|

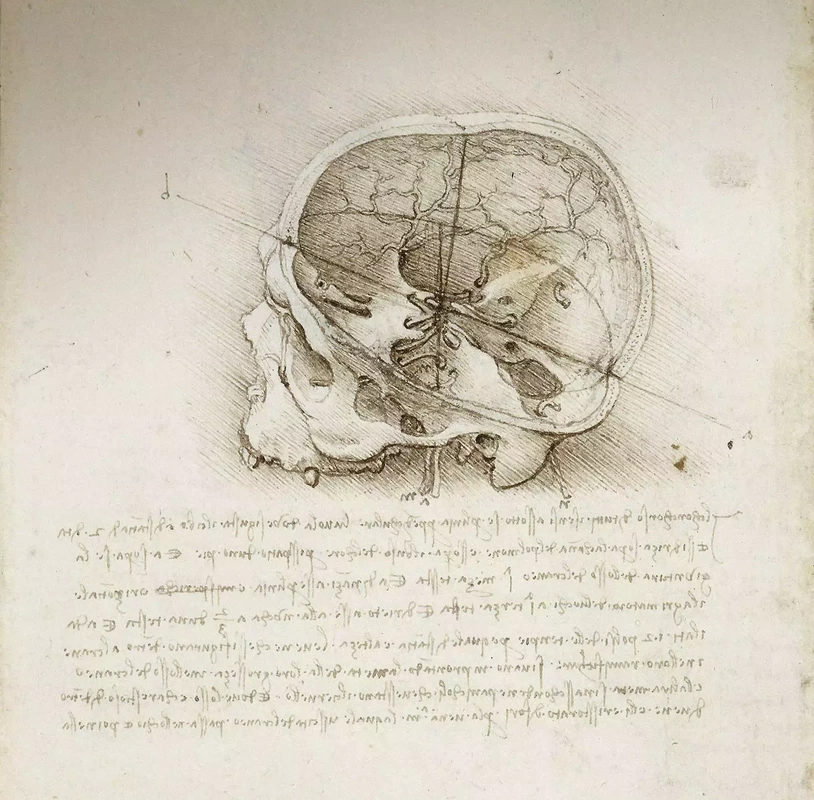

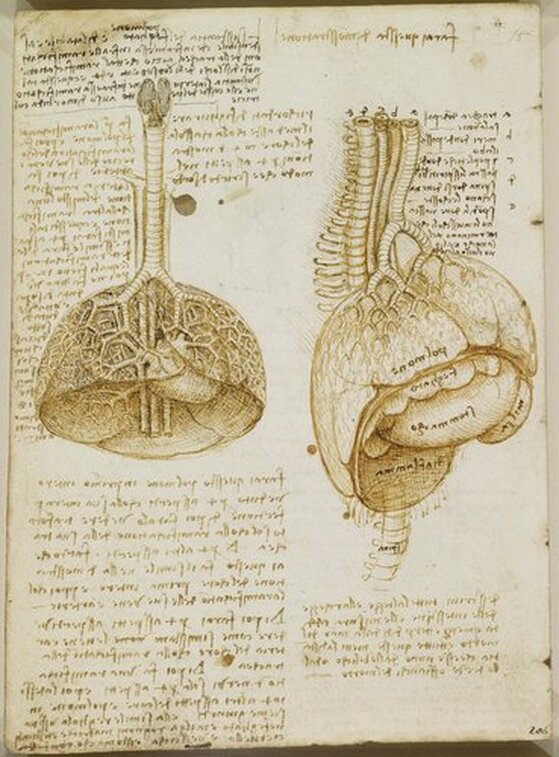

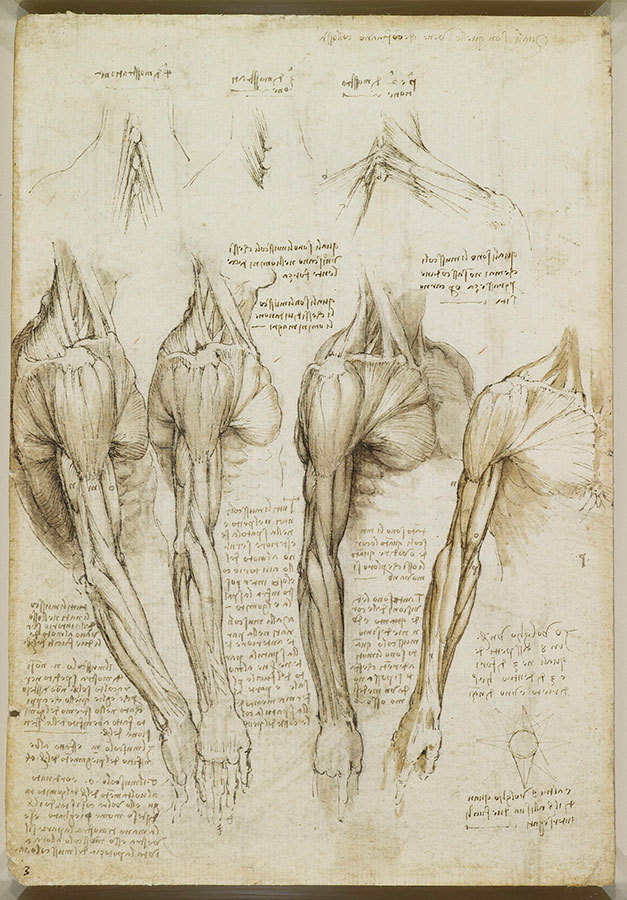

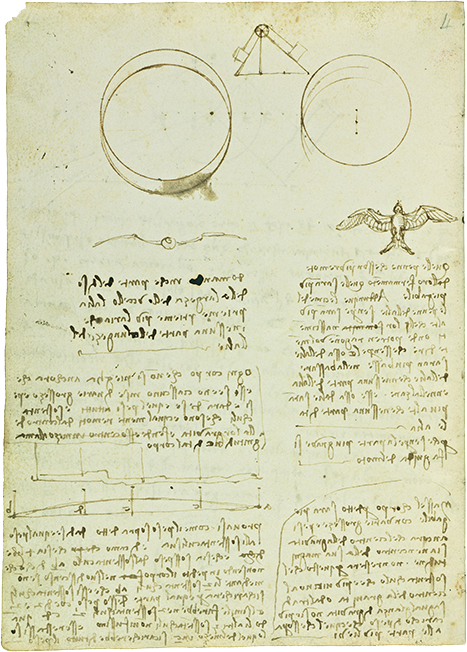

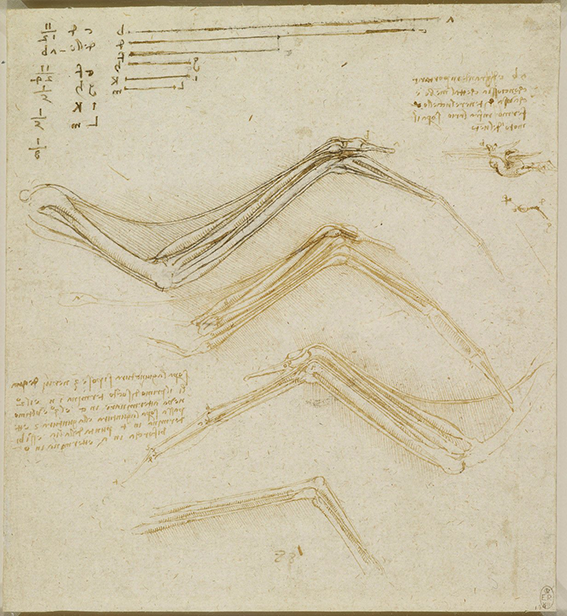

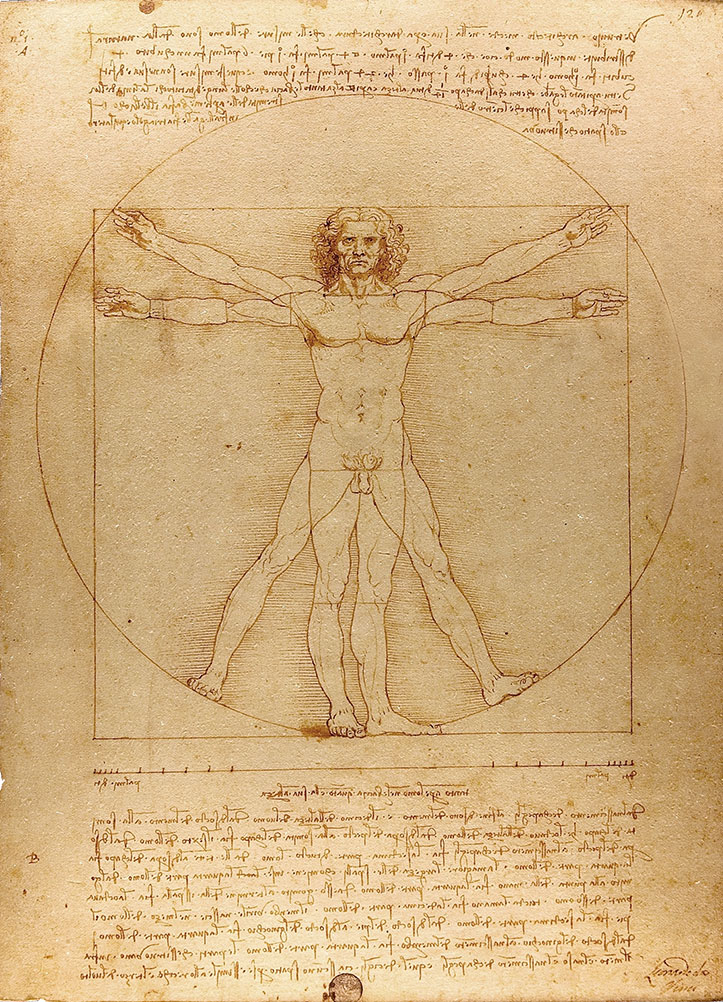

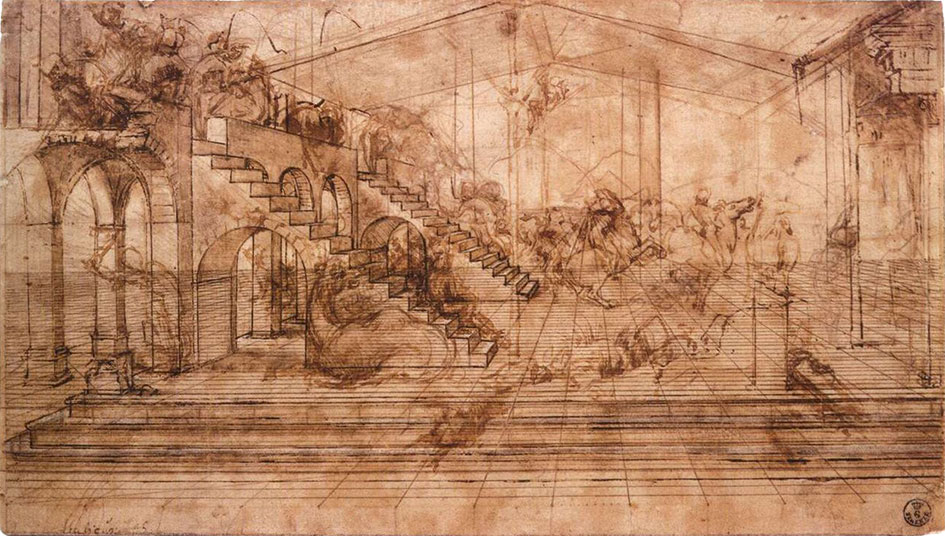

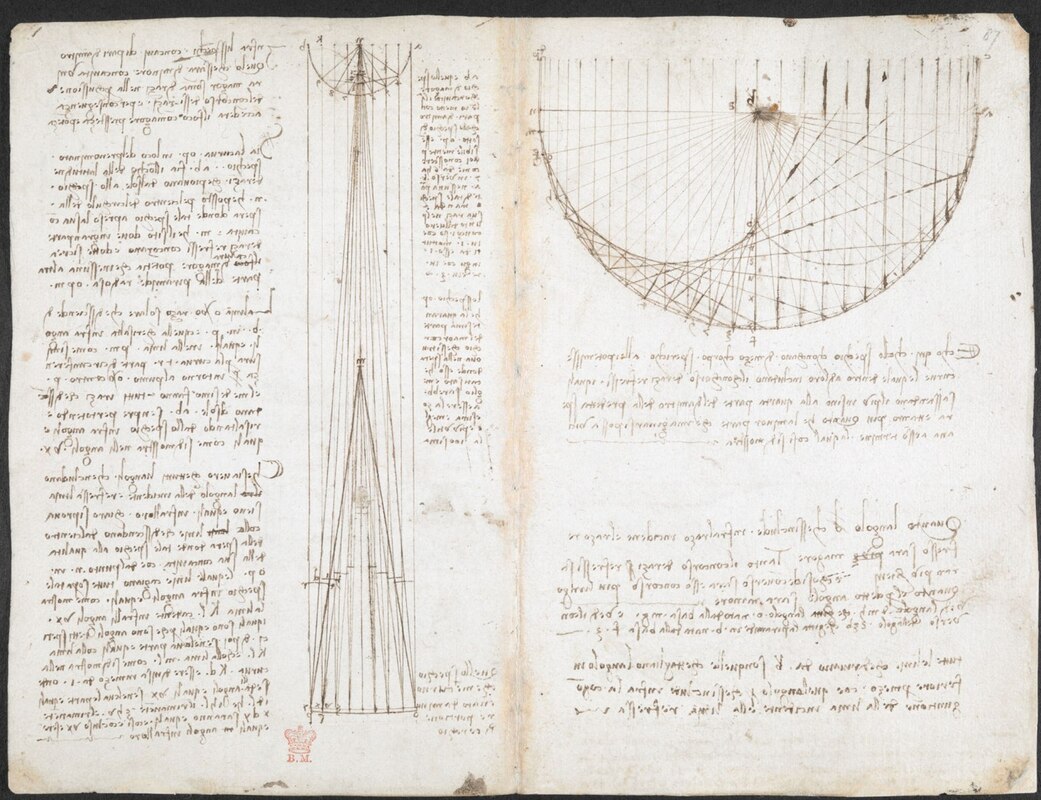

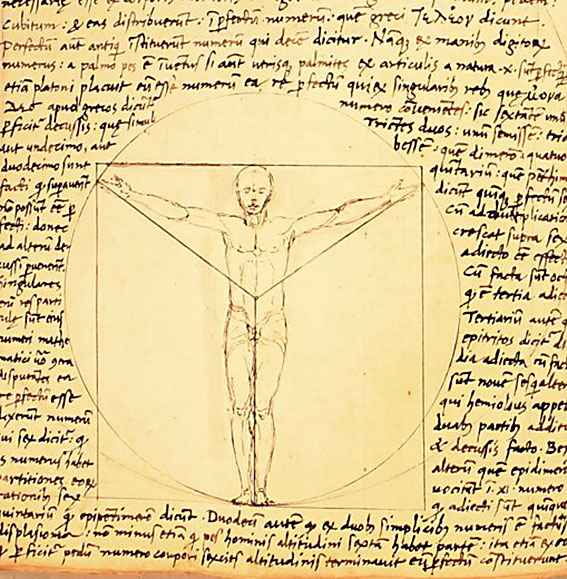

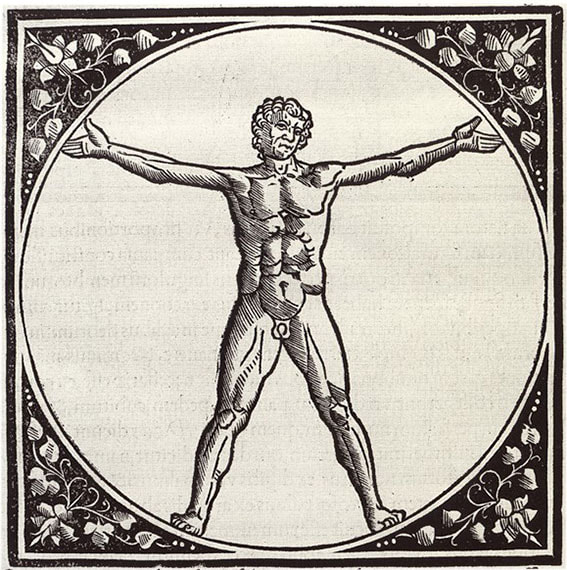

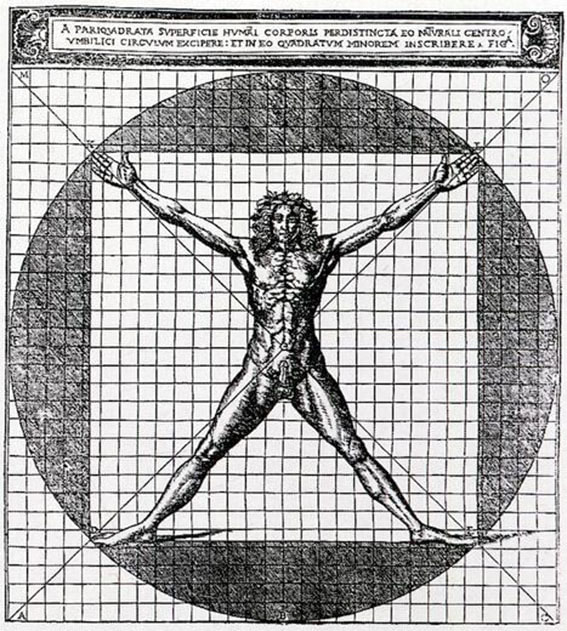

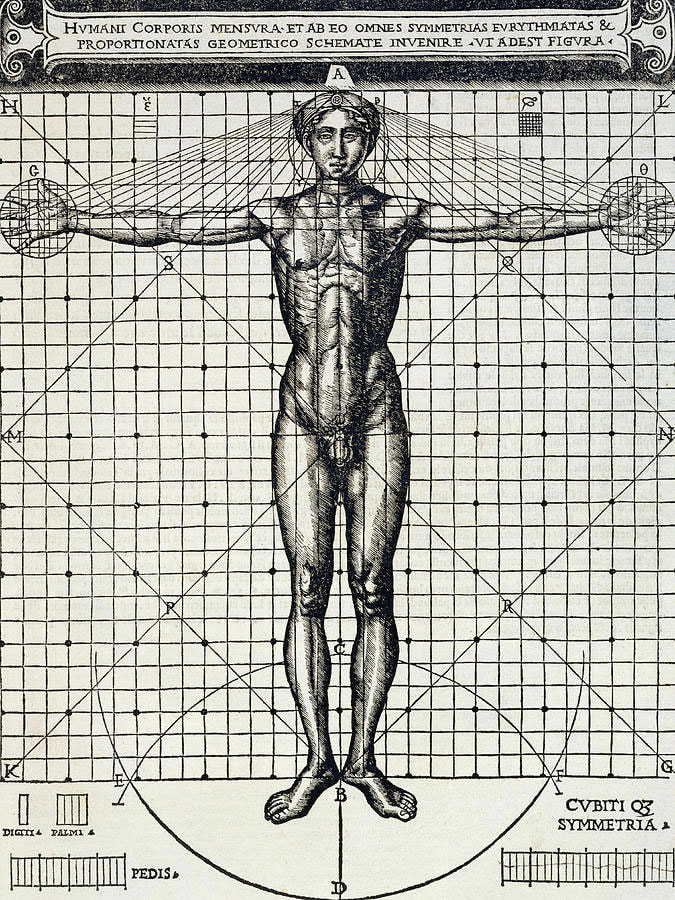

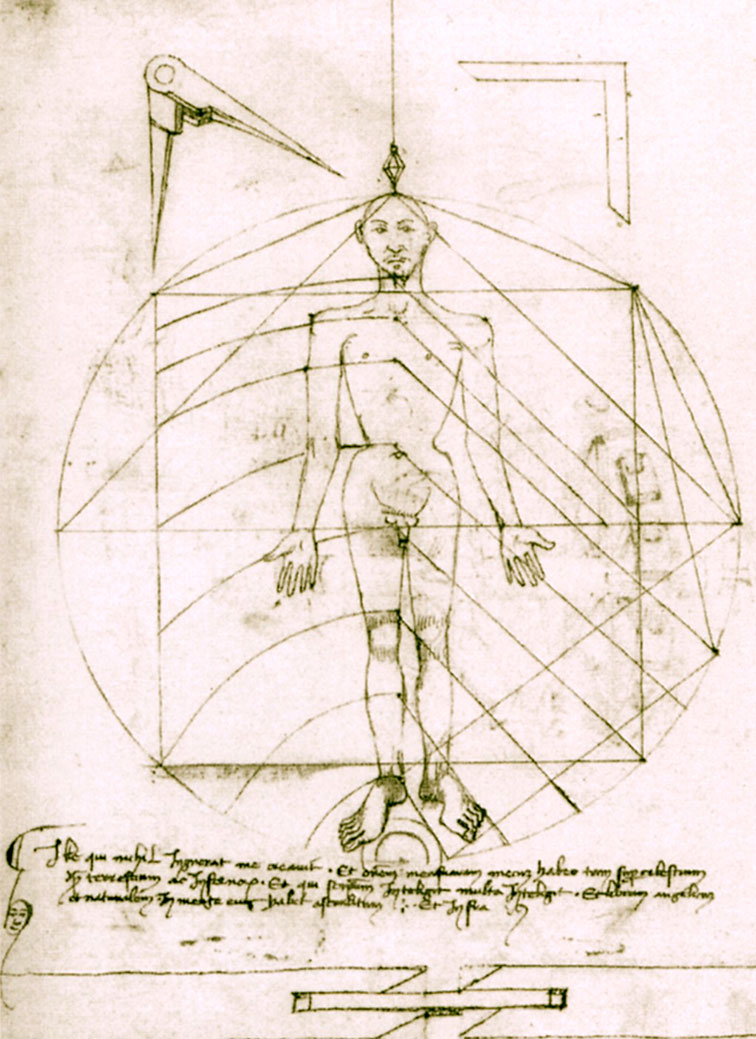

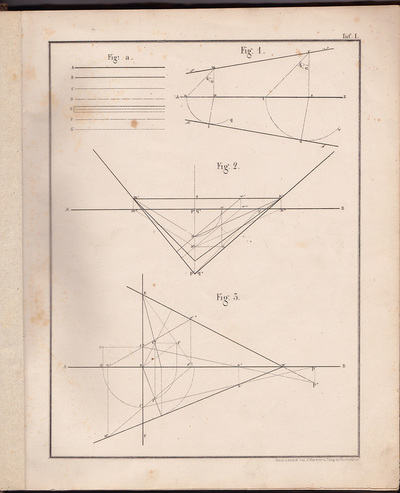

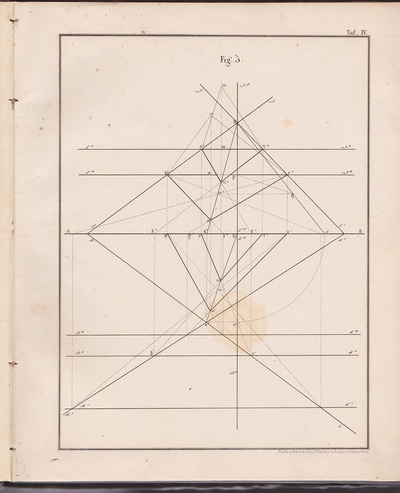

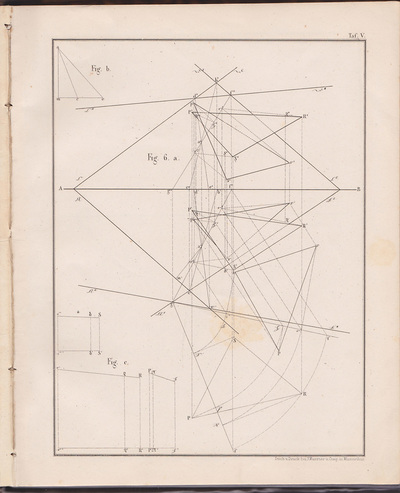

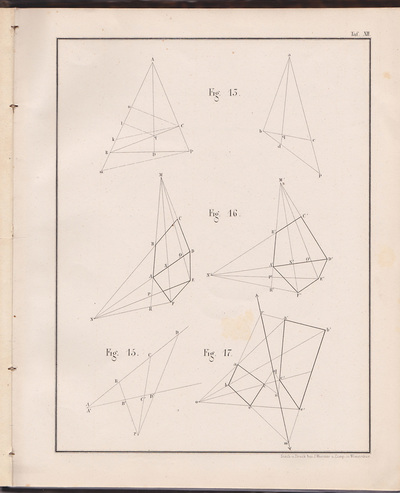

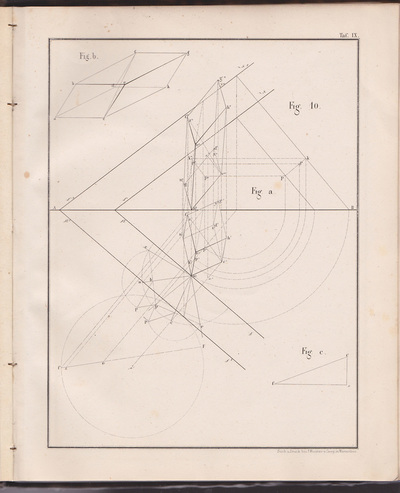

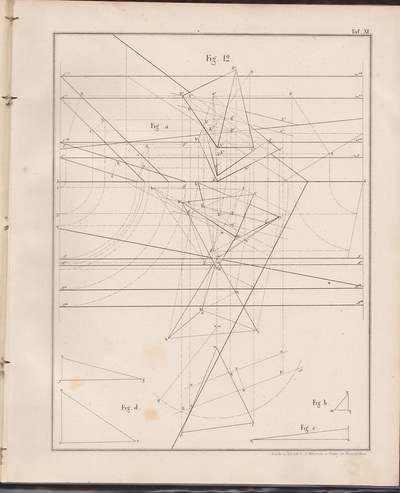

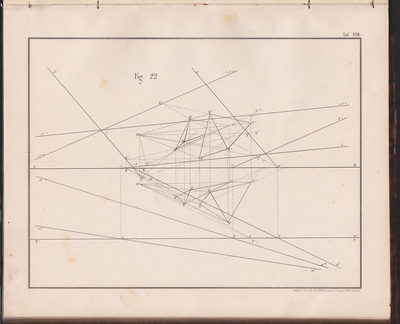

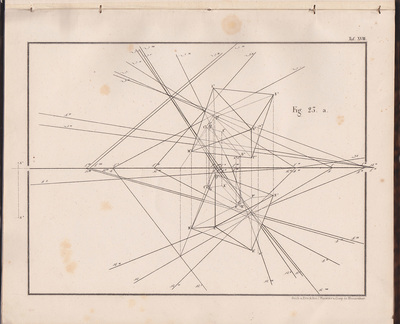

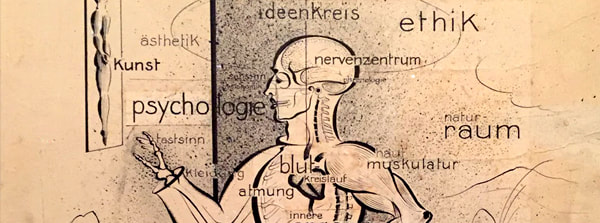

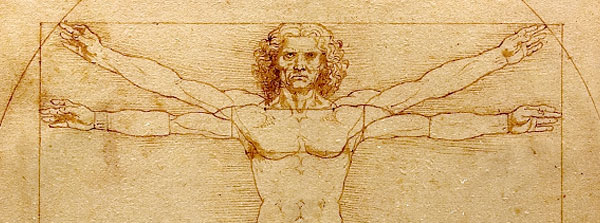

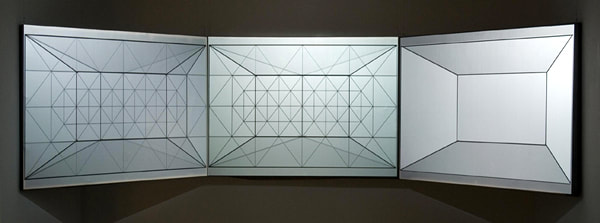

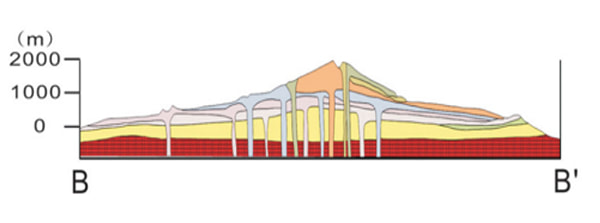

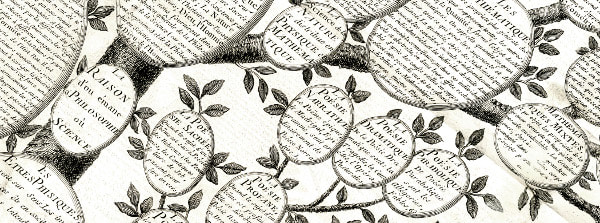

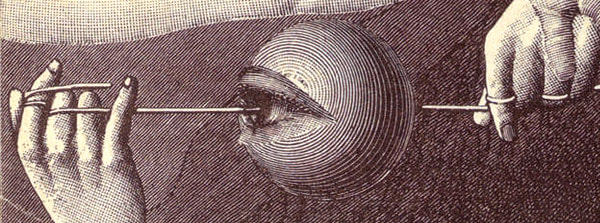

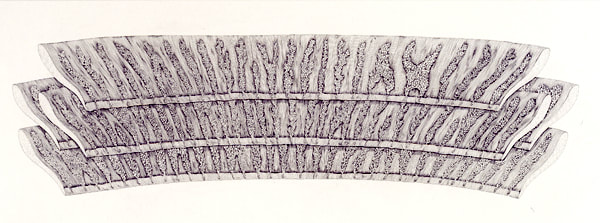

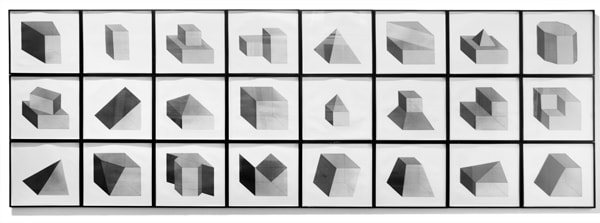

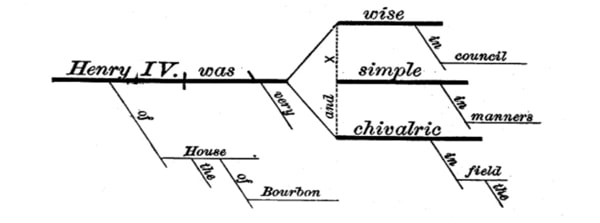

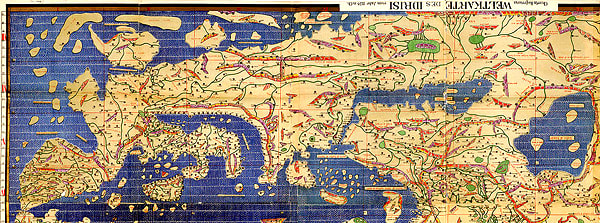

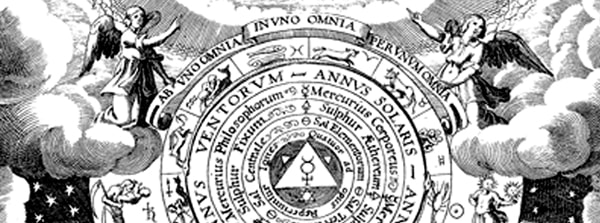

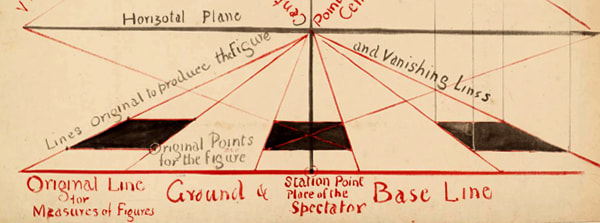

❉ Blog post 20 on diagrams in the arts and sciences delves in to Leonardo Da Vinci's life long obsession with diagram making. From documenting ideas and observations, to elaborate mechanical instructions, blueprints for buildings and sketches for paintings, the diagram was the creative engine that drove his endless pursuit of knowledge and understanding. 1) Glimpse into the left side of a human skull, about 1651 © Royal Collection Trust / Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) The surviving notebooks of early Renaissance artist and polymath Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) reveal a masterful fluency in his use of diagrams. Indeed, during certain periods, his distinctive mirror-written notes and diagrammatic sketches were his medium of choice for observing and analysing the world, rather than drawing and painting. However as we'll see, all of these modes of exploration and expression were intimately connected, especially so in the case of his complex preparatory diagrams that underlie some of his major paintings. Geometry was fundamental to Leonardo’s process of understanding both the visible forms of nature and the hidden mechanisms and forces underlying natural phenomena. His vision of the interplay of these rules of geometry was transformative and dynamic rather than static, as if he observed nature as a process of geometry in action. He was however not merely content to record how something worked, but also strove to find out why it worked the way it did, and it was this insatiable curiosity that transformed a technician into a scientist. (1) In the words of the great da Vinci scholar Martin Kemp, for Leonardo, the "...muscles of the human body worked immaculately according to the laws that governed levers. The flow of the blood in the vessels and of the air in the bronchial tubes in the lungs was governed by the geometrical rules that applied to all branching systems. A flying bird was designed in perfect conformity with the geometry of airflow.” (2) (See figures 2-5) Leonardo studied anatomy and the proportions of the human body throughout his career, and applied this deep understanding in drawings such as The Vitruvian Man (c.1490) (figure 6). This diagrammatic sketch was Leonardo's attempt to answer an ancient puzzle set 1500 before his time by the first century Roman architect and engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (c. 75–25 BCE). In his book De Architectura, Vitruvius founds his theory of architecture on the proportions of the human body, which he considered nature’s greatest work. The challenge was to show how the human figure can be positioned within a circle and a square with the navel at the centre. Ancient thinkers had long invested the circle and the square with symbolic powers, with the circle representing the cosmic and the divine, and the square the earthly and the secular. Leonardo's elegant solution was to position his figure so that the navel aligned with the centre of the circle, but then to position the square off-centre in alignment with the base of the circle. (figure 6) 6) The Vitruvian Man, c. 1490 Pen and ink with wash over metalpoint on paper, 34.6 cm × 25.5 cm Interestingly, a number of other artists from around the same period also attempted solutions to the Vitruvian puzzle, and some comparative examples are included below that highlight the refined technical elegance of Leonardo's draftsmanship and his exceptional knowledge of anatomy. One drawing in particular, made by Leonardo's close friend Giacomo Andrea Da Ferrara, actually predates that of Leonardo's, and its rediscovery in a lost manuscript in Ferrara, Italy in 1986, lead some art historians to question whether or not Leonardo's drawing was actually of copy of his friend's solution. (3) (See figure 9) 7) Perspective study for the adoration of the Magi, c. 1481 Ink on paper, 16.3 x 29 cm, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi Leonardo’s preparatory study for the adoration of the Magi is one of his most remarkable sketches. (figure 7) The immaculately depicted geometry of the tiled floor and the static architecture of the temple interior highlight the turbulent graphic images of the figures and animals depicted within it. British art historian Kenneth Clark described the drawing as "a carefully measured courtyard invaded by a retinue of ghosts". Clark considered it one of Leonardo's most revealing drawings, and the earliest evidence of his scientific attainments in perspective, which to his mind provided "a scaffold for the artist's imagination." (4) Likewise, Martin Kemp considers the sketch an exemplar of the paradoxical combination of contained measure and unconstrained improvisation characteristic of many of Leonardo’s drawings. (5) The reduction of complex natural forms to their underlying geometrical relations was, however, more of an intuitive process for Leonardo than one relying upon the techniques of mathematics. Kemp has suggested that this preference may have been two-fold, both in Leonardo’s own limited abilities at mathematics and algebra but also as an intellectual preference for a more fluid model of a dynamic world based on the beauty of proportions, interrelations and first-hand experience of the world. Leonardo referred to geometry as “the science of continuous quantity’” whereas he referred to numbers and mathematics as dealing with “discontinuous quantities” with little correspondence to the nature of actual physical forms. (6) In his essay for the book accompanying the 2006 exhibition 'Leonardo da Vinci: Experience, Experiment and Design' at the Victoria and Albert museum in London, Kemp discusses Leonardo’s use of disegno as a means to think visually. Disegno was a common term used by Renaissance draughtsmen and is normally translated in English as either drawing (in a fine art context) or design (in the context of applied arts). Leonardo’s use of disegno allowed him to integrate the subjective imaginative faculty or fantasia with the intellect, which in turn achieved expression in the Renaissance concept of science (scientia). Misura was the term used to describe the measuring of proportions, the construction of perspective systems and rules of light and shade, and was regarded by Leonardo as the fundamentally scientific aspect of expression in painting. (7) In works such as the Perspective study for the adoration of the Magi (figure 6), we can see this process at work in the way he combines the fluid, creative, subjective process of disegno with the logic, rigor and measurement of misura. Kemp uses the following quote from Leonardo to support his claim that disegno was considered as the supreme tool that served the eye as a means of investigation and exposition. When Leonardo praises how the eye commands the hand, Kemp suggests that he was essentially making claims about the power of disegno: "Now do you not see that the eye embraces the beauty of the world? The eye is commander of astronomy; it makes cosmography; it guides and rectifies all the human arts; it conducts man to various regions of the world; it is the prince of mathematics; it’s sciences are most certain; it has measured the height and size of the stars; it has disclosed the elements and their distributions; it’s made predictions of future events by means of the course of the stars; it has generated architecture, perspective and divine painting. Oh excellent above all other things created by God… And it triumphs over nature, in that the constituent parts of nature are finite, but the works that the eye commands of the hands are infinite." (8) 8) Codex Arundel, circa 1480 - 1518 (See below for a link to a digitised version) However, it's immediately notable that the systems Leonardo is praising, all relate to the power of diagrams, diagramming, and diagrammatic thought processes, and this becomes even clearer if we consider the examples he refers to: astronomy and celestial charts, the theory and practice of the systems of proportions governing artistic beauty, cosmography (9), cartography and navigation, mathematics including trigonometry and geometry, the analysis of dynamic and static systems in the behavior of earth, water, air and fire, architectural plans, elevations, sections and systems of perspective and the ‘divine’ science of painting with its ‘roots in nature’. Drawing and thinking through diagrams was for da Vinci a natural, almost instinctual means to develop his ideas, communicate them with others and construct a science of painting. However, as with other artists of the Renaissance, Leonardo inherited the tradition for diagramming from Medieval diagrammers before him, as I covered in previously blog posts: Diagrams from the Dark Ages, and Cosmic Diagrams from Alchemical Laboratory. Leonardo's online Codex:Leonardo's Codex Arundel consists of 570 images of dense cryptic notes surrounding technical diagrams. The 283 page manuscript was digitized in 2007 as a joint project between the British Library and Microsoft called “Turning the Pages 2.0,” and can be accessed by clicking here. The Alternative Vitruvian Men: |

Dr. Michael WhittleBritish artist and Posts:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|