|

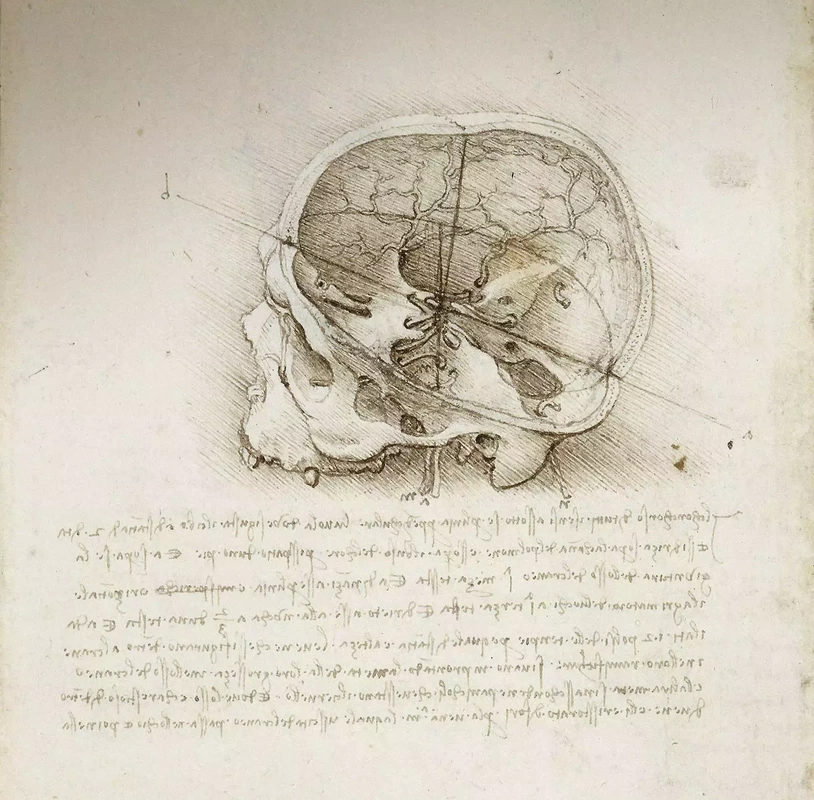

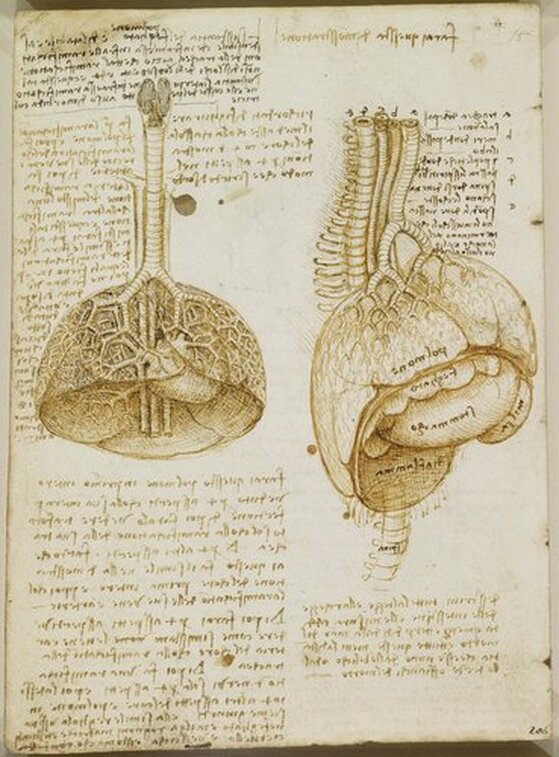

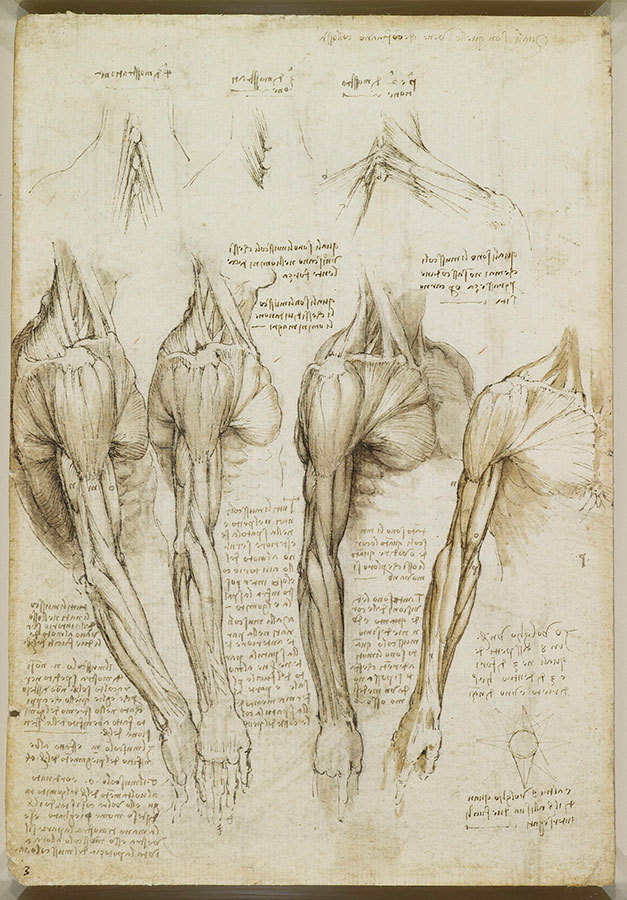

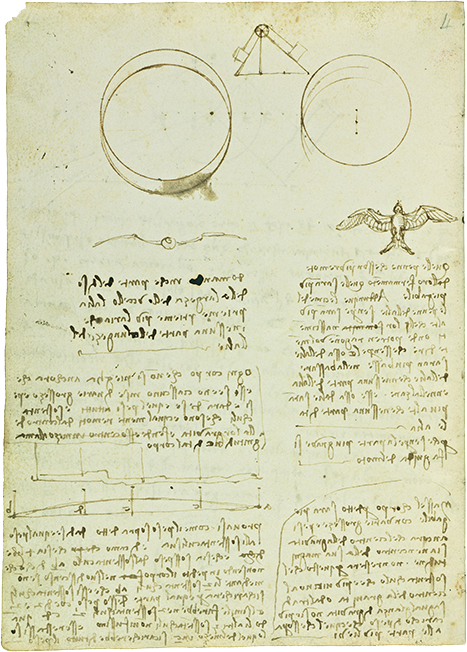

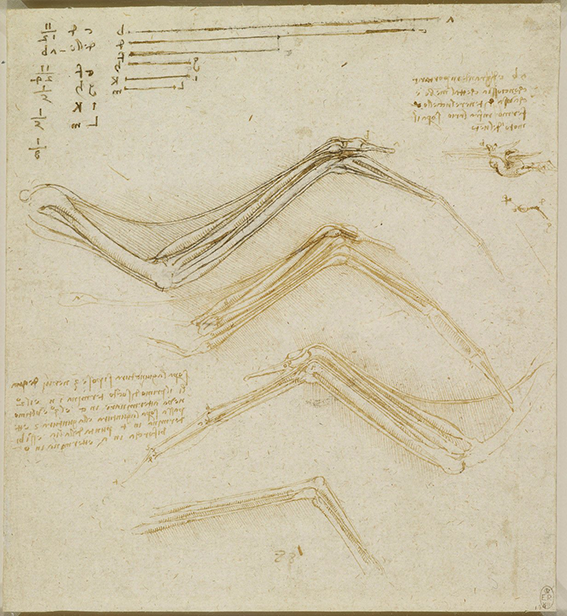

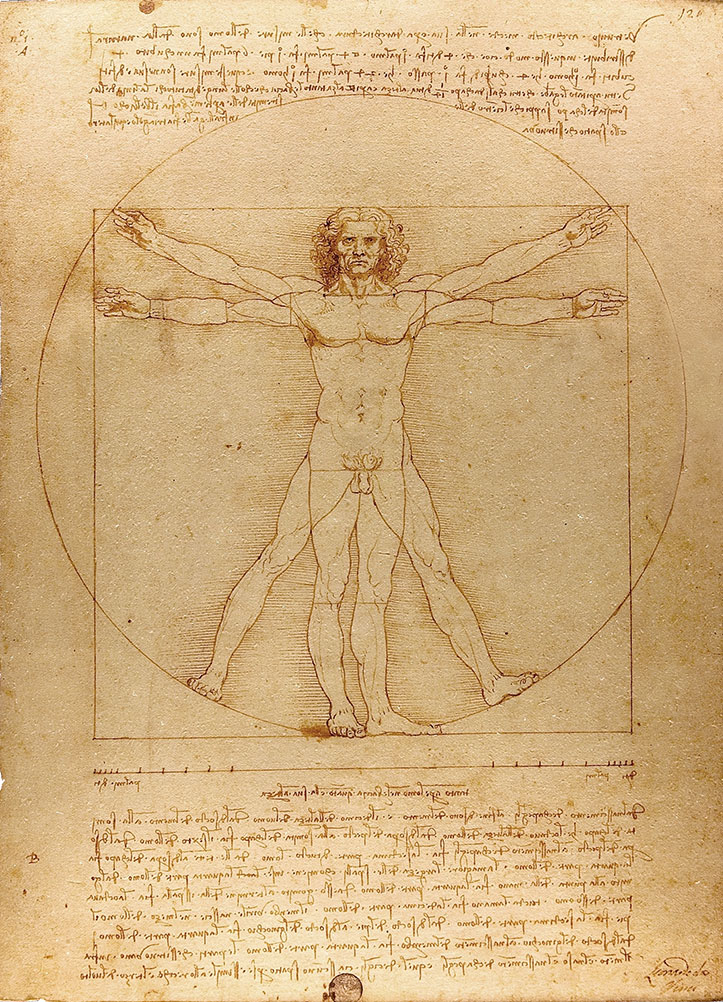

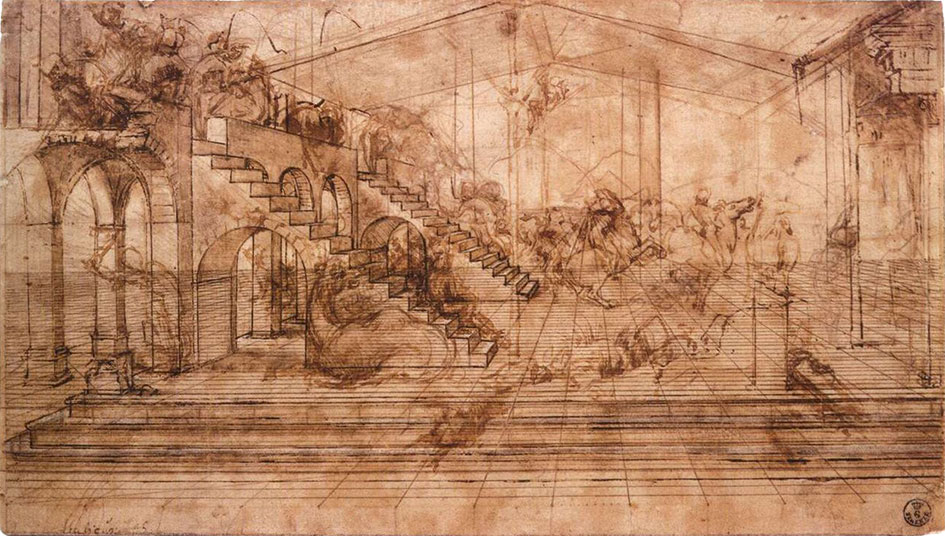

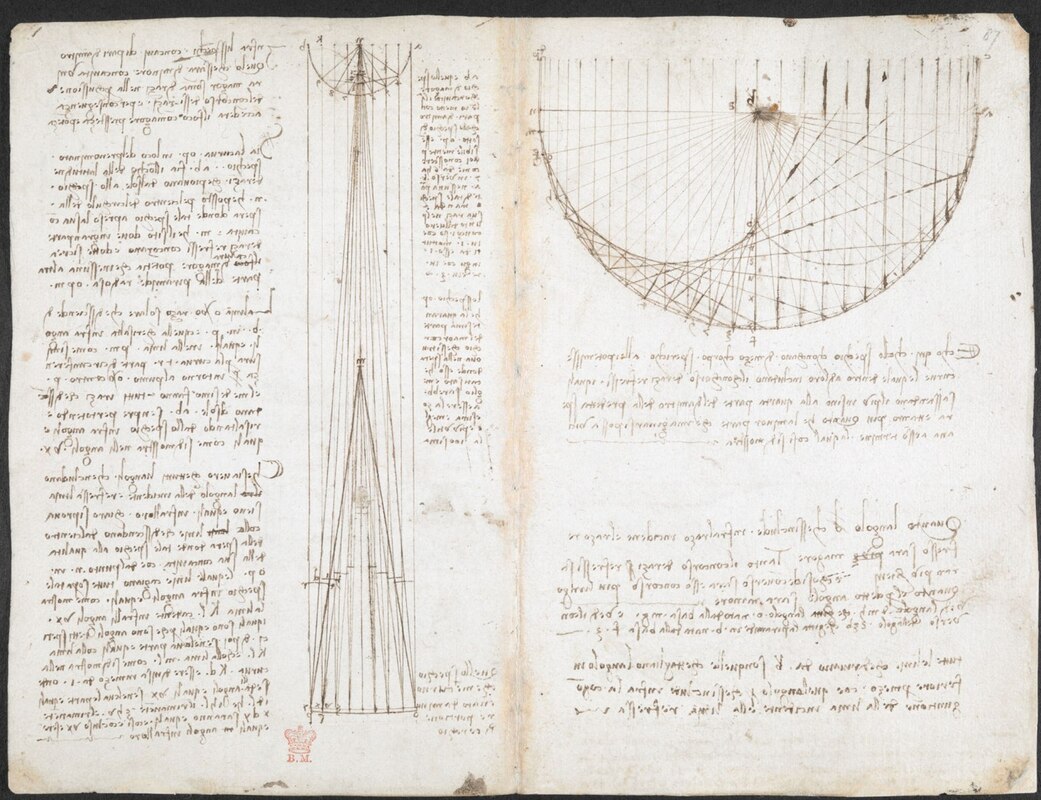

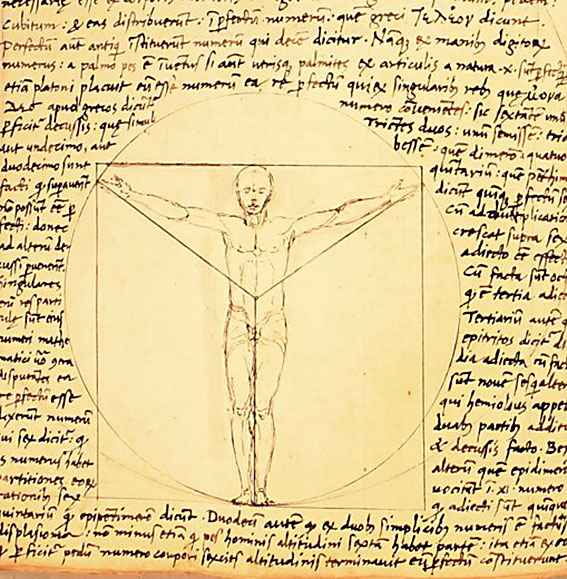

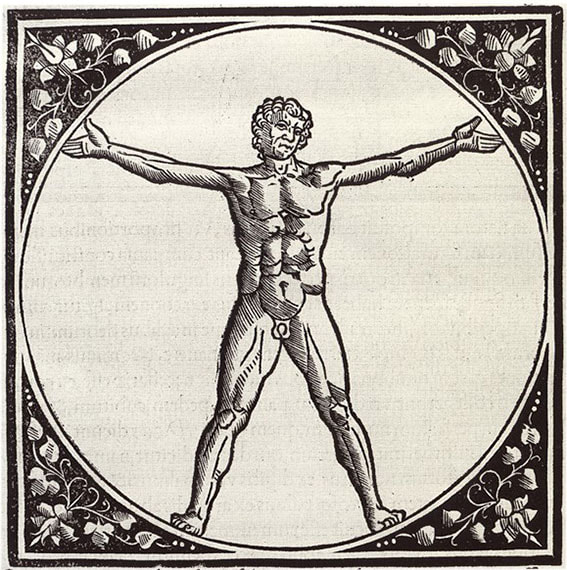

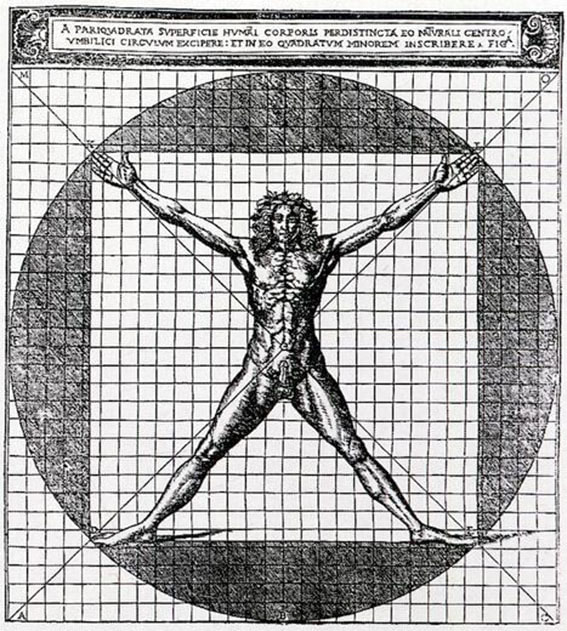

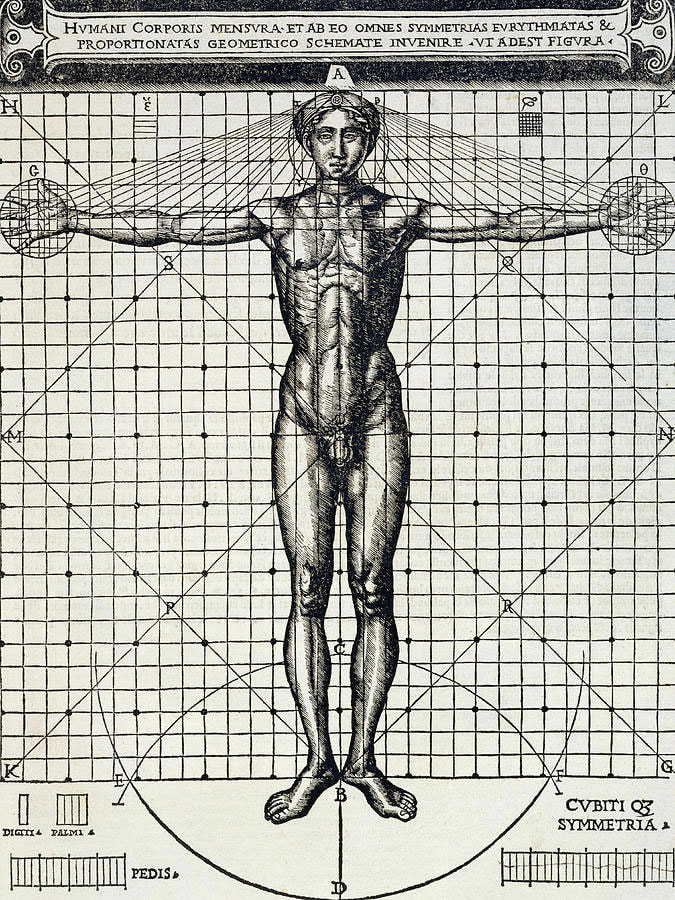

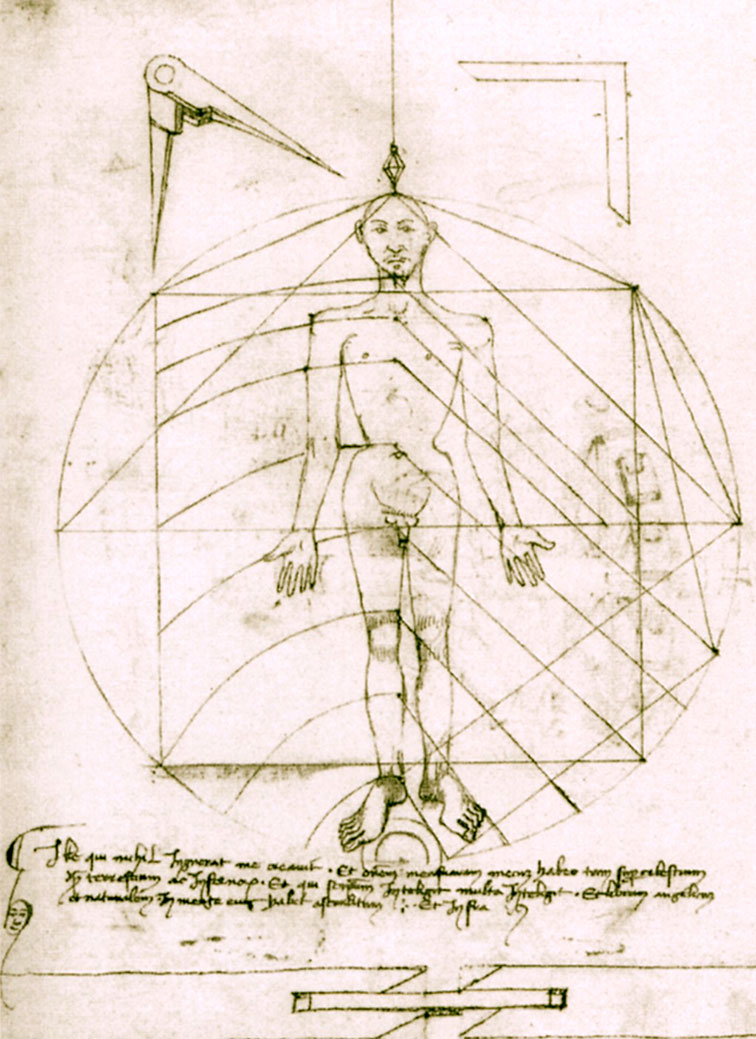

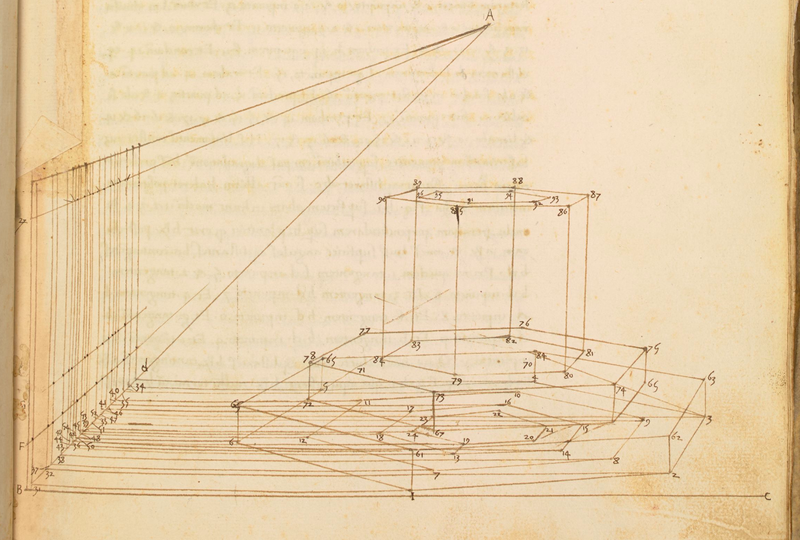

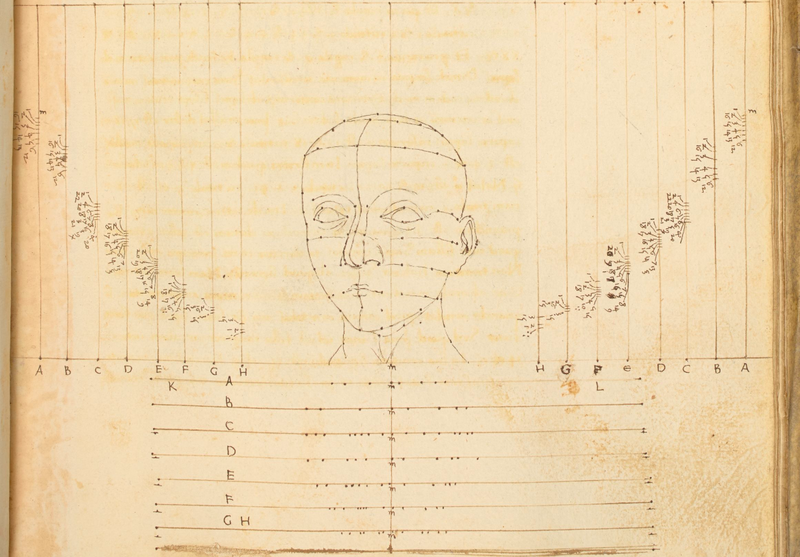

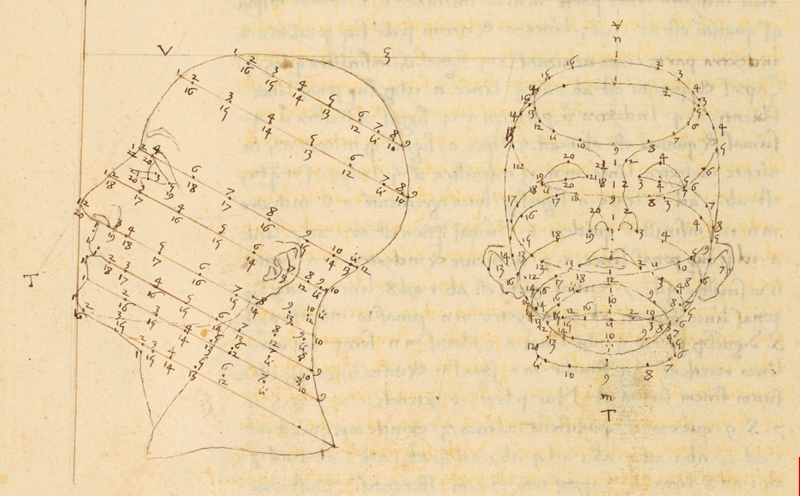

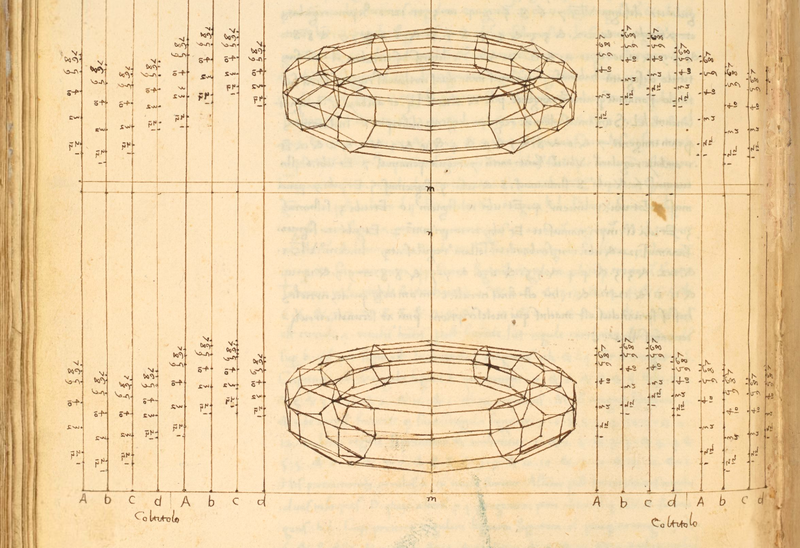

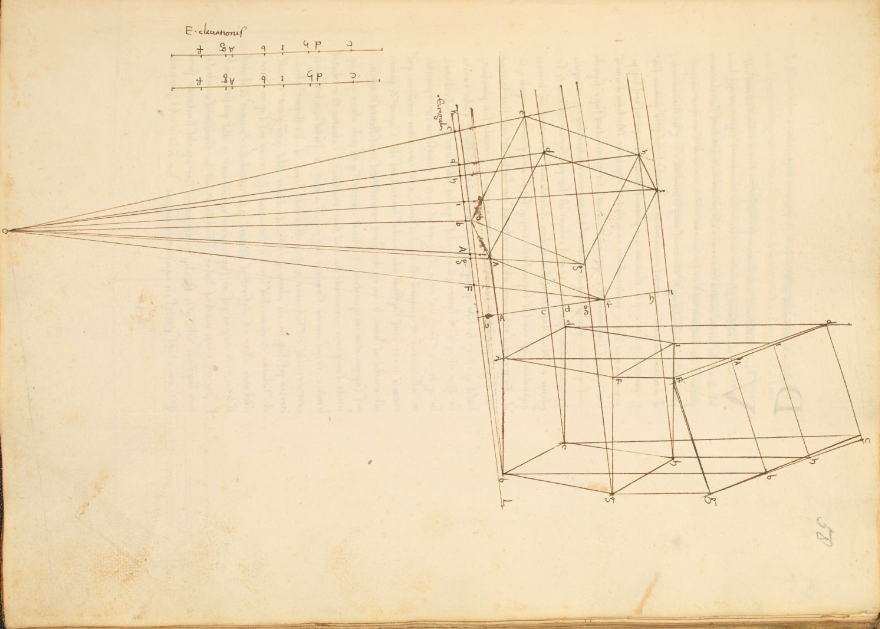

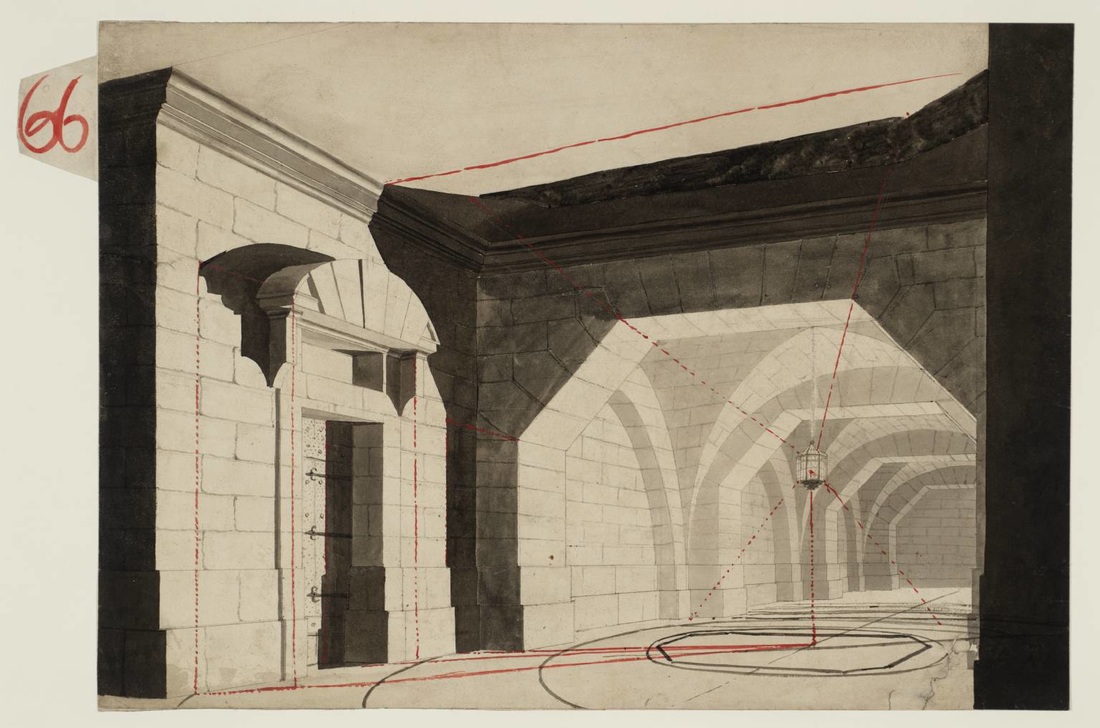

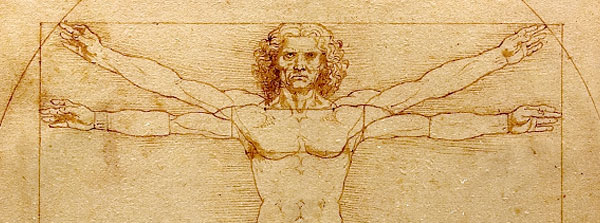

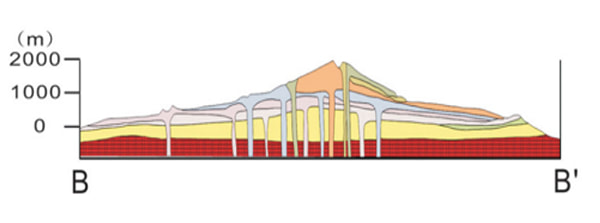

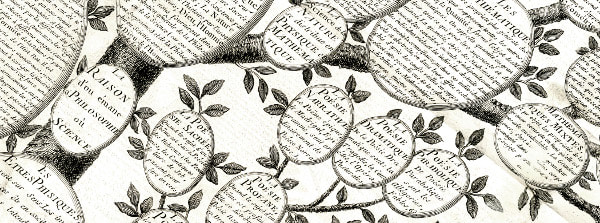

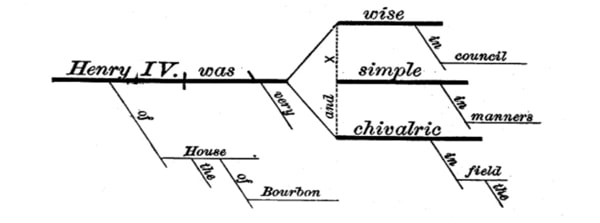

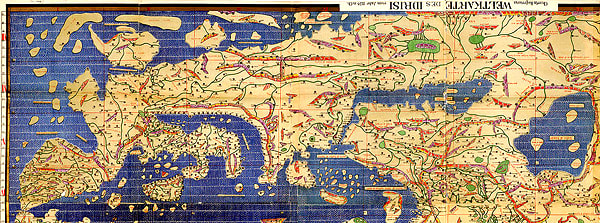

❉ Blog post 20 on diagrams in the arts and sciences delves in to Leonardo Da Vinci's life long obsession with diagram making. From documenting ideas and observations, to elaborate mechanical instructions, blueprints for buildings and sketches for paintings, the diagram was the creative engine that drove his endless pursuit of knowledge and understanding. 1) Glimpse into the left side of a human skull, about 1651 © Royal Collection Trust / Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) The surviving notebooks of early Renaissance artist and polymath Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) reveal a masterful fluency in his use of diagrams. Indeed, during certain periods, his distinctive mirror-written notes and diagrammatic sketches were his medium of choice for observing and analysing the world, rather than drawing and painting. However as we'll see, all of these modes of exploration and expression were intimately connected, especially so in the case of his complex preparatory diagrams that underlie some of his major paintings. Geometry was fundamental to Leonardo’s process of understanding both the visible forms of nature and the hidden mechanisms and forces underlying natural phenomena. His vision of the interplay of these rules of geometry was transformative and dynamic rather than static, as if he observed nature as a process of geometry in action. He was however not merely content to record how something worked, but also strove to find out why it worked the way it did, and it was this insatiable curiosity that transformed a technician into a scientist. (1) In the words of the great da Vinci scholar Martin Kemp, for Leonardo, the "...muscles of the human body worked immaculately according to the laws that governed levers. The flow of the blood in the vessels and of the air in the bronchial tubes in the lungs was governed by the geometrical rules that applied to all branching systems. A flying bird was designed in perfect conformity with the geometry of airflow.” (2) (See figures 2-5) Leonardo studied anatomy and the proportions of the human body throughout his career, and applied this deep understanding in drawings such as The Vitruvian Man (c.1490) (figure 6). This diagrammatic sketch was Leonardo's attempt to answer an ancient puzzle set 1500 before his time by the first century Roman architect and engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (c. 75–25 BCE). In his book De Architectura, Vitruvius founds his theory of architecture on the proportions of the human body, which he considered nature’s greatest work. The challenge was to show how the human figure can be positioned within a circle and a square with the navel at the centre. Ancient thinkers had long invested the circle and the square with symbolic powers, with the circle representing the cosmic and the divine, and the square the earthly and the secular. Leonardo's elegant solution was to position his figure so that the navel aligned with the centre of the circle, but then to position the square off-centre in alignment with the base of the circle. (figure 6) 6) The Vitruvian Man, c. 1490 Pen and ink with wash over metalpoint on paper, 34.6 cm × 25.5 cm Interestingly, a number of other artists from around the same period also attempted solutions to the Vitruvian puzzle, and some comparative examples are included below that highlight the refined technical elegance of Leonardo's draftsmanship and his exceptional knowledge of anatomy. One drawing in particular, made by Leonardo's close friend Giacomo Andrea Da Ferrara, actually predates that of Leonardo's, and its rediscovery in a lost manuscript in Ferrara, Italy in 1986, lead some art historians to question whether or not Leonardo's drawing was actually of copy of his friend's solution. (3) (See figure 9) 7) Perspective study for the adoration of the Magi, c. 1481 Ink on paper, 16.3 x 29 cm, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi Leonardo’s preparatory study for the adoration of the Magi is one of his most remarkable sketches. (figure 7) The immaculately depicted geometry of the tiled floor and the static architecture of the temple interior highlight the turbulent graphic images of the figures and animals depicted within it. British art historian Kenneth Clark described the drawing as "a carefully measured courtyard invaded by a retinue of ghosts". Clark considered it one of Leonardo's most revealing drawings, and the earliest evidence of his scientific attainments in perspective, which to his mind provided "a scaffold for the artist's imagination." (4) Likewise, Martin Kemp considers the sketch an exemplar of the paradoxical combination of contained measure and unconstrained improvisation characteristic of many of Leonardo’s drawings. (5) The reduction of complex natural forms to their underlying geometrical relations was, however, more of an intuitive process for Leonardo than one relying upon the techniques of mathematics. Kemp has suggested that this preference may have been two-fold, both in Leonardo’s own limited abilities at mathematics and algebra but also as an intellectual preference for a more fluid model of a dynamic world based on the beauty of proportions, interrelations and first-hand experience of the world. Leonardo referred to geometry as “the science of continuous quantity’” whereas he referred to numbers and mathematics as dealing with “discontinuous quantities” with little correspondence to the nature of actual physical forms. (6) In his essay for the book accompanying the 2006 exhibition 'Leonardo da Vinci: Experience, Experiment and Design' at the Victoria and Albert museum in London, Kemp discusses Leonardo’s use of disegno as a means to think visually. Disegno was a common term used by Renaissance draughtsmen and is normally translated in English as either drawing (in a fine art context) or design (in the context of applied arts). Leonardo’s use of disegno allowed him to integrate the subjective imaginative faculty or fantasia with the intellect, which in turn achieved expression in the Renaissance concept of science (scientia). Misura was the term used to describe the measuring of proportions, the construction of perspective systems and rules of light and shade, and was regarded by Leonardo as the fundamentally scientific aspect of expression in painting. (7) In works such as the Perspective study for the adoration of the Magi (figure 6), we can see this process at work in the way he combines the fluid, creative, subjective process of disegno with the logic, rigor and measurement of misura. Kemp uses the following quote from Leonardo to support his claim that disegno was considered as the supreme tool that served the eye as a means of investigation and exposition. When Leonardo praises how the eye commands the hand, Kemp suggests that he was essentially making claims about the power of disegno: "Now do you not see that the eye embraces the beauty of the world? The eye is commander of astronomy; it makes cosmography; it guides and rectifies all the human arts; it conducts man to various regions of the world; it is the prince of mathematics; it’s sciences are most certain; it has measured the height and size of the stars; it has disclosed the elements and their distributions; it’s made predictions of future events by means of the course of the stars; it has generated architecture, perspective and divine painting. Oh excellent above all other things created by God… And it triumphs over nature, in that the constituent parts of nature are finite, but the works that the eye commands of the hands are infinite." (8) 8) Codex Arundel, circa 1480 - 1518 (See below for a link to a digitised version) However, it's immediately notable that the systems Leonardo is praising, all relate to the power of diagrams, diagramming, and diagrammatic thought processes, and this becomes even clearer if we consider the examples he refers to: astronomy and celestial charts, the theory and practice of the systems of proportions governing artistic beauty, cosmography (9), cartography and navigation, mathematics including trigonometry and geometry, the analysis of dynamic and static systems in the behavior of earth, water, air and fire, architectural plans, elevations, sections and systems of perspective and the ‘divine’ science of painting with its ‘roots in nature’. Drawing and thinking through diagrams was for da Vinci a natural, almost instinctual means to develop his ideas, communicate them with others and construct a science of painting. However, as with other artists of the Renaissance, Leonardo inherited the tradition for diagramming from Medieval diagrammers before him, as I covered in previously blog posts: Diagrams from the Dark Ages, and Cosmic Diagrams from Alchemical Laboratory. Leonardo's online Codex:Leonardo's Codex Arundel consists of 570 images of dense cryptic notes surrounding technical diagrams. The 283 page manuscript was digitized in 2007 as a joint project between the British Library and Microsoft called “Turning the Pages 2.0,” and can be accessed by clicking here. The Alternative Vitruvian Men: |

||||||||||||

|

"Essentially, perspective is a form of abstraction. It simplifies the relationship between eye, brain and object. It is an ideal view, imagined as being seen by a one-eyed, motionless person who is clearly detached from what he sees. It makes a God of the spectator, who becomes the person on whom the whole world converges, the Unmoved Onlooker."

Robert Hughes (2)

|

RT: I did, but realized early on that I had chosen the wrong subject. I noticed also that

you had studied Biomedicine.

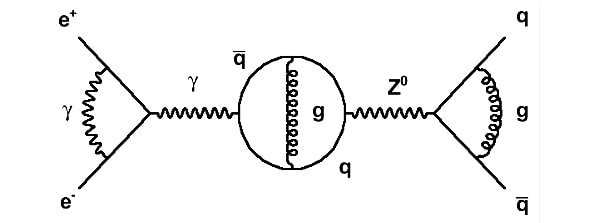

MW: Yes, so I was immersed in diagrams, especially as I specialised in Biochemistry, which as a subject deals with diagrams on many levels.

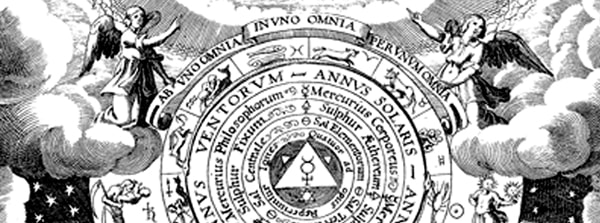

RT: Yes, when I was at school, all the chemistry diagrams and the glassware we used, I still find very exciting, it still gives me a buzz when I look at those diagrams. Also I suppose that Alchemical drawings which are in a sense diagrammatic, but which also refer to broader cultural aspects and spiritual things. But I think it is that combination of diagrammatic mixed with something else where things become very interesting.

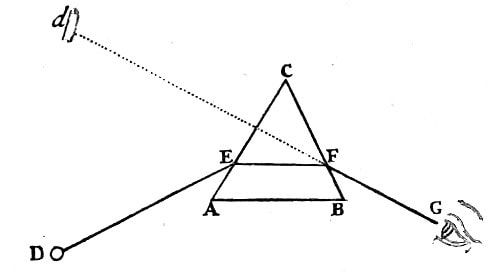

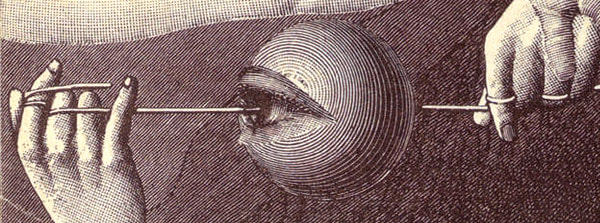

MW: Especially for the initiated few who can decode and read the Alchemical imagery and illustrations such as those in Michael Maier’s books. And you were also interested in optics and optical diagrams ?

Figure 2: Ray diagram from 'OPTICKS:

A treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and Colours of light', Sir Isaac Newton

(forth edition, 1730, Available online here)

MW: That’s something I wanted to ask you about because you had mentioned that you were interested in landscapes, and the idea that maybe the drawings you make are detached, conceptual landscapes. I remember reading 'To the Lighthouse' by Virginia Woolf, and there’s a very short chapter in the middle of the book, which describes time passing in an empty room. But it does so from outside the book, from the detached perspective of an omnipotent narrator, an all seeing eye. I wondered if that was something you were interested in as an artist?

RT: Yes, I think so. I suppose maybe it’s this kind of hyper-consciousness, just this thing, observing, and you just become very aware of time and space, and of yourself as a little entity within this. It’s almost as if time disappears.

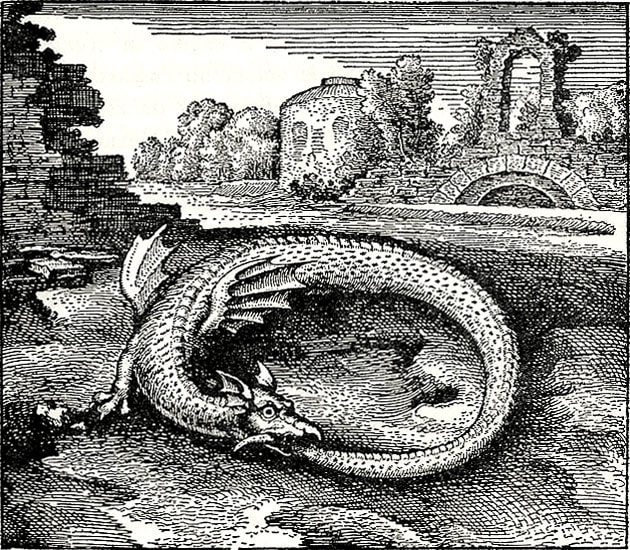

The other thing I remember reading a lot as a student was Nietzsche, and the image of time as a snake eating its tail. He called it ‘eternal recurrence’, where you’re trying to imagine that every moment could be relived exactly the same, so it kind of neutralizes time, because as animals we’re stuck with this as a problem and try to find strategies to overcome that sense of things in the future and things in the past.

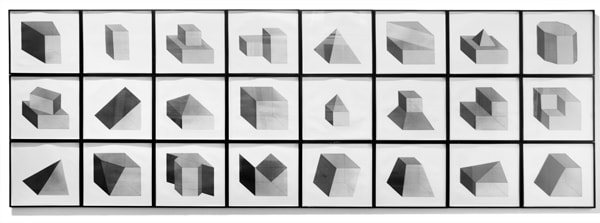

MW: I read that time was something that you would like to take out of your drawings, or perhaps avoid referencing in some way. Also, that you presented the objects in your drawings as Platonic forms, without any signs of wear and tear or reference to scale.

RT: Yes, that’s right, I started off by making objects, but always found it really frustrating in terms of size, or what you make it with. But I suppose that a lot of the twentieth century was about that problem, about objects, and their separateness to us all.

MW: Such as the use of Plinths to present work ?

RT: Yes, for example Plinths.

MW: So did you ever regard your sculptural works as models, as a way to perhaps overcome these issues ?

RT: I suppose I did think of them as 3 dimensional diagrams, but then I suppose that made me unhappy about the materials they were made from. I always imagined whether perhaps it could be made out of perfect marble perhaps.

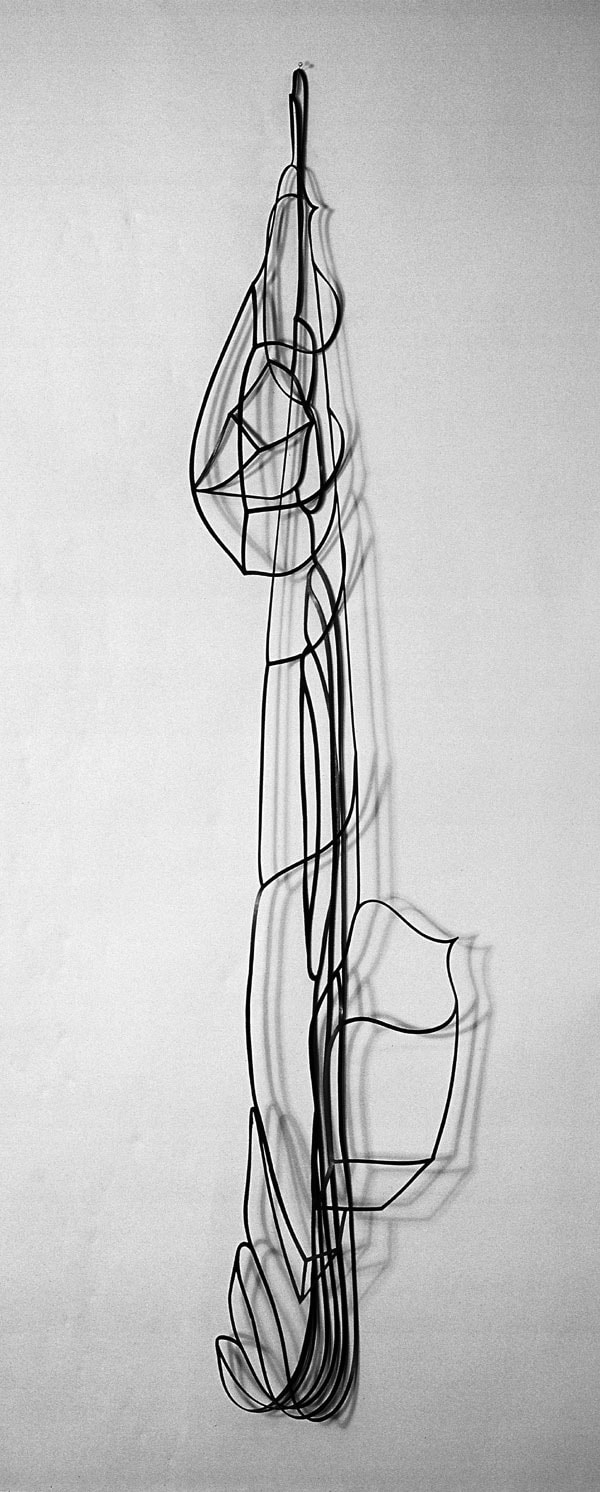

MW: I started to consider making works from elemental materials, such as aluminium or carbon, just to try to deal with the problem of simplifying or neutralizing that issue of materiality. One of the 3 dimensional works that you made called ‘boat’ was made out of rubber wasn’t it ? Hanging as a collapsed frame on the wall, the skeletal form of a boat.

RT: Yes, it’s funny that that particular series of works didn’t end up going anywhere; I’m just trying to remember what the actual sequence was.

I think sometime in the early eighties, I was put forward for a commission; it was one of those completely random invitations to do something. It was for the Savoy Hotel. It was one of those awkward things of, well, do you design sculpture, or do you use something you’ve already got? So I started playing around with drawings and making cutouts from drawings of things. I ended up with some large sheets of rubber and started cutting it out to see whether it was something I could use.

I didn’t intend to end up with something which would hang on the wall, but I did that in the studio by putting it to one side, and it’s quite extraordinary how that works. So it was quite accidental, but was just the recognition of having taken it in to that different area that I didn’t have any control of, so it was quite accidental. It was all cut by hand, so it was a very crisp line cut with a scalpel.

MW: About your working process, you wrote very beautifully about that initial process of orientation, the initial white sheet that you approach, and the infinite possibilities you’re faced with - setting up some kind of initial starting conditions. You used the analogy of the Gothic Cathedral with its ground plans, and then the more organic process of construction that follows that.

There was also another article in the same book (Writing on Drawing: Essays on Drawing Practice and Research) by Terry Rosenberg about ideational drawing, a process of drawing which I though really suited your work very well.

RT: Yes, I mean I must say that I haven’t read fully all of the articles in that book, but have skimmed through them.

MW: There were a couple of essays that really stood out for me personally, yours and Terry Rosenberg’s. I enjoyed the way you talked about your use of perspective, not as a tool to create realistic drawings, but as a tool to allow you to use your intuition.

RT: Well I think that also goes back to that idea of self-consciousness, sort of knowing that you’re this entity that looks at something from the outside.

I used to play around with spatial perspectives, and then I thought that actually one way of neutralizing these issues was just to use it, just to actually use the system. So that to get over that whole issue of viewpoint, for example when you make a piece of sculpture, how do you look at it ? If there’s no best side as it were. So I thought, well if I just take it on full, this issue of perspective, and to absolutely use it as it was set up to use, then it falls by the way side, as an issue.

MW: Turning the problem in to part of the solution?

RT: I think it’s like sometimes in Mathematics, when a problem can’t be solved directly, they will call on a tool from other part of mathematics, and using that tool they can then move from one place to another. But in the end result, that tool disappears, it doesn’t ultimately play a part in the answer, but it has been a useful tool to get you from one place to another.

MW: That reminds me of the role enzymes play in Biochemistry. They’re completely essential to facilitating the process, but don’t take part in a reaction in a way that they are altered themselves in the outcome.

RT: Yes, that’s right, yes. So it is a kind of a vehicle, but then it’s using that perspective that makes me then question how it was originally used in the Renaissance, because when you’re actually working with it on the paper, there are so many interesting things actually going on that art historian looking in from the outside wouldn’t grasp. And it is to do with that idea of play, between the diagrammatic and the spatial element. Perspective isn’t all about creating a space, it is about the surface and how these things operate 2 dimensionally as well.

MW: I was very interested in the way you talked about the depth of space in your drawings, and not using deep space, but keeping things relatively shallow and immediate.

RT: Yes, I think that this also relates to my sense of what these Renaissance artists were doing. The picture that is portrayed of perspective is all about getting everything in terms of the horizon. But I don’t actually think that’s it at all. You are really working in a really shallow space. All those Renaissance paintings are also working in a really shallow space, and I think when you’re actually constructing that on the paper, there’s a real, almost physical connection to the space.

MW: I don’t normally use colour in my work, it’s actually something I avoid, and have for a long time. Then I came across a book by David Batchelor called Chromophobia. He was writing about colour and how it has been perceived as the additional, the exotic, the lipstick. Or at least that’s how it was regarded by artists and writers who saw it as extraneous. And so I’m interested to ask you how you deal with colour in your work.

RT: Well I have to admit as to having always avoided it, as I’ve never understood it. It’s a complete mystery. If I was making a drawing, I can’t see any reason to use colour. But then equally I probably can’t see any reason not to use it. But then I would probably be thinking well, why do I ? But then I know with somebody like Michael Craig Martin, I suppose he’s somebody in the seventies who was producing very austere, paired down work, such as his linear drawings, which were initially all black and white.

But then he probably just stopped worrying and started to use incredibly strong colours in his work. And now the colour is really significant to his work. But its interesting that Michael Craig Martin was taught by Joseph Albers.

MW: That’s interesting, I didn’t know that.

RT: Yes, at Yale. So he would have had a real grounding in colour, and it’s almost as if he, you know – 30 years later or whatever it was – just decided to start using these colours. It is odd how we set rules for ourselves and at the time we kind of need them, but occasionally we just think ‘drop them’, and stop worrying about them.

MW: There were a number of times when looking at your works and reading what you wrote about them that reminded me of mathematics, and the idea of skeletonized forms. The idea of an equation, where the aim is to remove as much information as possible and leave only the knowledge - the process of essentializing something. Also the way that you talk about using intuition, and how intuition can be very immediate, or how it can require you to put the work away for many years. A slow boiler that you come back to much later.

Is mathematics something you’re interested in? Or is it restricted to geometry, or patterns of thought?

RT: Yes, I’m interested, not in the sense of reading books on mathematics, but when I’m near mathematicians and they talk about what they are doing, I do feel an affinity with what they are doing, and I suppose that with my drawings, they become very complex, but I do have that hankering after something really, really simple. I do have this idea that one day I’ll just be able to draw a line, and that that will be the finish! And in a way I suppose you do occasionally see it in some art works – and think that that is just an extraordinary piece of drawing, but then that in a way embodies everything they’ve ever done – 40 years later they’ve managed to make this extraordinary thing !

MW: Richard Dawkins wrote a while ago about the idea of a conceptual space containing all possible genetic variations, a kind of hyper-space of all possible genetic forms, and I was always fascinated by that idea. I think that also Douglas Hofsteader in Goedel Escher Bach, described the idea that Bach, in composing, had the ability to look over all the millions, well almost infinite combinations of musical notes, and was able to see patterns, islands or constellations of musical forms. And I wondered if that idea was perhaps something you were interested in. A vaguely discernible, fuzzy possibility of the form you’re searching for, and how this idea relates to diagrammatic forms.

RT: Yes, I think that is definitely true, and I suppose that one of the things I am aware of is that in some ways, the drawings all start from the same point. That blank paper, that orientation.

MW: The tabula-rasa ?

RT: Absolutely, and you know that it could go in a completely infinite number of directions, and yet there is a sense that there is some solution there - that you setting things up. It becomes very obvious sometimes.

I wouldn’t compare myself to Bach, but I can see that way of thinking - that there is an infinite number of possibilities, but you alight on a particular form that is true for you in one sense or another. It’s hard to really articulate that process.

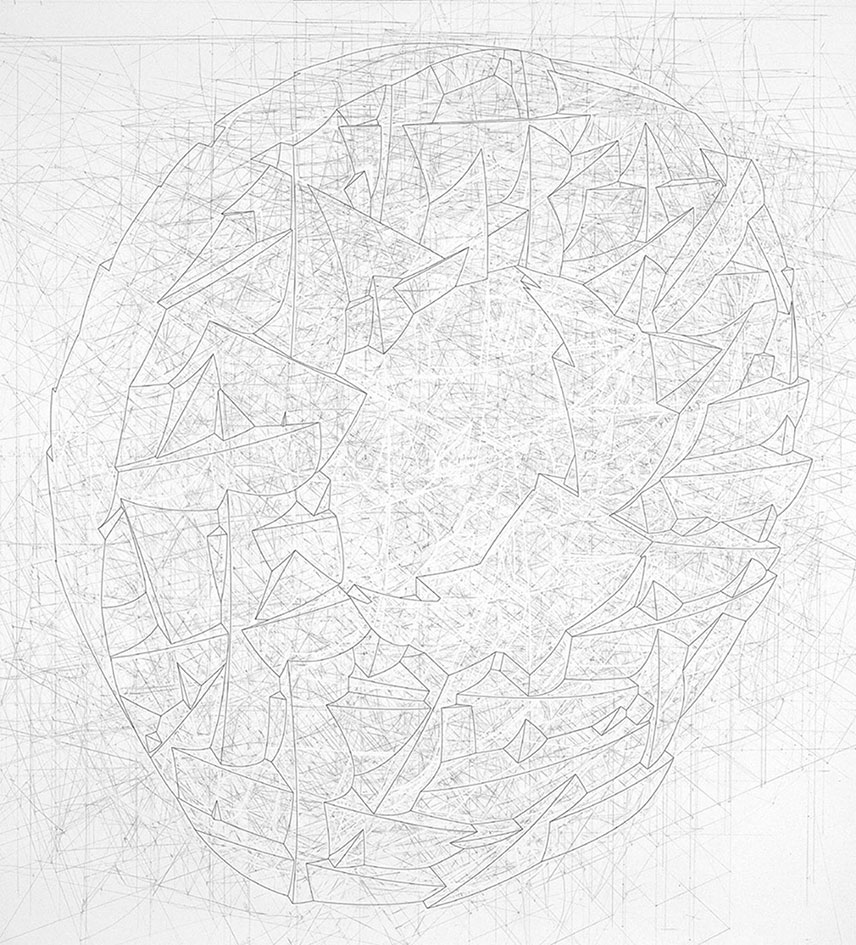

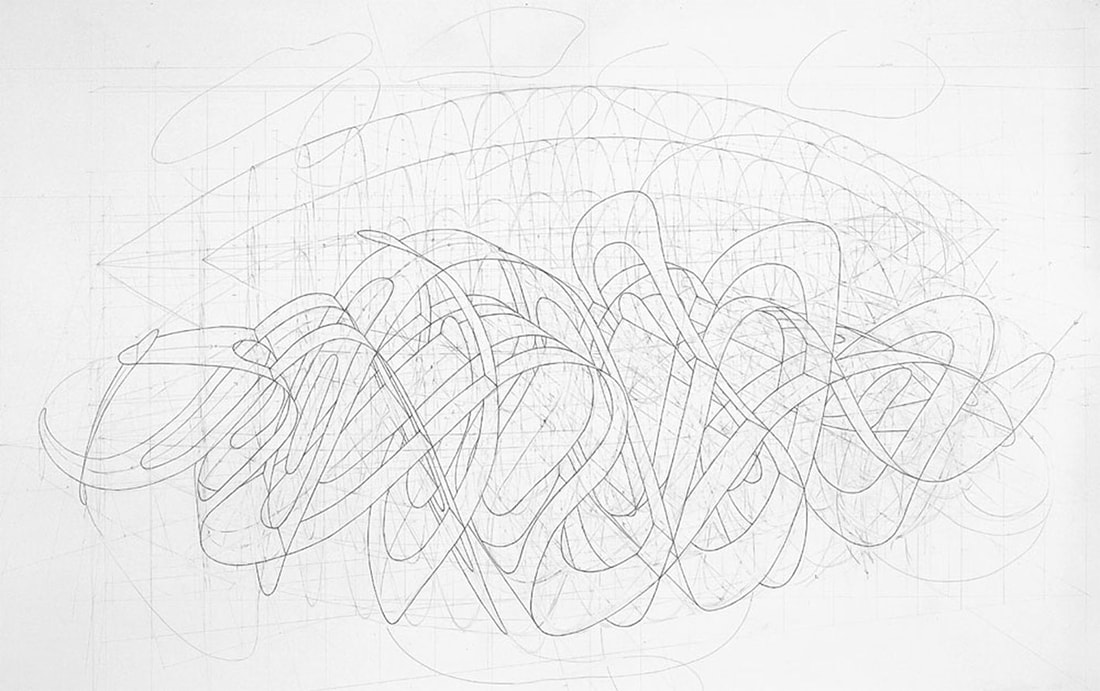

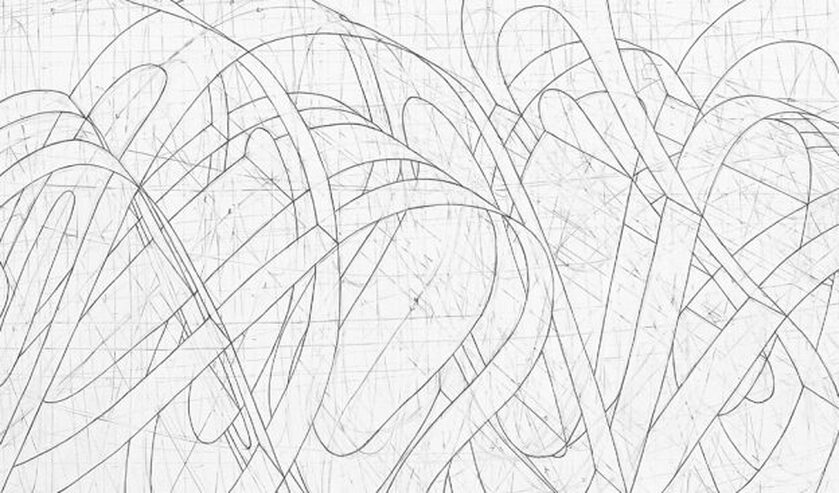

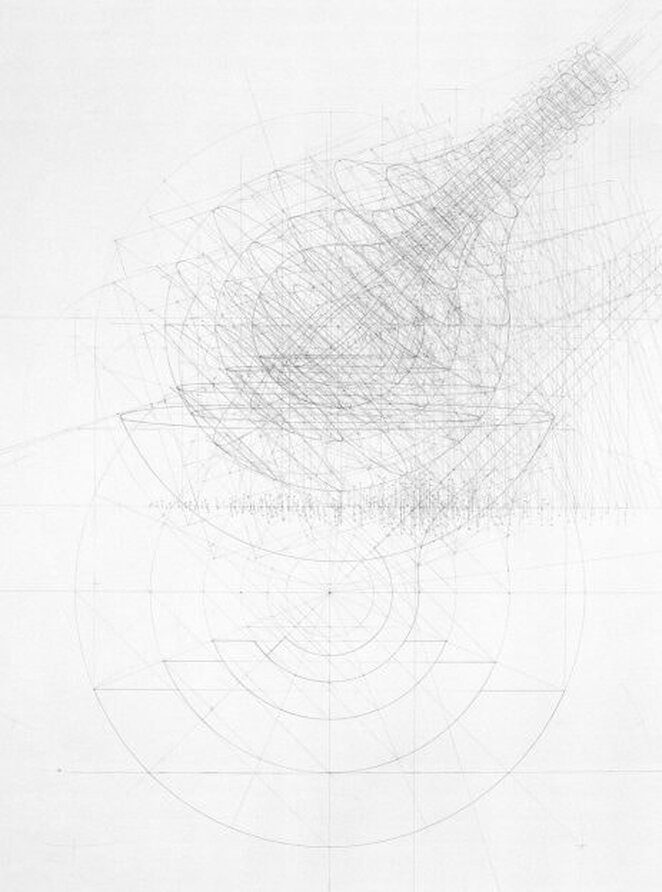

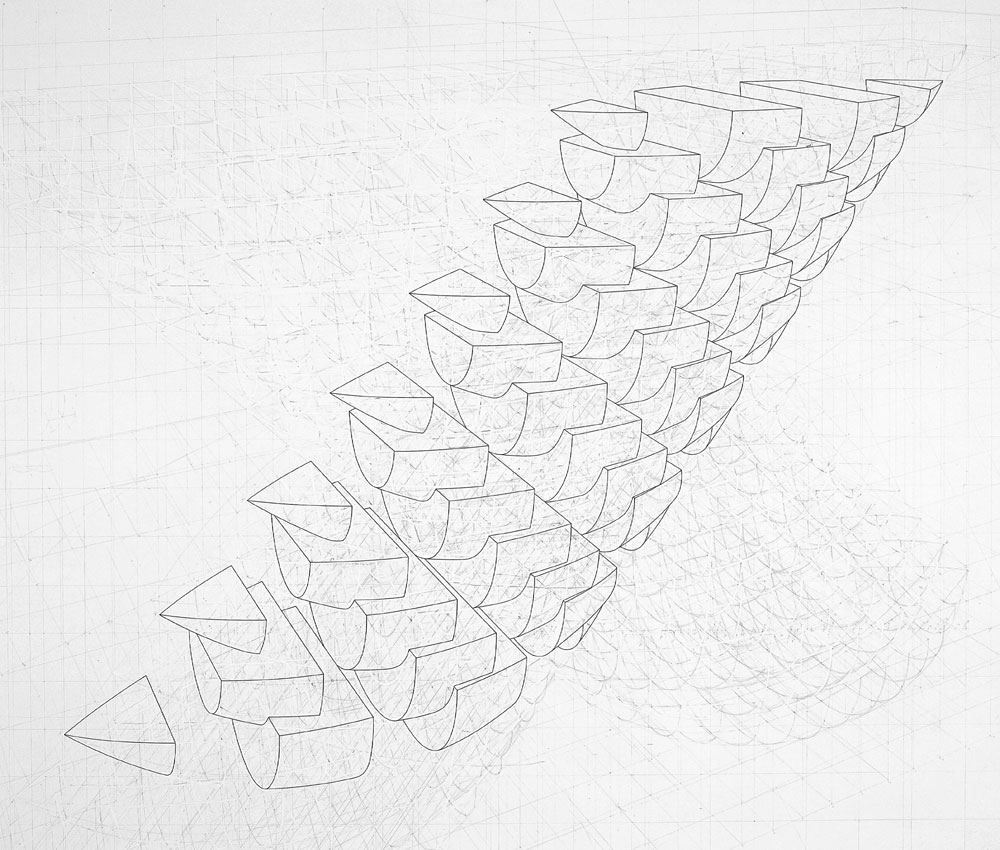

RT: I think when I first started using perspective I was still in that mindset of drawing objects as things in space, but then quite quickly I became aware of how potent the workings-out - you know, the plans, the elevations and so on - how potent they were and how they were working with the kind of forms which were being described. It was also in trying to pin things down, I became aware of the balance between leaving things open ended and tying something down and saying ‘this is that form’. It was that form, but not in such a positive or fixed way.

I stopped using ink on the drawings. I was using ink to go around the forms I was building, but that stopped. And so I started getting a much more subtle interplay between the workings out, and those workings out would be the plans, and elevations, and a myriad of other kind of connections which were being built, a kind of scaffolding.

MW: And you saw inking in as a kind of finishing process ?

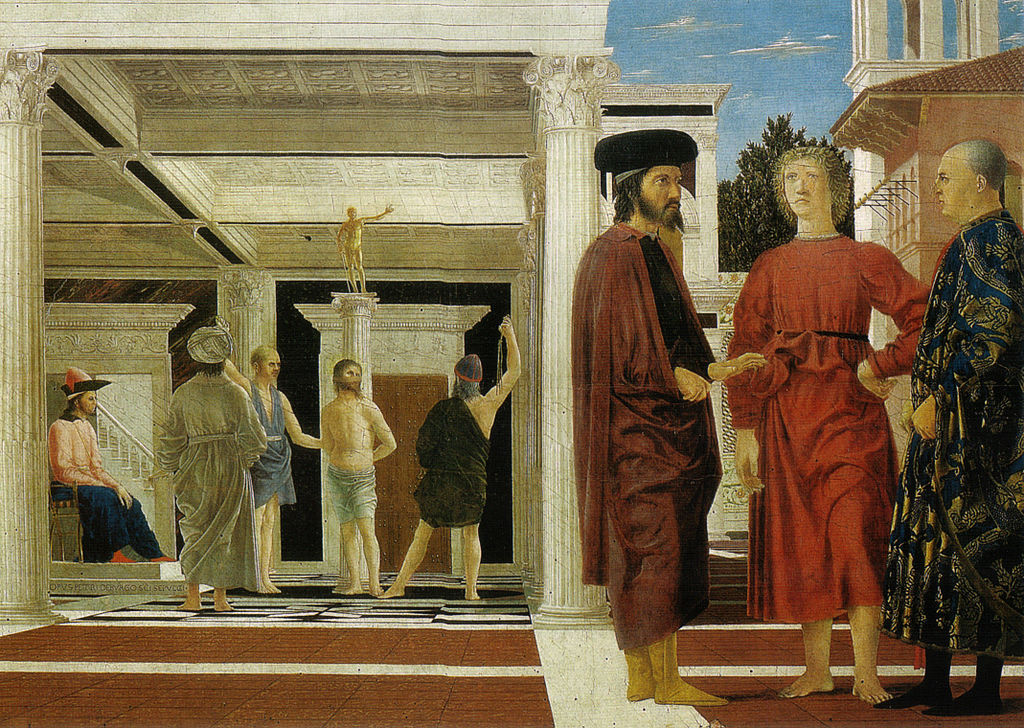

RT: I did. You know you suddenly think that it has in a way killed off the drawings. Not inking became a way to leave the drawing as an open-ended thing. Perhaps when a work is too ‘closed down’ it can end up being very uninteresting. For example Raphael. I’ve never enjoyed looking at Raphael’s paintings because they seem so overly fixed, whereas, Piero de la Francesca’s paintings seem almost as if they are propositions.

Oil and tempera on panel, 58.4 x 81.5 cm

The Flagellation of Christ (outline and outline proportions)

Courtesy of Richard Talbot.

MW: Very early on in coming up with the questions that I wanted to ask in my PhD, I pretty much hit the same problem you did in realizing that I had always studied sculpture, but always made drawings. And I thought of the drawings as sculptural drawings and, luckily for me, my teachers at the time thought the same. So I had to decide whether to investigate the relationship between 2D and 3D diagrams - and thus include sculpture, or the way in which artists use diagrammatic image making to a romantic end, a subjective end; the way in which Marcel Duchamp played subject against object and also struggled with the issues of dimensionality. Where do you stand in terms of subject and object ?

RT: Yes, well I don’t think I would come down either way, because I don’t think that coming down on either side actually gets you anywhere. I suppose that in my student days, this dilemma about the objective and subjective was helped by there being, at Goldsmiths - which was something which was great about Goldsmiths at that time - was that there was a huge range of practice within the staff.

So you did have conversations with people who were systems thinkers, right through to people who were watercolour, or landscape painters. People weren’t trying to ram the stuff down your throat; you were just having these interesting conversations, and then weighing it up about your own situation.

Thinking about what you were doing, what you thought you were trying to do, what you were actually doing ! You know, all those worries you have about, you know, ‘is it art ?’ I found myself really being able to make work when I stopped worrying about what side of the fence I was on, and finding a way of working where I felt as if I wasn’t having to choose one way or the other. But both sides of me could be involved in that hankering after perfection. It’s a case of playing these things off against each other.

I distinctly remember that when I did my MA at Chelsea, the external assessor we had was Paul Neagu, I think he’s dead now, but he was very well known. He was one of the artists who Richard Demarco brought to this country, alongside such artists as Joseph Beuys.

Anyway I remember that the work I’d made at Chelsea had become really quite austere, and extremely minimal, and he said… ‘don’t forget the other side of yourself’, and I realized exactly what it was he meant. That we can easily kind of forget. But then I think that also we need those extremes sometimes, to realize something. We need to go beyond in order to know where the edge was. It’s only when you fall over the edge that your realize there was one !

MW: So there is actually nothing within your body of work that you see as a mathematical proof, some foundation to build upon ?

RT: No, I would certainly never say that there is anything that I’m demonstrating that is mathematical, no. I could say that when I was at Goldsmiths, I was taught by people who were involved in systems, and there were several people I knew, for example Malcolm Hughes working at the Slade, who had students working with experimental systems, building computers to generate paintings and so on; and I always felt that there was a problem in that they knew the kind of thing they were aiming for, and that it just seemed as if, well, you could make that painting without that system.

It was almost as if they were using that system as almost a ‘get out’. The paintings would always end up looking like lots of other abstract constructive paintings that weren’t made with a system, that were just made purely intuitively. And so I have a distrust of the idea of a system, and I think that that system is always, ultimately being driven by you.

MW: What are you working on at the moment ?

RT: Well apart form being heavily tied up in administration, I’ve finished some drawings and I’ve also been playing with film and video, which I can show you if you want.

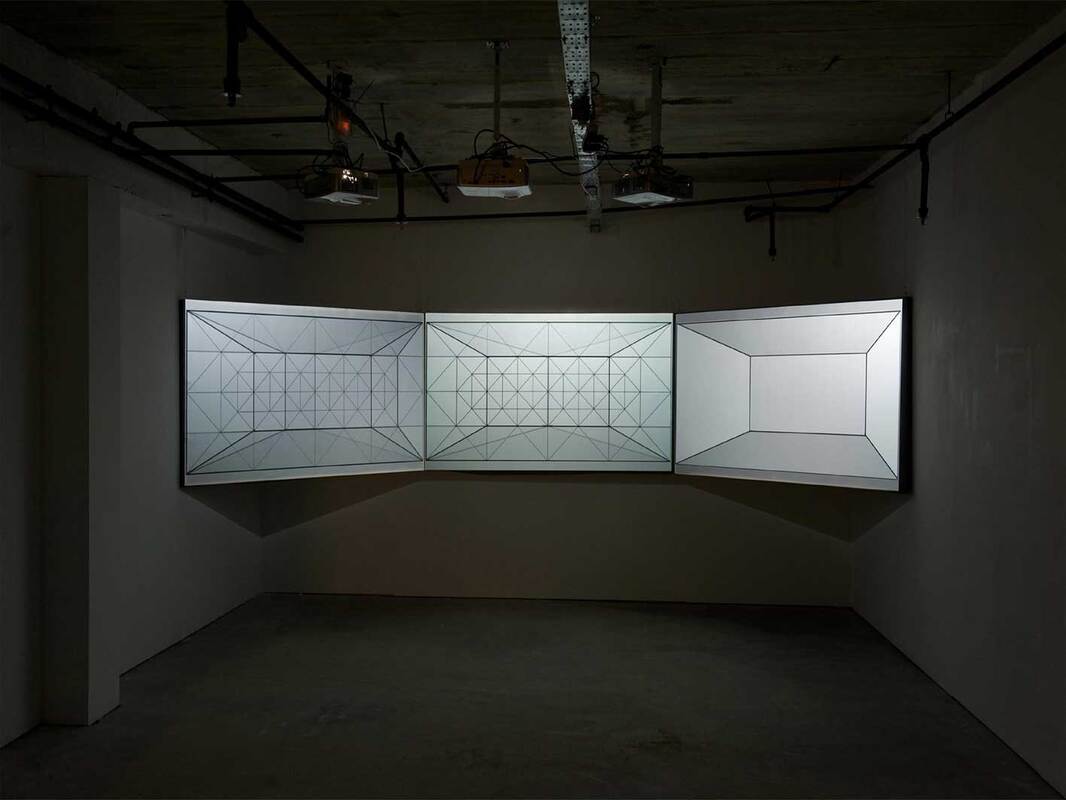

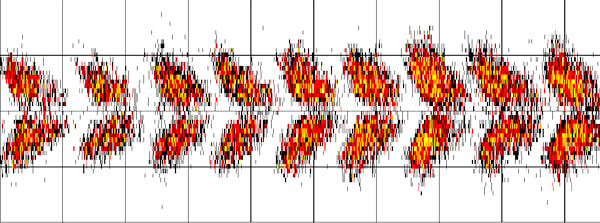

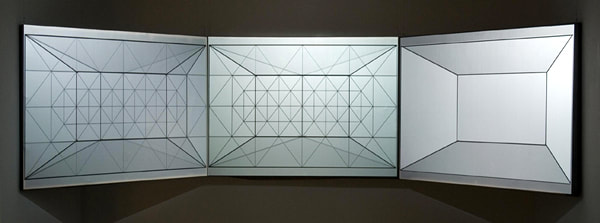

It’s very long drawing, based on a system in a sense, and was a definite play on the standard idea of a single viewer’s perspective. They start with a really basic perspective grid, a ‘unit’, drawn in such a way that I can simply add these units together and extend the space in any direction. Strangely, it adds the possibility of time, in that your eye can travel along the drawing and the space continues always to make sense.

The video is another simple grid that is constantly shifting from the 2 dimensional surface in to the 3 dimensional image. Originally I had intended it to be projected on to a screen, but then I had the chance to project it in one of the large spaces downstairs, and the results were quite extraordinary - because it did actually become part of the space, which wasn’t fully intentional, but those were the results.

The question of the artist’s intention is also an interesting problem I think within the history of perspective; the well-known analyses of key renaissance paintings demonstrate that the spaces in the paintings are sometimes not quite what they seem to be. There is often some uncertainty, yet it is usually thought that perspective is fixed - that it's an unambiguous and rational thing.

MW: Watching the video feels like a trying to solve a puzzle in perspective, there are moments when the lines are like a 2 dimensional pattern of shifting compositions, and then suddenly something in the visual cortex takes over and there’s the impression of instant depth from those very same lines. It reminds me of watching animations of higher dimensional cubes rotating. You think you have understood what is happening and there’s a sudden unexpected shift, you have to grapple with different kinds of depths.

RT: Well - I don’t know - It’s to do with my intention, I’m not settling down to produce something which has a specific result. I know they do result in that, but I’m not setting out to do that.

I am showing this work – I’ve never tried it before. I hope it works… It’s actually going to be projected on to three screens, the same image, butted up against itself, but slightly out of synch. So the whole thing will be ‘shifting’, so that a more complex thing will be going on. I have no idea what it will look like – it might just look awful, but then I’m trying it – for this show.

Grid from Richard Talbot on Vimeo.

Richard's academic studies in to the origins of linear perspective can be downloaded by clicking on the following link:

| speculations_on_the_origins_of_linear_pe.pdf | |

| File Size: | 3315 kb |

| File Type: | |

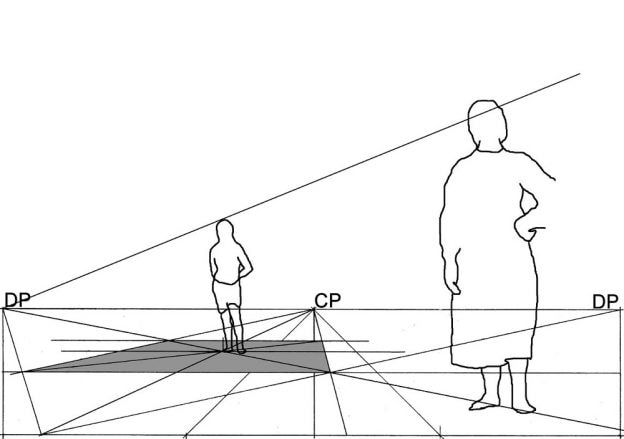

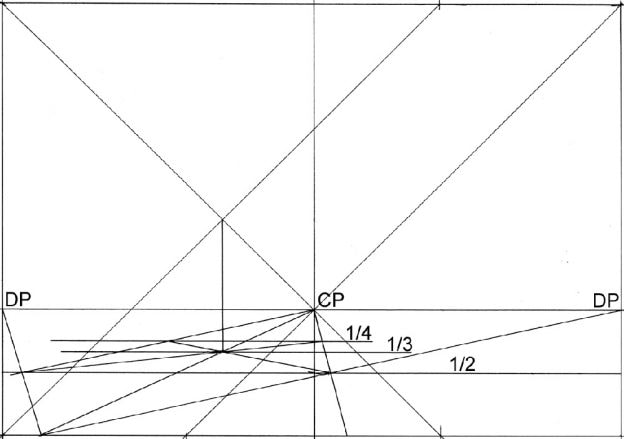

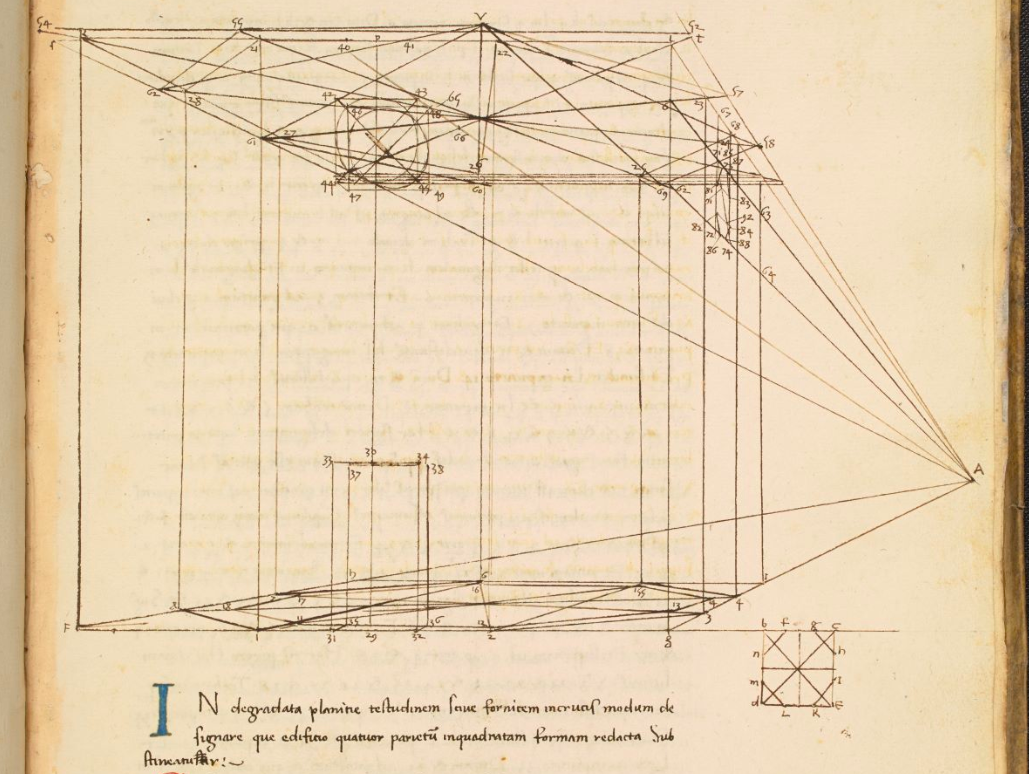

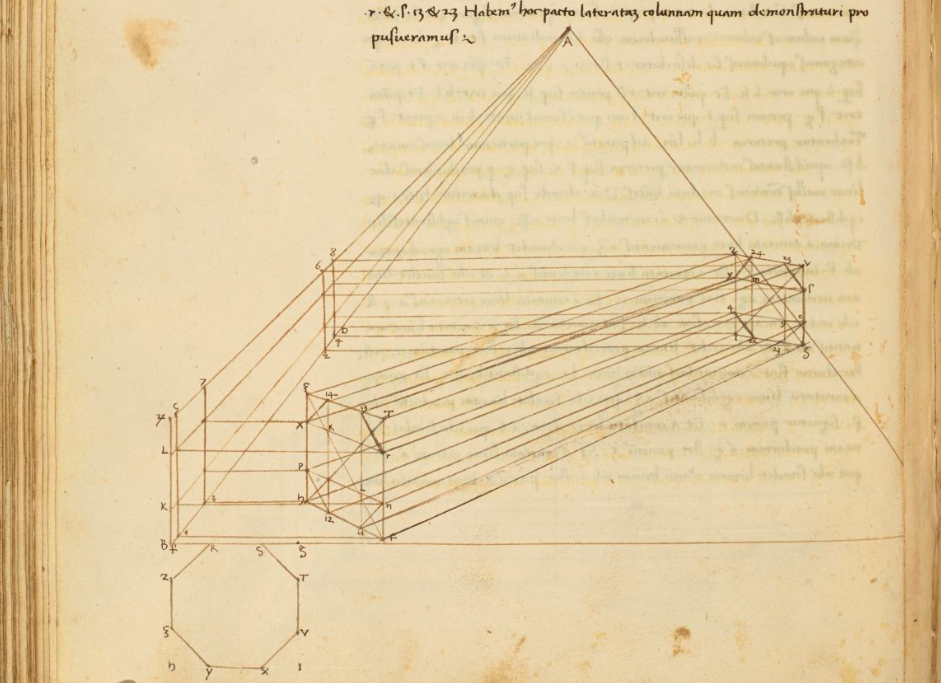

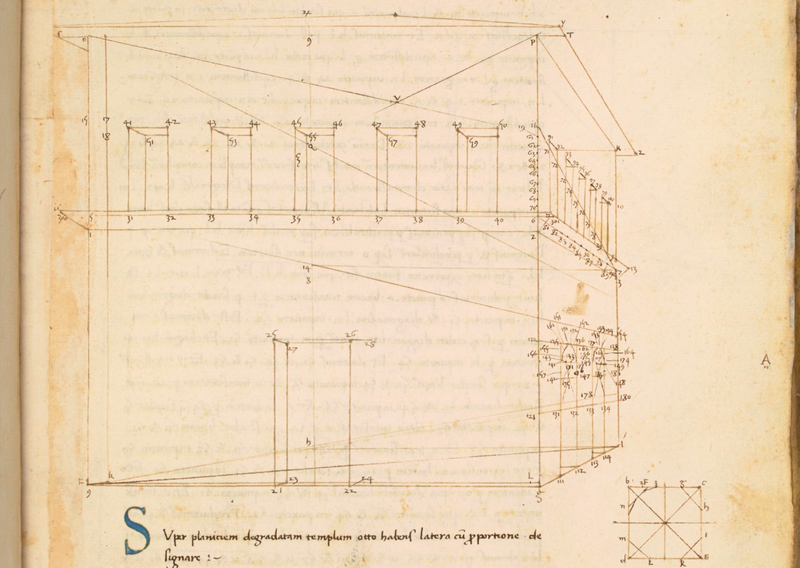

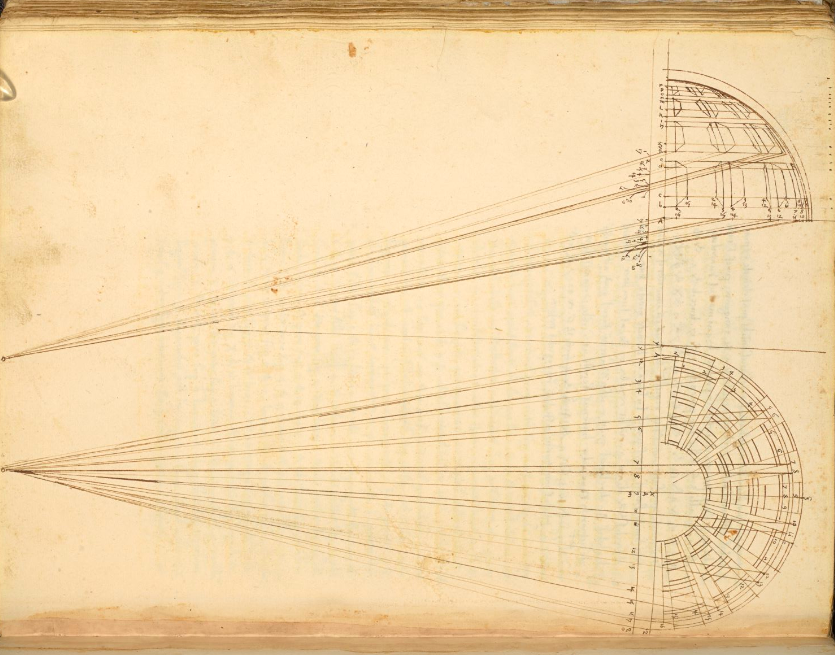

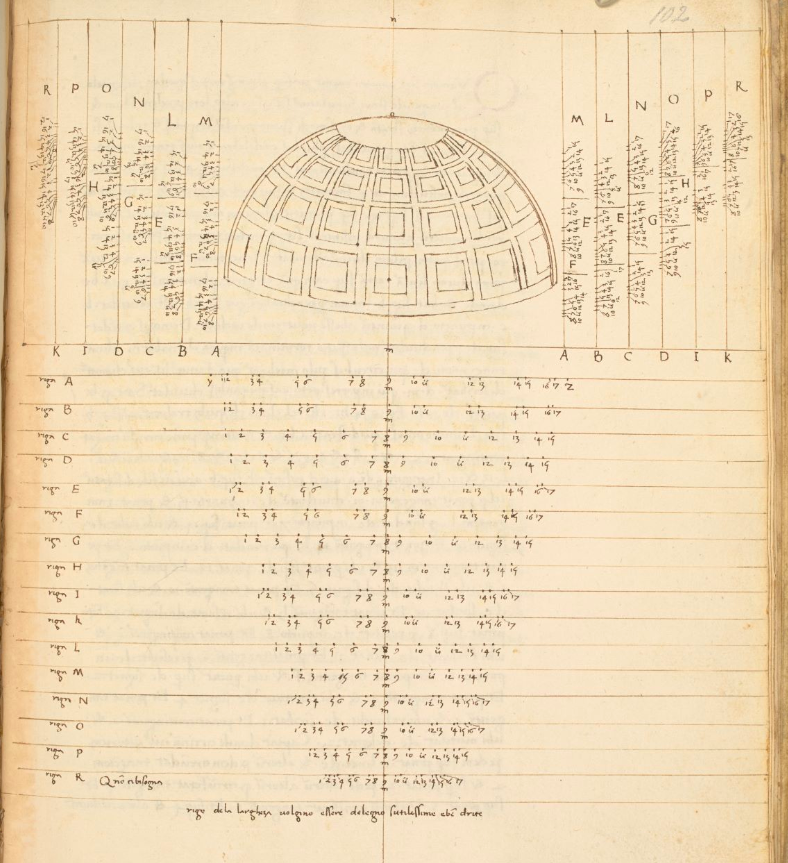

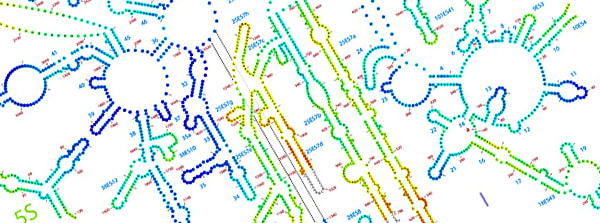

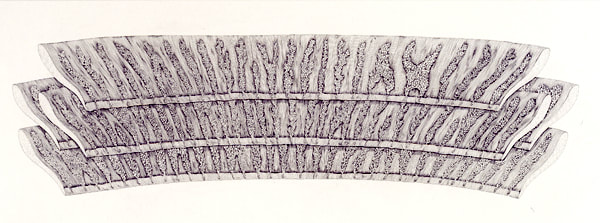

Finally, below are a series of Piero della Francesca's own diagrammatic studies from his book 'De prospectiva pingendi: a treatise on perspective' c 1470 - 1492. The treatise, divided into three books, provides detailed, mathematical instructions, illustrated with numerous diagrams, for creating realistic perspective in illustrations. It was widely known among artists (such as Albrecht Dürer), but also in an academic milieu, where the copies of the Latin translation are thought to have circulated.

The book is available to view online at the British Library here.

1) Talbot,R. (2008) Drawings Connections, In: Writing on Drawing: Essays on drawing practice and research (2008) Intellect Books, UK: Bristol, p.55.

2) Hughes, R. 1980, The Shock of the New, London: Penguin Random House Company, p.17.

Feel free to leave comments or to contact me directly if you'd like any more information on life as an artist in Japan, what a PhD in Fine Art involves, applying for the Japanese Government Monbusho Scholarship program (MEXT), or to talk about diagrams and diagrammatic art in general.

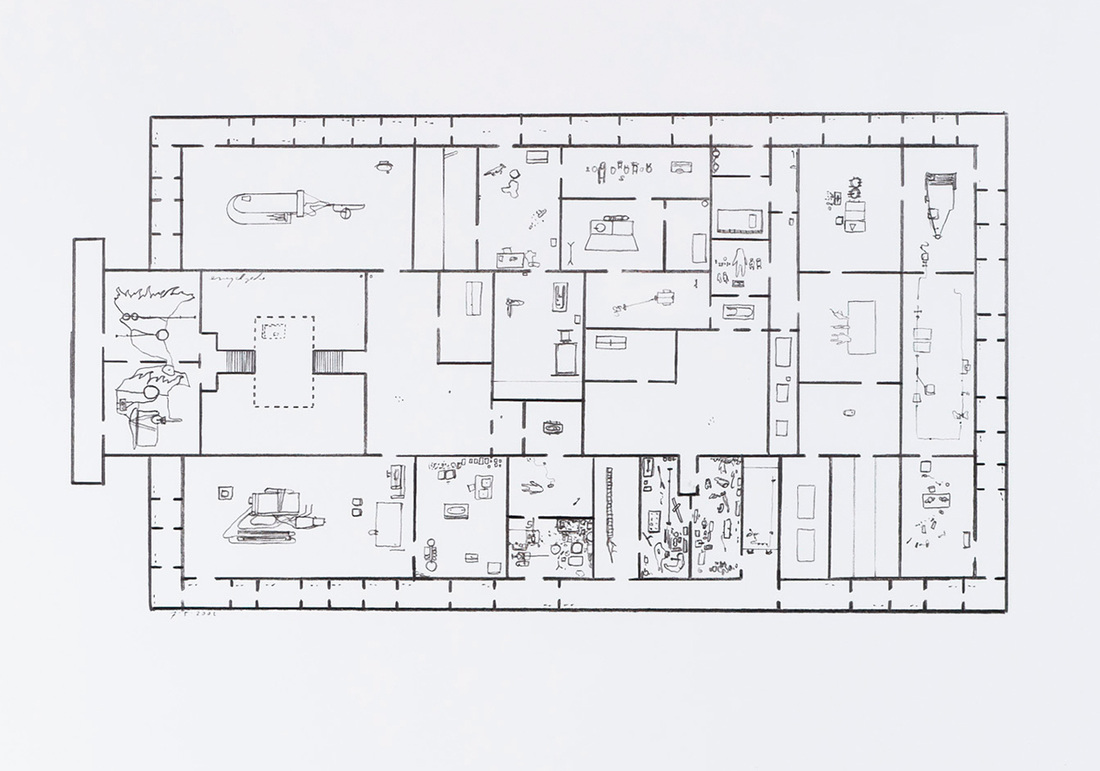

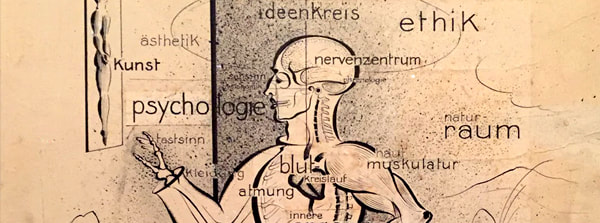

Since 1986, Manders has been constructing what he calls his 'self-portrait as a building', and uses this conceptual framework to represent the fictional artist 'Mark Manders', a distinct alter-ego that he describes as a “neurotic, sensitive individual who can only exist in an artificial world.” (2)

The Diagrammatic format is immediately apparent in Manders' projects as the means by which he marshals the "horrifying amounts of language and materials" that his mind is capable of producing. Diagrams provide method to his madness and imbue his art works with an air of precision, authority and logical rigor, even if we can only guess at their exact function.

iron, ceramic, teabags, offset print on paper, 336 x 185 x 85 cm

Aesthetically, many of the sculptures are formal constructs presented on table tops and in vitrines, resembling scientific models or experiments left unattended. Stephen Berg described these machines and factory-like constructions as “laboratory constellations for uncertainty and unknowable discoveries, production plants for dissident thoughts, transmitters for contacting the fictional.” (3)

The floor plans and delicate pencil drawings show Manders' use of the diagram as a powerful visual and conceptual tool for creation and organisation, whilst the architectural nature of his exhibition installations guide viewers through carefully prearranged objects in a series of constructed environments, which the artist refers to as “memory spaces”. (4)

2002, Pencil on paper

" If you think about the evolution of cups, it’s just a beautiful evolution. The first cups were human hands: folded together, they took the water out of the river. The next cups were made from things like hollowed pieces of wood or folded leaves, and so on. The last beautiful moment in the history of the cup was when it got a handle. After that, nothing really interesting happened with cups, just small variations, mainly ornamental. Many generations worked on it, and now you can say that the cup is finished in terms of evolution.

A few times a day there is a cup very close to my upper leg bone, and I slowly discovered that if you turn an empty cup upside down there is a shadow falling out of the cup, falling upon my leg. I wanted to keep this shadow, have it and own it, so I turned it into an image. " (5)

Mander's heightened awareness of the details of everyday life and the inherent paradox of both their importance and insignificance brings to mind a seemingly timeless quote, often mistakenly attributed to such greats as W.B. Yeats and Bertrand Russell:

" The Universe is full of magic things, patiently waiting for our senses to grow sharper. " (6)

In the case of Romantically Objective Art, that heightened awareness and sharpness of focus is due in a large part to the use of the diagrammatic format, in all its guises.

1) Manders, M. (2010) Parallel Occurrences / Documented Assignments. Aspen Museum of Art, Aspen Art Museum and The Hammer Museum. p.11

2) van Adrichem, J., Bouwhuis J., Dölle M. (2002) Sculpture in Rotterdam, 010 Publishers, p. 60.

3) Berg, S. (2007) Like the night creeping into a shoe. In: In the Absence of Mark Manders. Berg. S. (Ed.) Hatje Cantz. p. 14.

4) Manders, M. (2003) Quoted in: Koplos J. Mark Manders at Greene Naftali - New York, Art in America, April 2003.

5) Manders, M. http://www.markmanders.org/works-a/shadow-study-2/2/

6) Eden Phillpotts, 1991, A shadow Passes. [OXEP] 2004, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [Online], Entry: Eden Phillpotts (1862–1960) by Thomas Moult, rev. James Y. Dayananda, Oxford University Press.

Feel free to leave comments or to contact me directly if you'd like any more information on life as an artist in Japan, what a PhD in Fine Art involves, applying for the Japanese Government Monbusho Scholarship program (MEXT), or to talk about diagrams and diagrammatic art in general.

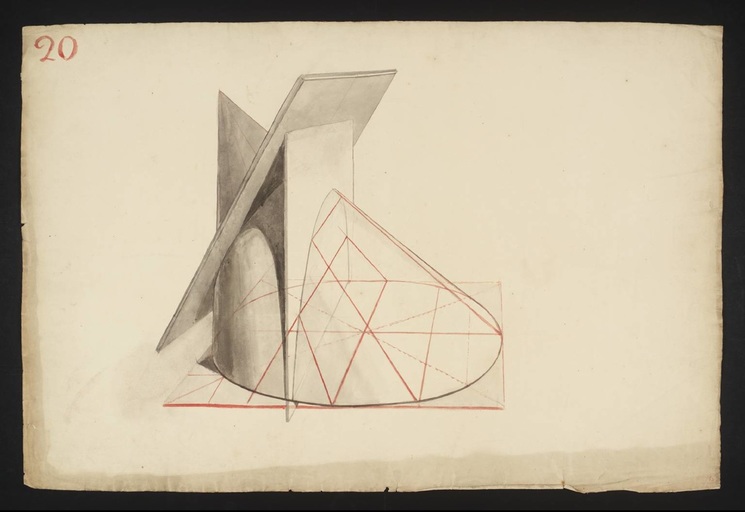

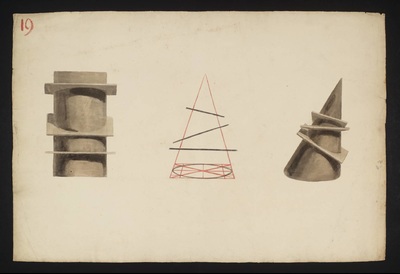

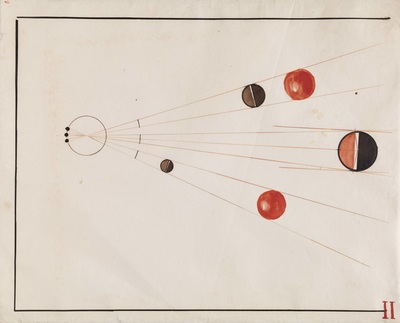

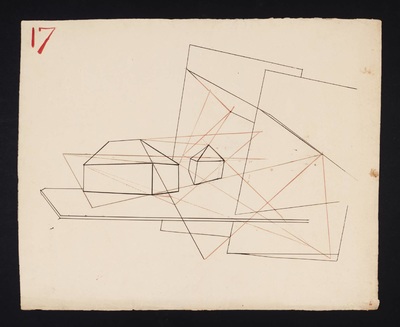

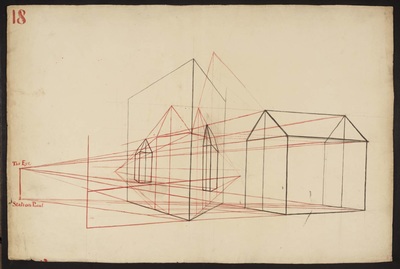

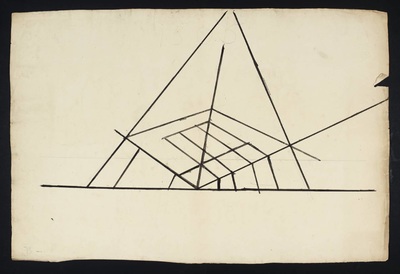

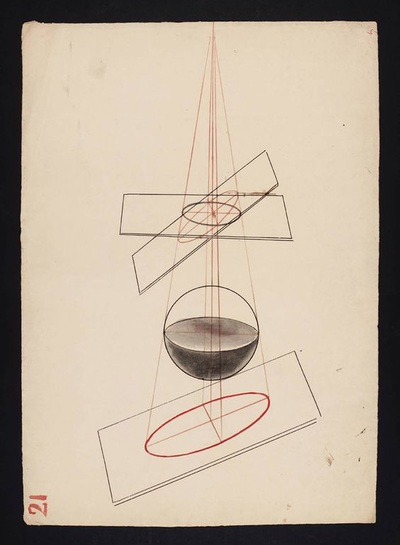

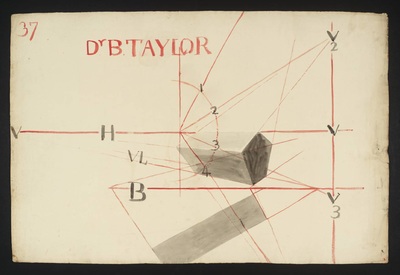

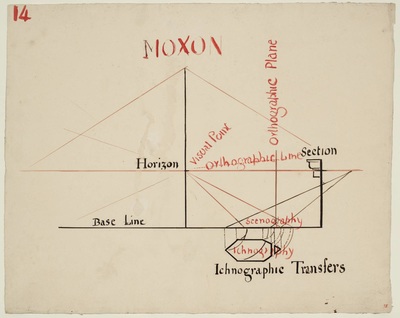

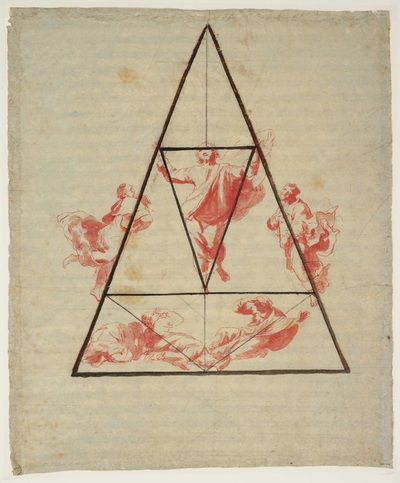

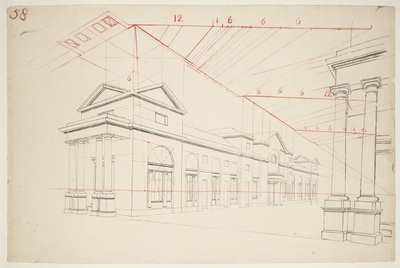

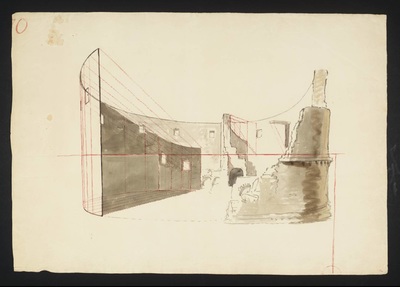

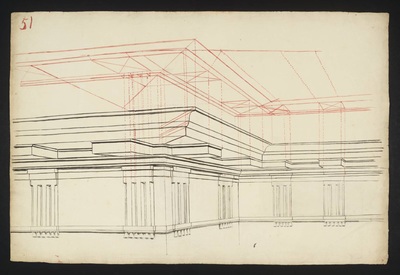

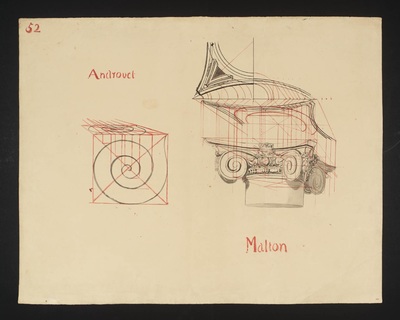

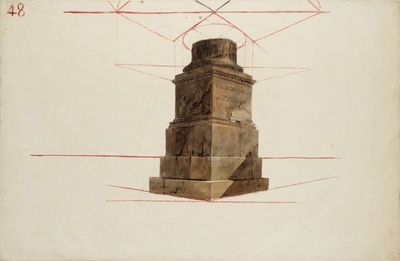

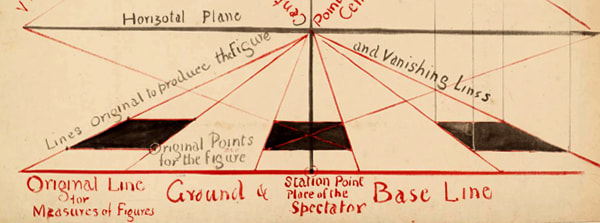

The English Romanticist landscape painter Joseph Mallord William Turner held the position of Professor of Perspective at the Royal Academy for some thirty years, from 1807 - 1837. During this time he managed to deliver only twelve full lecture courses.

Despite being primarily a landscape artist, Turner was in a position to lecture on perspective (principally an architectural specialisation) after having been apprentice to a master of the subject, the younger Thomas Malton, during the 1780s. Turner had also worked as a draughtsman to the architects Thomas Hardwick and James Wyatt, thus giving him a solid grounding in perspective theory and its practical application.

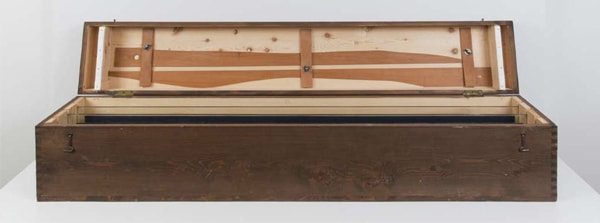

The title of 'Professor of Perspective' was something Turner was particularly proud of, sometimes even adding ‘PP’ when signing works (1). Turner spent over three years preparing his lectures, and during this time created over 170 diagrams to be used as visual aids during his presentations.

These drawings were large in size at approx. 60 x 90 cm (2ft x 3ft), and were positioned by assistants on a stand at his command.

Despite his radical brilliance as an artist, Turner's lectures were far from successful. Audience members complained of his mumbling disorganisation, the rapid rate at which his images were presented, or even of his ambitious attempt to show his complete set of diagrams as a complex diagrammatic backdrop to his lecture.

Fellow Academicians mocked Turner for his 'inane lecturing style', his misuse of technical terms, vulgar pronunciation (he pronounced Mathematics as ‘mithematics’ ), and his liable to stray wildly from the subject he was supposed to be talking about (2,3).

However the diagrams Turner created to elucidate the complexities of perspective that he struggled to explain verbally, remain even today refined, lucid and strikingly contemporary in appearance.

They provide excellent examples of what the American Philosopher-Scientist Charles Sanders Peirce described as 'Moving Pictures of thought', in that one can literally see a given argument and experiment, model and confirm the ideas within ones own mind (4).

As one of the students in attendance at his lecture later reported, Turner's diagrams ‘were truly beautiful, speaking intelligibly to the eye if his language did not to the ear’. (5)

This Series of Diagrammatic drawings holds a fascinating position in art history, in that they were made by one of the preeminent Romantic Landscape painters of the period, and yet reveal a mastery of the objective and technical rules of optics and perspective.

Turner, however, was an artist of his time, and in the words of Brian Lukacher, the ‘mathematical rules of perspective, he believed, crumble before the higher metaphysics of the artistic mind fixed on the immeasurable’.

The 'Romantic / Objective' nature of such diagrammatic images was the subject of my PhD thesis, chapters of which are available for download from the research page of this website.

1) Judy Egerton [and Clifford Ellis], ‘JMWT PP’: A Selection of Drawings Made by Turner to Illustrate his Royal Academy Lectures as Professor of Perspective, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1980, p.1.

2) Mr Turner's lectures at the Royal Academy, The New Monthly Magazine, 1 February 1816, p.60.

3) Annals of the Fine Arts, vol.4, London 1820, p.98.

4) CP 4.8-11

5) Richard Redgrave, A Century of British Painters, 1866, p.95.

For more information See:

Andrea Fredericksen, ‘Royal Academy Perspective Lectures: Sketchbook, Diagrams and Related Material c.1809–28’, June 2004, revised by David Blayney Brown, January 2012, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/jmw-turner/royal-academy-perspective-lectures-sketchbook-diagrams-and-related-material-r1131857, accessed 18 March 2016.

Dr. Michael Whittle

British artist and

researcher based

in Macau

Categories

All

Alchemical Art

Anatomy

Arakawa And Gins

Architecture

Bauhaus

Contemporary-art

Contemporary-art

Duchamp

Genetics

Geology

Geometry

JMW Turner

Leonardo Da Vinci

Literature

Mathematics

Medieval Art

Musicology

Oskar Schlemmer

Perspective

Physics

Romanticism

Sol LeWitt

Surrealism

Theatre

Archives

April 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

June 2022

June 2021

August 2020

October 2019

August 2018

January 2018

November 2017

October 2017

April 2017

November 2016

October 2016

September 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016