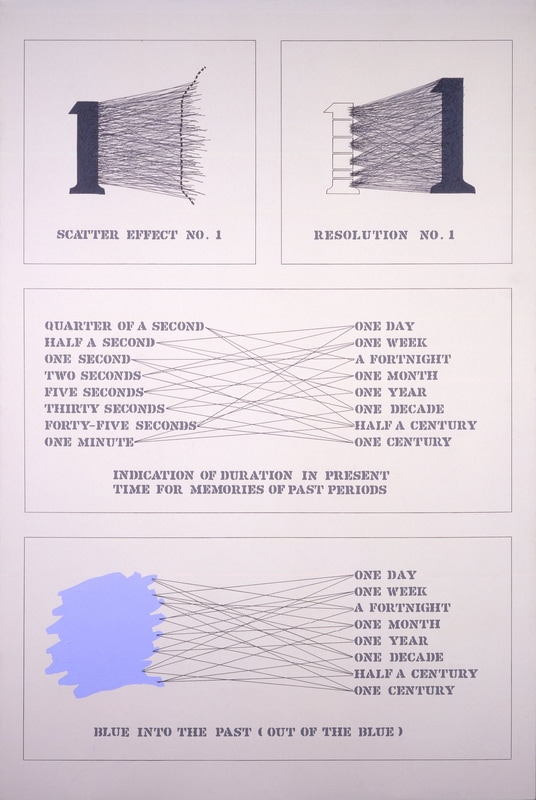

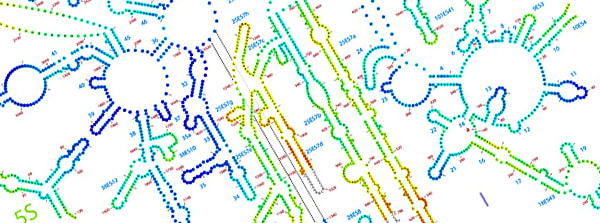

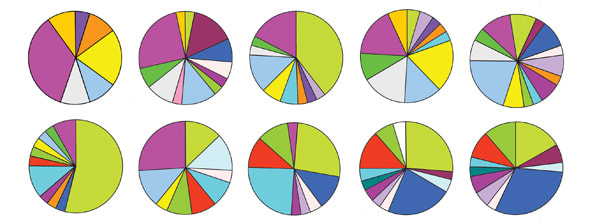

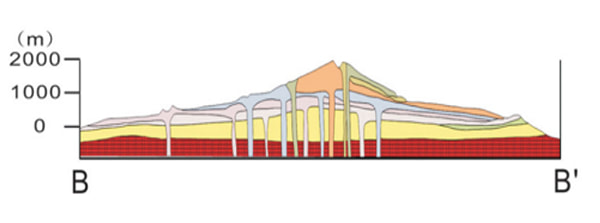

As described in an earlier blog post: " Coffee, diagrams, chocolate, masturbation ", diagrams were at the very heart of Marcel Duchamp's artistic practice and philosophy, having been educated at a time in France when sweeping reforms replaced traditional landscape and portrait studies with a fastidious training in diagrammatic draftsmanship. Duchamp's fascination with the reductive, refined aesthetics of diagrammatic images was clearly something he passed on to Arakawa, who developed his own obsession with diagrams and diagram making. His first solo exhibition in New York at the Dwan Gallery in 1966 was titled simply 'Arakawa: Diagrams', and the Gallerist Virginia Dwan later recalled how she had to dissuade the artist from wanting to sign his paintings 'Diagram', a move she felt was too abstract even for the New York art world. Early works such as 'Diagram with Duchamp’s Glass as a Minor Detail' (Figure 3) are evidence that Arakawa was all to aware of the profound influence his mentor was having upon his practice, and his desire to both pay homage and at the same time break orbit and seek out his own distinctive style. However Duchamp's diagrammatic art 'in service of the mind' would remain a major influence on both Arakawa and Gins as they developed their own master work - 'The Mechanism of Meaning'. Of the 80 panels that make up the series, one acts as an index by dividing the body of works into 16 different groups of paintings like chapters in a text book: 1) Neutralization of Subjectivity 2) Localization and Transference 3) Presentation of Ambiguous zones 4) The Energy of Meaning (Biochemical, Physical, and Psychophysical aspects) 5) Degrees of meaning 6) Expansion and Reduction - Meaning of Scale 7) Splitting of Meaning 8) Reassembling 9) Reversibility 10) Texture of Meaning 11) Mapping of Meaning 12) Feeling of Meaning 13) Logic of Meaning 14) Construction of the Memory of Meaning 15) Review and Self-Criticism 'The Mechanism of Meaning' consists a number of self-contradictory puzzles, instructions and statements presented in a variety of diagrammatic formats. Gins' wide-ranging studies are evident in the works, which reference Oriental philosophy, Japanese and Chinese poetry, English and Physics. Gins also took art classes at the Brooklyn Museum, and it was here that she first met her fellow student Arakawa (who later claimed that he enrolled only in order to extend his American visa). When engaging with 'The Mechanism of Meaning', the panels act in a way like mirrors to the thought processes being used to analyse them, a kind of self referential, recursive process reminiscent of Douglas Hofstadter idea of 'a strange loops'. Many of the texts in the paintings resemble 'Koans' from Zen Buddhism, short puzzles designed to be meditated upon by monks during their training. Viewers of 'The Mechanism of Meaning' are instructed to 'Turn left as you turn right', or to picture a 'Mnemonic device for forgetting' and then 'Imagine a thought which bypasses everything'. Zen Koans are intended to jolt the thinker in to a state of enlightenment through paradox, and the project won Arakawa and Gins a host of intellectual admirers including Italo Calvino, who wrote how "An Arakawa painting seems precisely cut out to contain the mind, or to be contained in it… After studying one of Arakawa’s paintings it is I who begin to feel that my mind is ‘like’ the picture" (1). The French Philosopher Jean-Francois Lyotard described how the work of Arakawa and Gins “makes us think through the eyes.” (2) Such an poignant image is reminiscent of the American Philosopher C.S. Peirce's description of diagrams as 'moving pictures of thought'. Figure 4: 'About the network of ( perception of ) AMBIGUOUS ZONES OF A LEMON (Sketch No.2)', Ink on paper, from “The Mechanism of Meaning” c. 1963 – 88, Ink on paper (size unknown) Copyright credit: © 2017 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins and Reversible Destiny Foundation. Figure 4 is a sketch for the panel 'Ambiguous zones of a Lemon', and consists of an entangled network that diagrams the various ways we can consider a lemon. What at first appears to be a humorous take on a lemon's multiple, nuanced qualities, in fact turns out to reveal a great deal about the complex relationship between our objective and subjectively descriptions of reality. To paraphrase the British philosopher Bertrand Russell: an observer, when he feels himself to himself to be observing a stone (or, in Arakawa's case, a lemon), is really, if physics is to be believed, observing the effects of the stone upon himself (3). The distinction between subjective and objective qualities is of fundamental importance to the philosophy of science, where qualities are divided in to primary (those that exist independent of an observer, such as quantity and mass), and secondary (those given by the human senses to an object, such as colour, taste and smell). The categories of Arakawa and Gins play with these distinctions, allowing them to resonate in a way that I term 'Romantic - Objective'. Categories of ambiguous zones:

'The Mechanism of Meaning' series is akin to Duchamp's idea of a 'playful physics', in which objectivity and systems of scientific measure and analysis are taken to their limits, in order to reveal their tenuous philosophical underpinnings. The aim of such an approach isn't simply to undermine the scientific process, for, in the words of Arakawa himself, "If you want to become an artist, you have to become a scientist first." (4) Rather the aim is to creatively test the limits of thought and logic in a way similar to the Philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein, the work of whom Arakawa and Gins had read and would discuss at length in their studio. (The style of Wittgenstein's 'Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus' becomes immediately apparent when viewing 'The mechanism of Meaning'.) Gins and Arakawa created a rich new vocabulary to map out the poetic-conceptual terrain their work explored, and their terminology is suggestive of entirely new fields of study. Rather than refer to himself an artist, Arakawa pronounced himself a 'coordinologist', and Gins described herself as a 'biotopologist', and both continued to engage in frequent discussions with philosophers and scientists. 'The Mechanism of Meaning gained world-wide success in the 1970's, and was shown in it's entirety at the Venice Biennale in 1970, and again in Germany in 1972, where it was praised by the renowned German theoretical physicist Werner Heisenberg, winner of the 1932 Nobel prize in physics, who invited Arakawa and Gins as artists in residence at the prestigious Max-Planck-Institute. Heisenberg has the so called 'uncertainty principle' named after him, and it's easy to imagine the appeal that 'The Mechanism of Meaning' had to a mind used to struggling with the indeterminate nature of reality at it's most fundamental level. Below are a series of selected panels from the 'The Mechanism of Meaning' series. I would like to thank the Estate of Madeline Gins and the Reversible Destiny Foundation for permission to use these images, and more information can be found at the Reversible Destiny Foundation homepage, or by following their facebook page here. The foundation recently announced that they will be working together with Gagosian gallery to fully document and represent 'The Mechanism of Meaning' series, in order to bring this important and still highly relevant work Arakawa and Gins to a contemporary audience.

References: 1) Italo Calvino, The arrow in the mind: A review of the Mechanism of Meaning. In: Image, Eye and Art in Calvino: Writing Visibility. 2007, Chpr 20.

2) Lyotard, J.F, In: Reversible Destiny, Arakawa / Gins, Guggenheim Museum Publication, 1997. 3) Bertrand Russell, An inquiry into meaning and truth: The William James lectures for 1940 delivered at Harvard University, London Routledge, 1992, p.72. 4) Arakawa speaking in the film Children Who Won’t Die (2010) Directed by Nobu Yamaoka. 5) Peirce, C.S, quoted in: Brent, J. Charles Sanders Peirce: A life, 1998, Indiana Uni. Press, p.129

2 Comments

The diagrams of geometry - part 2: A soggy book of diagrams as a wedding present from Marcel Duchamp10/20/2016

❉ This is the ninth in a series of blogs that discuss diagrams and the diagrammatic format, especially in relation to fine art. I recently completed my PhD on this subject at Kyoto city university of the arts, Japan's oldest art school.

Feel free to leave comments or to contact me directly if you'd like any more information on life as an artist in Japan, what a PhD in Fine Art involves, applying for the Japanese government Monbusho scholarship program (MEXT), or to talk about diagrams and diagrammatic art in general.

Figure 1: Portrait of Marcel Duchamp for Life Magazine taken in 1952 by Gordon Parks,

in front of Network of Stoppages (1914), Oil and pencil on canvas, 148.9 x 198.12 cm

The young modernist poet, dramatist and writer Jacques Nayral (a pseudonym for Joseph Houot) wrote the forward to the catalogue for the 1912 exhibition of Cubist art "Exposicion d'art cubista" at the Dalmau Gallery in Barcelona. Nayral described how “[t]he Mathematical spirit seems to dominate Marcel Duchamp. Some of his pictures are pure diagrams, as if he were striving for proofs and synthesis.” (1)

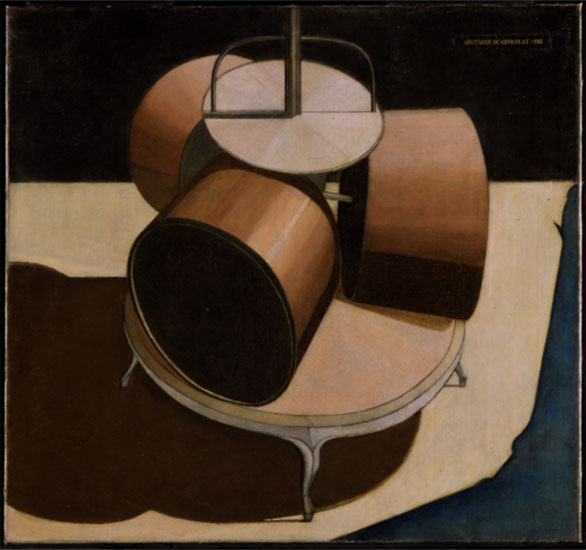

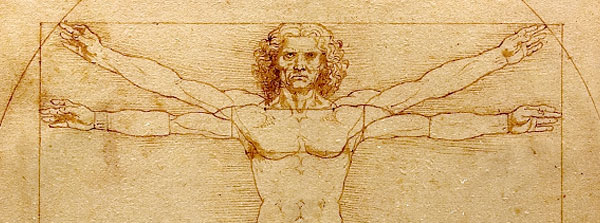

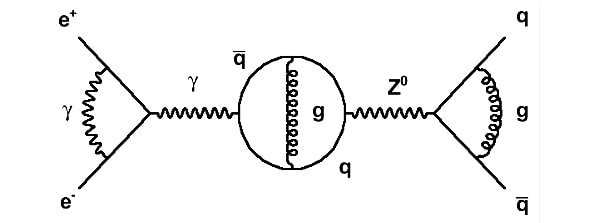

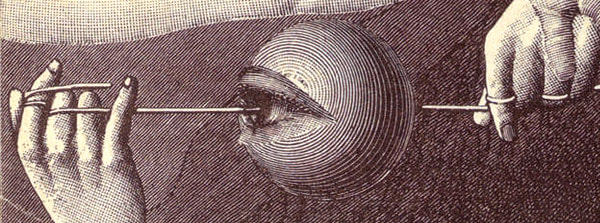

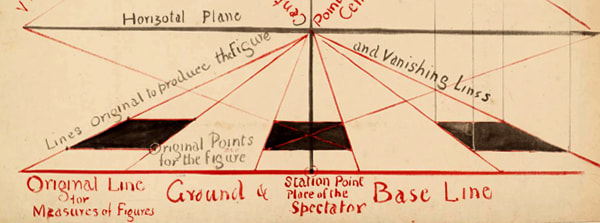

We have already seen in a previous post how Duchamp's training as a young artist was founded upon the diagram, having studied during a period in France when students were made to practice mechanical drawing as opposed to the traditional historical modes of figurative and landscape. Trained in ‘the language of industry’, (2) Duchamp remained fascinated with the detached, objective qualities of technical diagrammatic drawings, proclaiming his desire to create “paintings of precision” with a “beauty of indifference.” (3) He also spoke in interview of how he wished to "go back to a completely dry drawing, a dry conception of art. I was beginning to appreciate the value of exactness, of precision and the importance of chance… And the mechanical drawing was for me the best form of that dry conception of art… a mechanical drawing has no taste in it. (4)

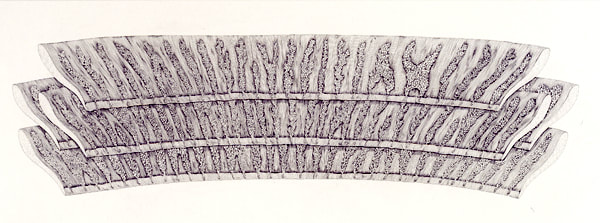

The steps Duchamp took to refine his work towards being beautifully indifferent images of precision are visible in the two paintings above, made within a year of each other. Chocolate grinder number 1 (1913) is painted in traditional perspective and the illusion of three dimensionality also relies upon its strong shadows and graded colouration. On the other hand in Chocolate grinder number 2, the object is depicted in what could be described as a conceptual landscape: a neutral and shadow free environment of flat colour and a strict one point perspective. Despite his fascination with the diagram Duchamp continued to seek out new ways to subvert this mechanical, ‘anti-expressive’ system of geometrical depiction on a number of levels, such as his attempts to incorporate chance and chaos in to his artistic process. In "Three standard stoppages", the artist claims to have dropped metre long pieces of string from a height of one metre and traced the outline they made upon landing. These shapes were then cut out of strips of wood and presented in a box as a set of alternative, two dimensional standard metre lengths.

Figure 4: Marcel Duchamp, 3 stoppages étalon (3 Standard Stoppages),

1913–4, replica 1964, Wood, glass and paint on canas, 400 x 1300 x 900 mm

Asked what he considered to be his most important work, Duchamp replied that "As far as date is concerned I'd say the Three Stoppages of 1913. That was when I really tapped the mainspring of my future. In itself it was not an important work of art, but for me it opened the way - the way to escape from those traditional methods of expression long associated with art … For me the Three Stoppages was a first gesture liberating me from the past.' (5)

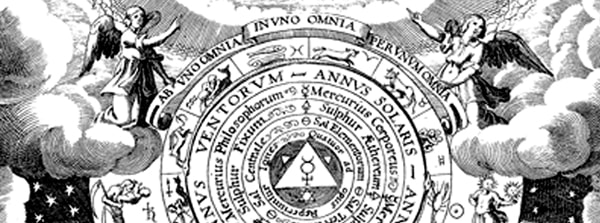

It is important to take into account what was happening within the world of science at the time these works were being made, and Duchamp's active interest in the popular science books of the time. In "Science and Hypothesis" (1902) for example, the mathematician, theoretical physicist, engineer, and philosopher of science Henri Poincaré posed the question of whether or not it would be 'unreasonable to inquire whether the metric system is true or false?'. At almost the same time, two other noteworthy figures Hermann Minkowskiand Albert Einstein were already setting about redefining our most basic understanding of the very geometric fabric of reality for the first time in well over 2000 years. (6) Also of special interest to Duchamp at that time was the work of the French humorist Alfred Jarry (1873-1907), creator of Pataphysics, or the 'science of imaginary solutions'. Jarry developed this imaginary subject to "examine the laws governing exceptions, and … explain the universe parallel to this one", and it is easy to see how Duchamp was drawn to such a novel, humorous and profoundly revealing idea with its suggestions of alternative realities with their own physical laws. (7) The wooden templates of Duchamp's "diminished metres" were later used to design the pattern of lines in his painting "Network of Stoppages" (Reseaux des stoppages), shown below.

Figure 5: Marcel Duchamp, Network of stoppages (Reseaux des stoppages),

1914, oil and pencil on canvas, 198 x 149 cm

The networks are depicted on top of what appears to be a replication of Duchamp's earlier painting "Young Man and Girl in Spring", oil on canvas, 1911, albeit rotated through ninety degrees. This is a subtle contrast of cold chance diagrammatically visualised against the image of a symbolic fertility rite or creation myth.

The large glass subverts the dry, mechanical visual language of objectivity by applying it to subjects that it wasn't designed to address, namely the psycho-sociology of human courtship and sexuality, or what would previously have been called romanticism. [Due to the complexity and art-historical importance of The Large Glass and its accompanying notes, it will be covered in a future post dedicated to that work alone.]

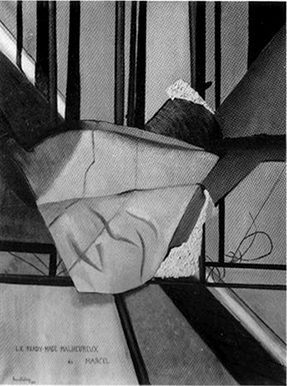

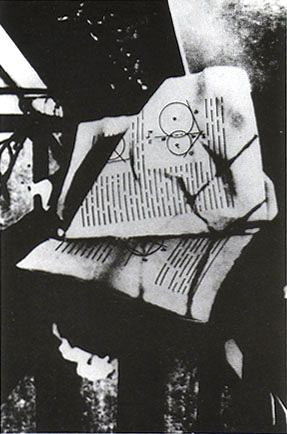

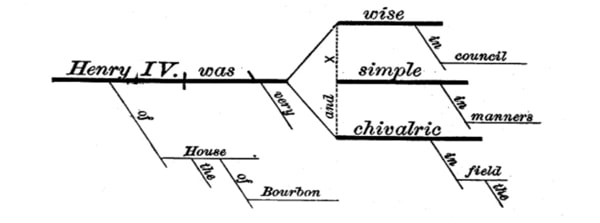

An often overlooked work that questions our notions of ideal forms in geometry with a poetic pathos is Unhappy Readymade, a so called 'assisted readymade' created by Duchamp around 1919 (See figures below).

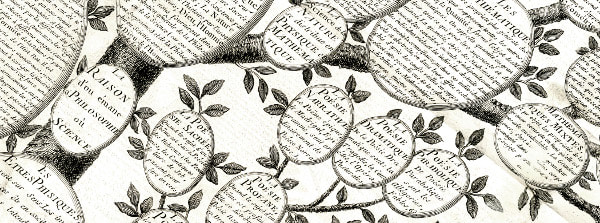

Foreshadowing the production processes of Sol LeWitt, Unhappy Readymade consisted of a simple set of instructions sent by post as a wedding gift to his sister Suzanne Duchamp and the artist Jean Crotti, so that, in the words of LeWitt, “the Idea becomes a machine that makes the art.” (8) In an interview with Pierre Cabanne, Duchamp described his instructions for Crotti to buy a "…geometry book which he had to hang by strings on the balcony of his apartment in the rue Condamine; the wind had to go through the book, choose its own problems, turn and tear out the pages. Suzanne did a small painting of it, ‘Marcel’s Unhappy Readymade.’ That’s all that’s left, since the wind tore it up. It amused me to bring the idea of happy and unhappy into readymades, and then the rain, the wind, the pages flying, it was an amusing idea… " (9)

Duchamp’s unhappy readymade sets out to highlight the contrast between ideal geometric forms which exist only as concepts, their manifestation as token textbook diagrams of ink on paper and the results of weathering on the text book.

The Duchamp scholar Linda Dalrymple Henderson points out that this was in fact one of the artist's last specific comments on geometry, and that the book used was a copy of Euclid’s elements so that, ironically, the plane geometry of Euclid was in contrast to damage caused by the wind and rain producing distortions in the diagrams as “non-Euclidean deformations of the Euclidean geometries in the text.” (10) In a letter to his sister, Duchamp wrote: “I liked the photo very much of the Ready Made sitting there on the balcony. When it all falls apart you can replace it.” (11) Duchamp also suggests that this is a lesson to be repeated, a reminder of the fundamental difference between an essentialised, idealised, conceptual landscape of perfect forms, and the chaotic nature of decay and change, which composes our everyday experience of the real world. Some years later Duchamp told one interviewer that “he had liked disparaging ‘the seriousness of a book full of principles,’ and suggested to another that, in its exposure to the weather, ‘the treatise seriously got the facts of life’”. (12)

Below is a scanned reproduction of the British, Victorian mathematician Oliver Byrne's 1847 edition of Euclid's Elements. Created almost a century before the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian made geometrical red, yellow, and blue lines so famous, Byrne titled his edition "The First Six Books of the Elements of Euclid in Which Coloured Diagrams and Symbols Are Used Instead of Letters for the Greater Ease of Learners".

Downloadable copies are available in various formats courtesy of an Internet Archive at the University of Toronto Libraries here: Downloadable formats Or as a pdf here: Downloadable pdf. Click on the pages of the book below to turn them: Oliver Byrne (1810–1890) was a civil engineer and prolific author of works on subjects including mathematics, geometry, and engineering. His most well known book was this version of ‘Euclid’s Elements’, published by Pickering in 1847, which used coloured graphic explanations of each geometric principle. The book has become the subject of renewed interest in recent years for its innovative graphic conception and its style which prefigures the modernist experiments of the Bauhaus and De Stijl movements. Information design writer Edward Tufte refers to the book in his work on graphic design and McLean in his Victorian book design of 1963. In 2010 Taschen republished the work in a wonderful facsimile edition. ( Wikipedia link )

References:

1) Nayral, J. (1912) preface to Galeries J. Dalmau, Barcelona. Exposció de Arta cubista. (April – May 1912) Reprinted in Guillaume Apollinaire: Les Painters Cubistes. Breunig, L.C., Chevaliare J. Cl. Paris: Hermann (1965) p. 181 2) Nesbit, M. (1991) The Language of Industry. In: The Definitely Unfinished Marcel Duchamp. De Duve, T. (Ed.) Massachusetts: Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1991. pg.356. 3) Duchamp, M. Salt Seller: The writings of Marcel Duchamp (Marchand du sel). Eds. Sanouillet, M. Peterson, E. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973. p. 30. 4) Duchamp, M. As quoted in Sweeney, A conversation with Marcel Duchamp, NBC Television interview, January 1956. Sweeney, J.J. (1946) Eleven Europeans in America: Marcel Duchamp. Museum of Modern Art Bulletin 13, p. 19-21. In: Dalrymple Henderson, L. (1998) Duchamp in context: Science and technology in the large glass and related works. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 5) Duchamp, quoted in: Katherine Kuh, The Artist's Voice: Talks with Seventeen Artists, New York 1962, p.81. 6) Henri Poincaré quoted in: Herbert Molderings, 'Objects of Modern Scepticism', in Thierry de Duve (ed.), The Definitively Unfinished Marcel Duchamp, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1991, pp.243-65, reproduced p.247 Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, revised and expanded edition, New York 1997, pp.594-6, reproduced pp.594, 595, 596 7) Alfred Jarry quoted in: Dawn Ades, Neil Cox and David Hopkins, Marcel Duchamp, London 1999, pp.78-9, reproduced p.78 8) LeWitt, S. (1967) Paragraphs on Conceptual Art. Art Forum. June, 1967 9) Cabanne, P. (1971) Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp. Originally published: London: Thames and Hudson. p. 61. 10) Dalrymple Henderson, L. (2013) The Fourth Dimension and non-Euclidean geometry in Modern Art. 2nd Revised Edition. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. p. 283. 11) Duchamp, M. (1920) Letter to Suzanne Duchamp. In: Affectueusement, Marcel: Ten Letters from Marcel Duchamp to Suzanne Duchamp and Jean Crotti. (1982) Francis Naumann, M. Archives of American Art Journal, Vol. 22, No. 4. pp. 2-19. 12) Tompkins, C. (1998) Duchamp: A Biography. New York: Henry Holt and Co. Inc. p.212-214 ❉ This is the second in a series of blogs that discuss diagrams in the arts and sciences. I recently completed my PhD on this subject at Kyoto city University of the Arts, Japan's oldest Art School. Feel free to leave comments or to contact me directly if you'd like any more information on life as an artist in Japan, what a PhD in Fine Art involves, applying for the Japanese Government Monbusho Scholarship program (MEXT), or to talk about diagrams and diagrammatic art in general.

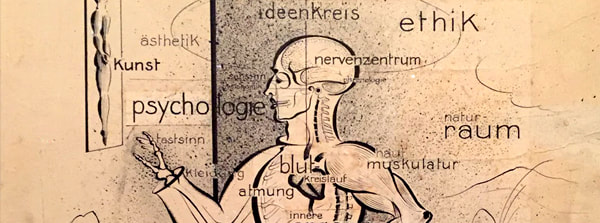

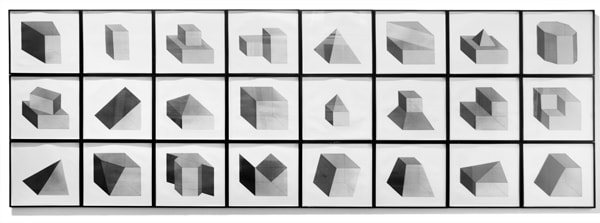

What would happen if you were to change the focus of an entire country's art education system from imitating nature and the human body to mastering the art of technical drawing and creating diagrams ? By the time the French artist Marcel Duchamp was born in 1887, the French national education system had undergone a systematic overhaul and just such changes were already in place in the art departments of each state funded public school. (1) Students of art were no longer expected to study and mimic classical sculpture, the old masters, or the art of the renaissance. Instead, the aim of the new curriculum was fluency in a measured, mechanical drawing style that was refined, skeletal and precise. Referred to as the 'language of industry', this was a whole-sale promotion of a new national, visual language of science, technology and culture in the age of mechanical production. In other words, second only to the epic encyclopedic projects of the 1700's, this was the new dawn of the diagram at the heart of French Culture. In her essay titled 'The language of Industry', Molly Nesbit describes how "by and large this was a language meant for work, not for leisure, and certainly not for raptures or poetic, high cultural sighs. This language was pre-aesthetic, a public culture based upon mechanical drawings, sans colour, sans nature, sans body, sans the classics, some would have said sans everything." (2) Within the class rooms, drawing courses were divided in to depicting objects in perspective (objects reproduced the way they appear to the eye) and in projection (objects depicted as ideal forms, independent of a human observer and the optics of our two human eyes). Because of this distinction, French art students were taught to make a fundamental distinction between apparent and true representation, just as Duchamp himself would later make a similar distinction between what he called retinal and non-retinal art.

Marcel Duchamp went on to develop his artistic use of diagrams and diagramming in a number of important ways, from the one dimensional plumb lines that he dropped to make '3 standard stoppages' (a work which questions the one dimensional meter as a standard unit of length), to his intricate two dimensional sketches for 'The Large Glass' which suggest archetypal lines and platonic skeletal forms in higher dimensions.

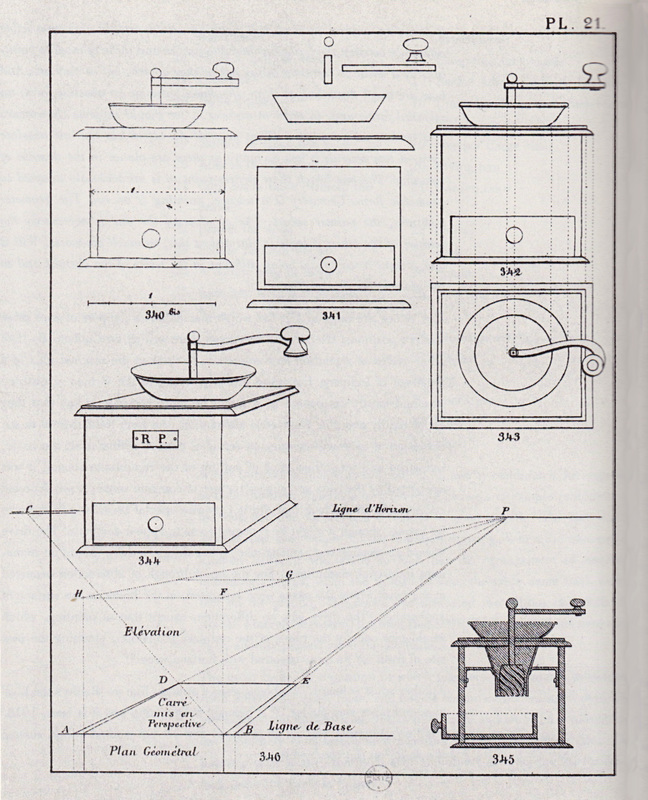

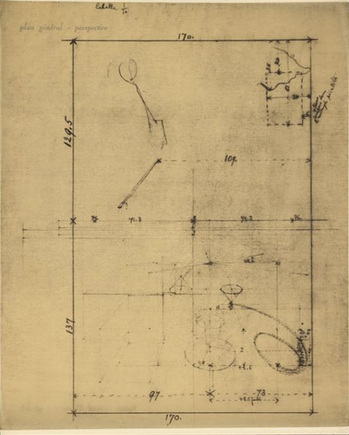

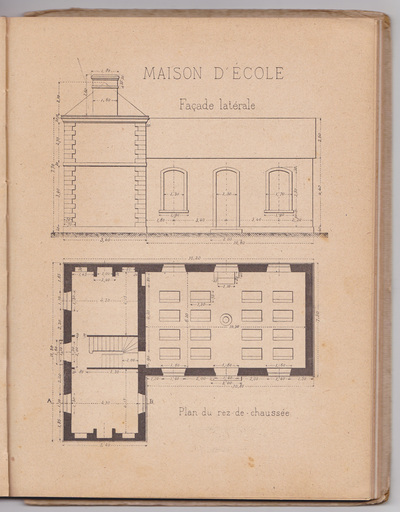

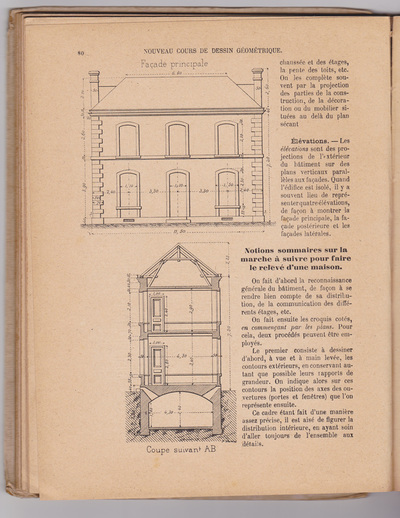

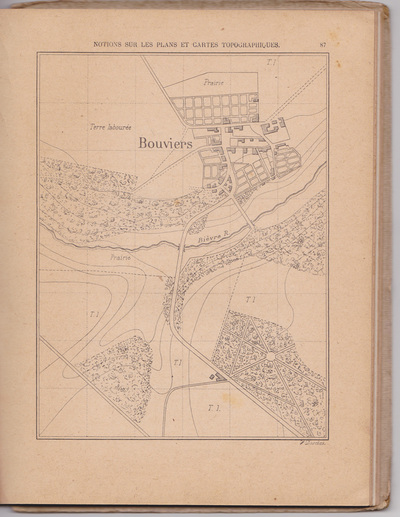

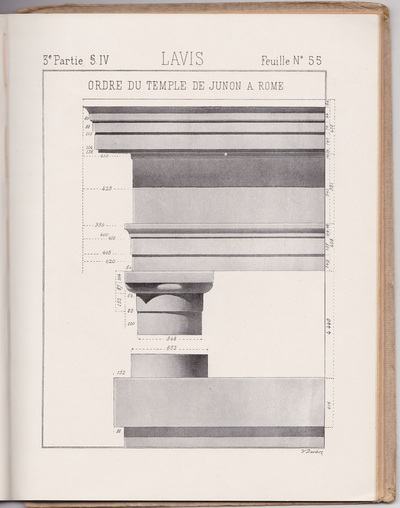

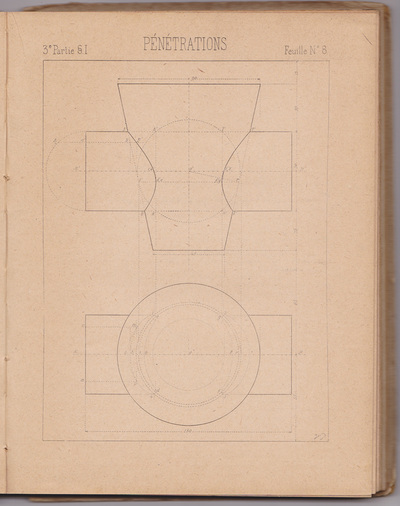

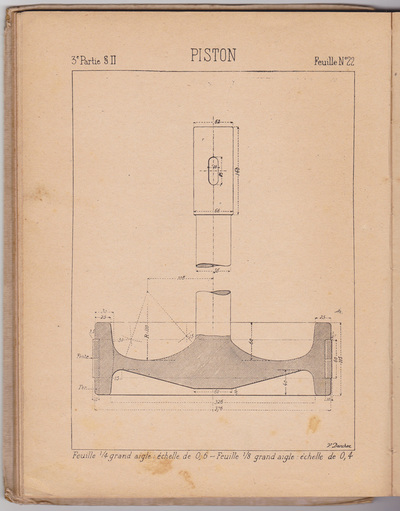

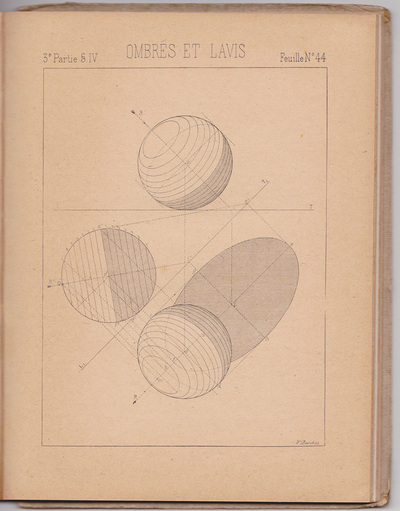

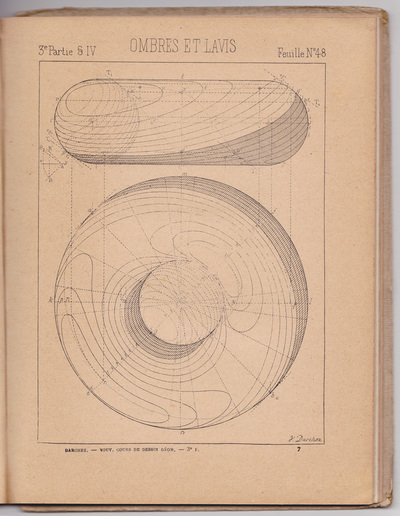

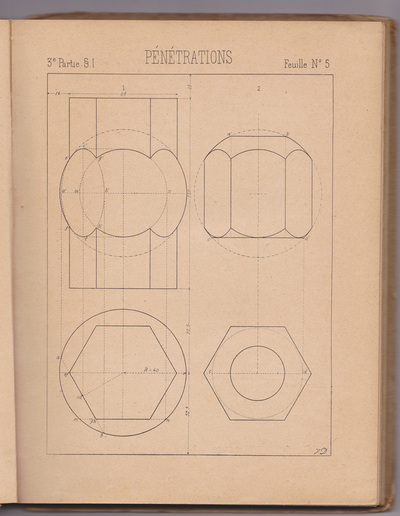

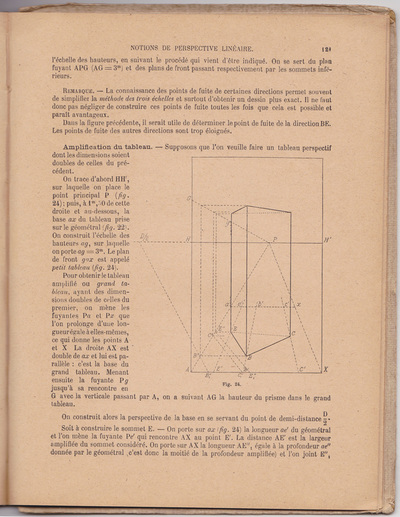

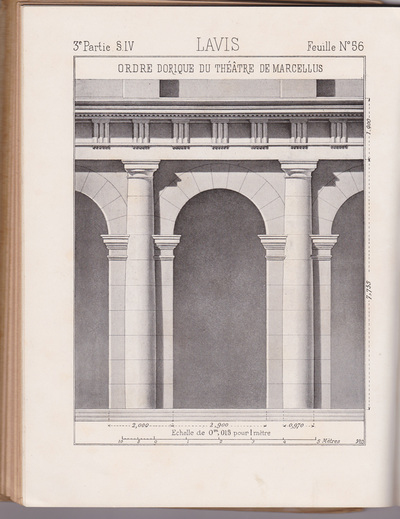

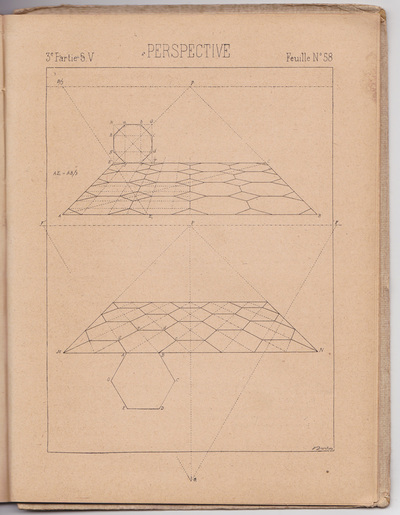

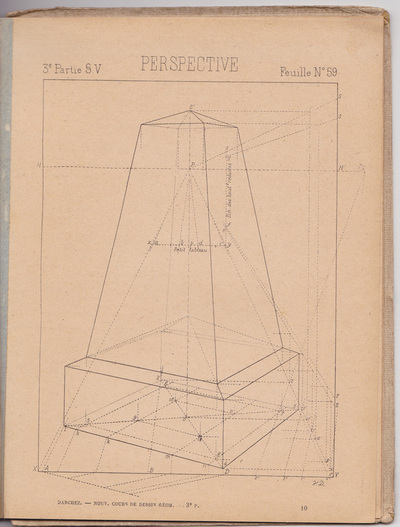

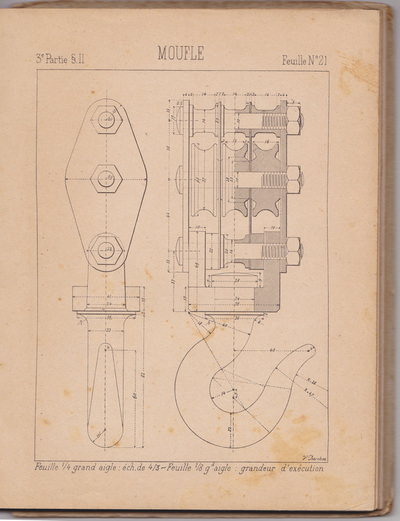

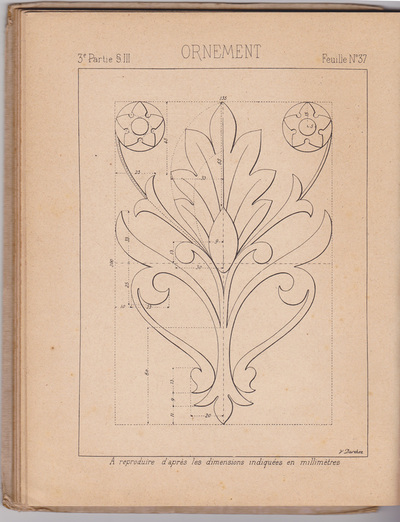

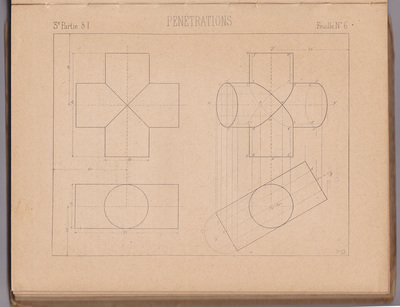

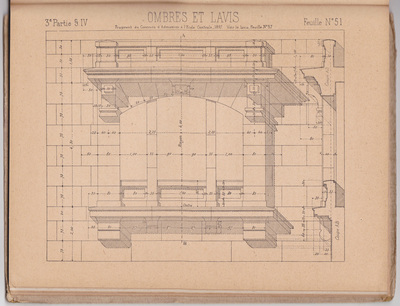

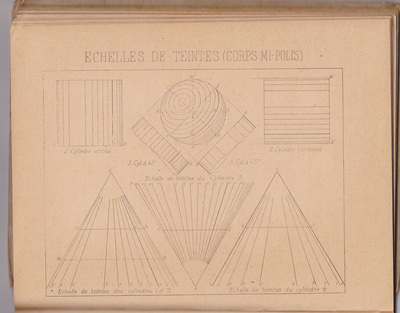

Duchamp's various projects embodied a more general shift in science and culture, from drawing as a representation of the natural world, to drawing as a means of depicting the technical nature of the structural and functional systems which underlie reality, as described by science and mathematics, but always by means of the diagram. The following diagrams were scanned from the third book in the series "Nouveau Cours de Dessin géométrique", compiled by Professor V. darchez of the state-funded secondary school in Lyon. The director of the Beaux-Arts School in Paris at the time, the sculptor and critic Eugène Guillaume, elaborated upon the new program of diagrammatic training: "Drawing is by its very nature exact, scientific, authoritative. It images with undeniable precision (to which one must submit) things such as they are or as they appear. Not one of its configurations could not be analyzed, verified, transmitted, understood, realized. In its geometrical sense, as in perspective, drawing is written and is read: it has the character of a universal language." (6) References:

1) The 'Ferry Reforms' of the French national school system were established during the 1870s and 80s. 2) Nesbit, M. The Language of industry (1991). In: The Definitely unfinished Marcel Duchamp, MIT Press, 1991, p.356. 3) Duchamp, M. interview with Dorothy Norman, first published in Art in America, Vol.57, July -Aug. 1969. p38. 4) Duchamp, M. In: Schwarz, A. The Complete works of Marcel Duchamp, revised and expanded edition, New York, 1997, p.573. 5) Duchamp, M. In; Ades, D., Cox, N., Hopkins, D. Marcel Duchamp, london, 1999, p.75. 6) Nesbit, M. The Language of industry (1991). In: The Definitely unfinished Marcel Duchamp, MIT Press, 1991, p.372. |

Dr. Michael WhittleBritish artist and Posts:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|