|

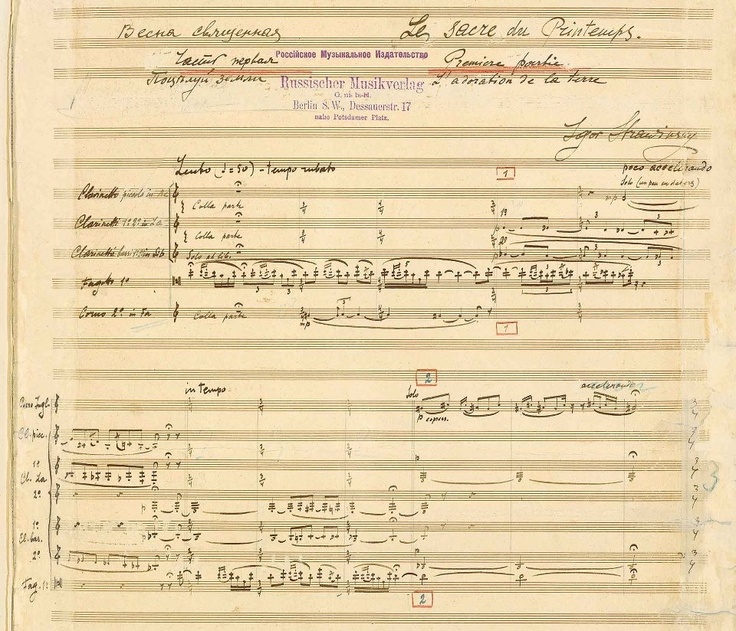

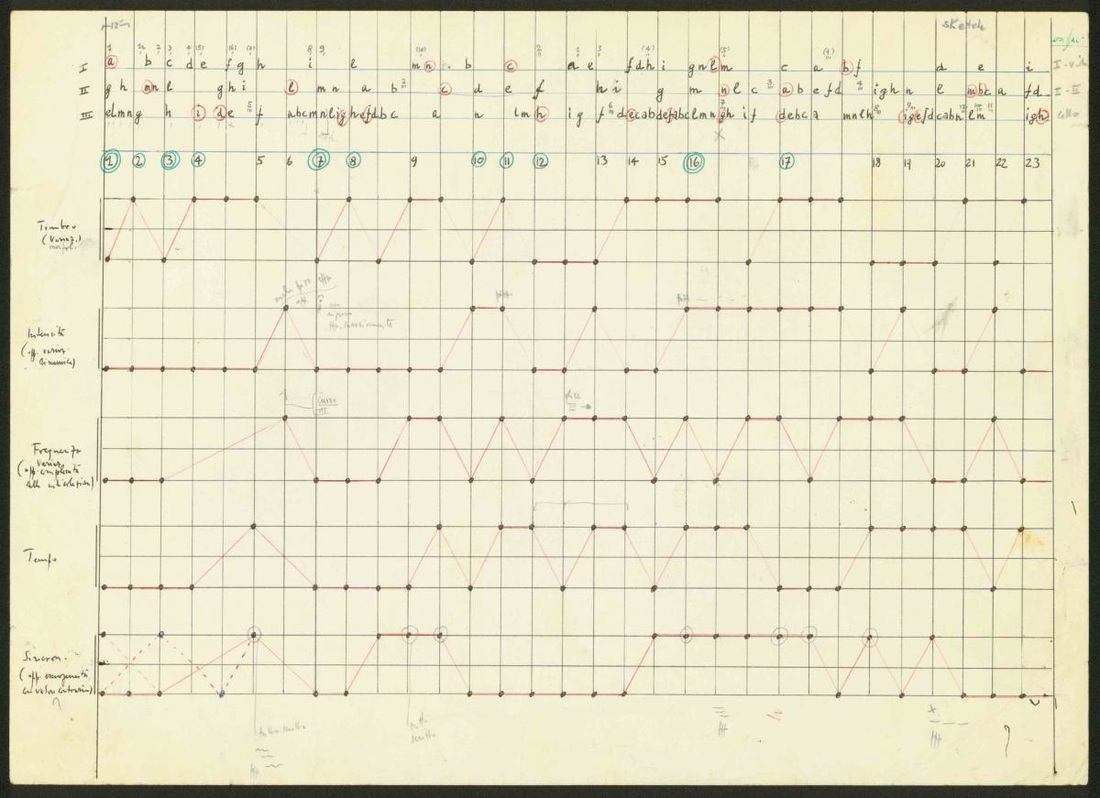

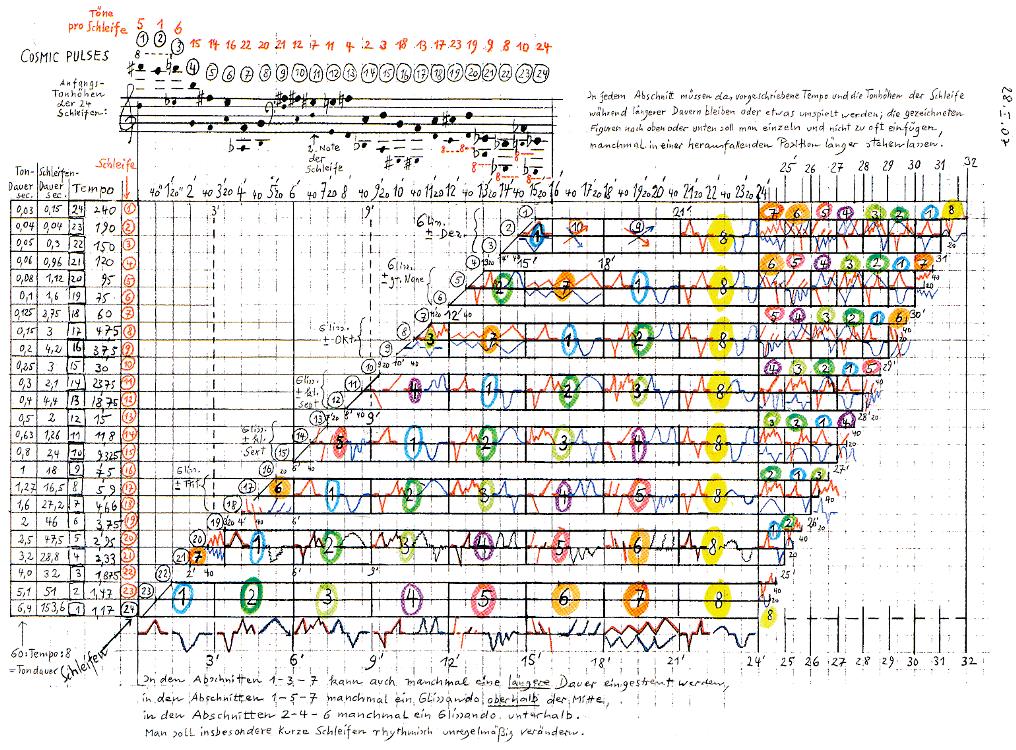

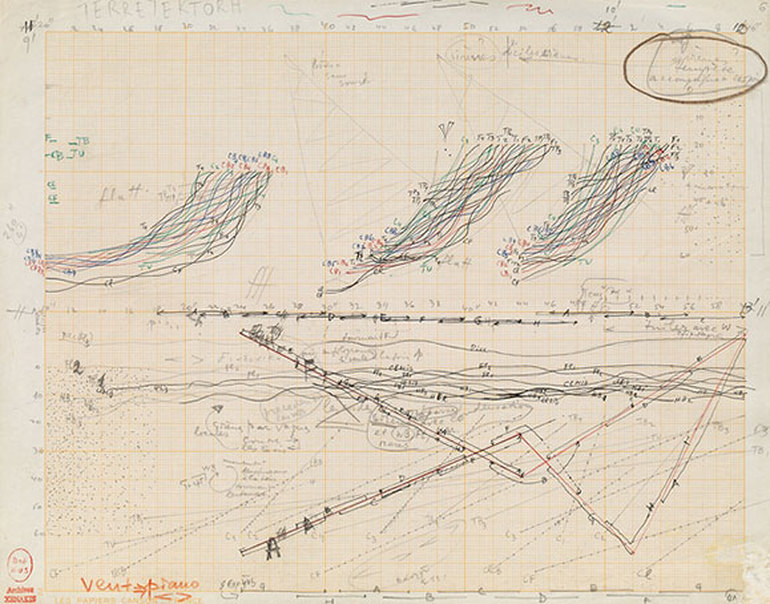

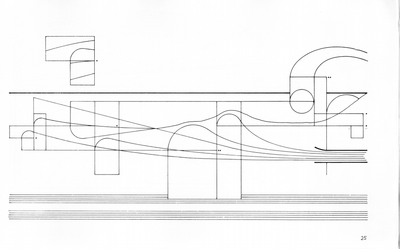

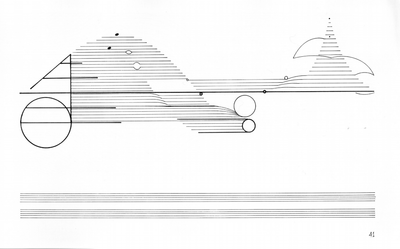

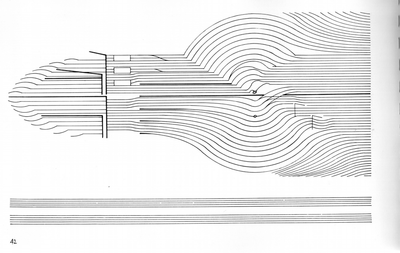

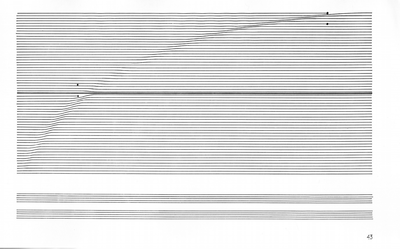

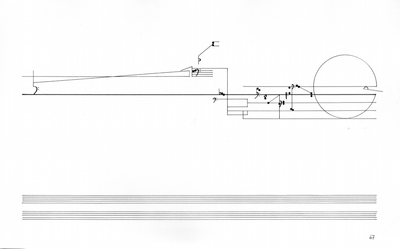

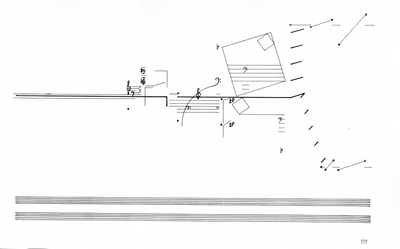

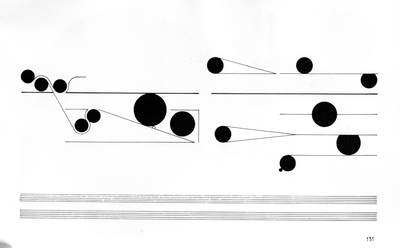

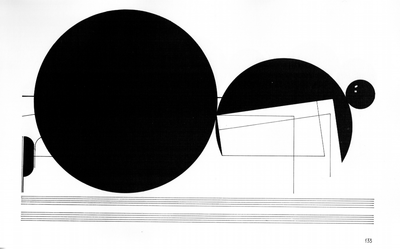

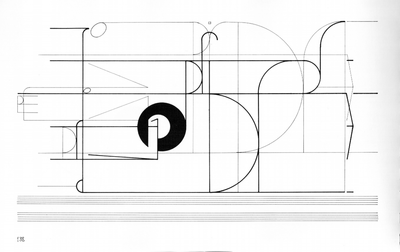

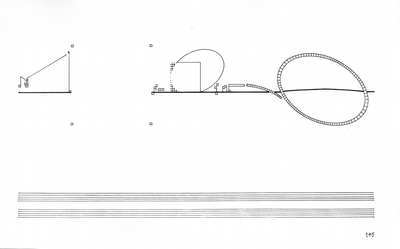

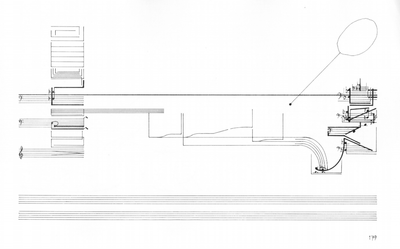

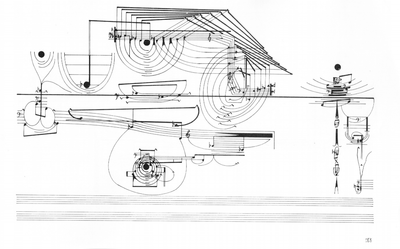

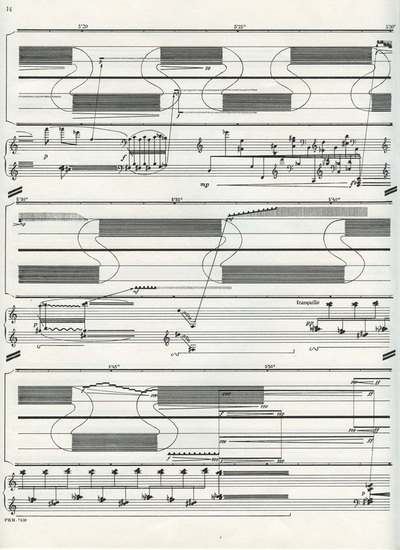

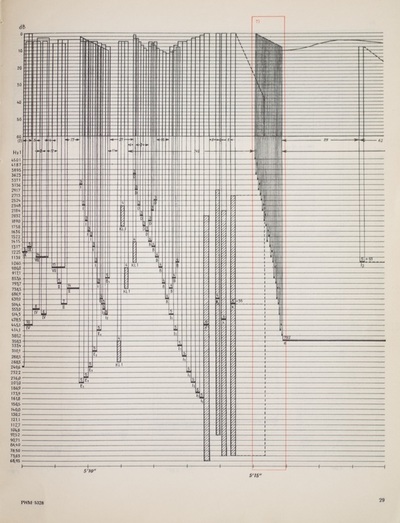

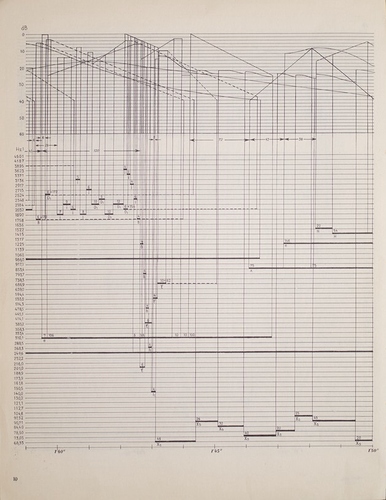

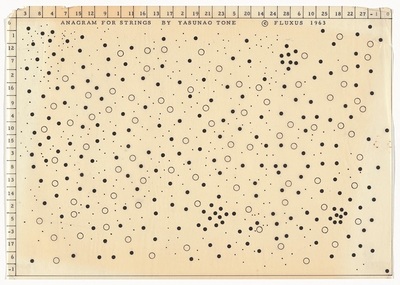

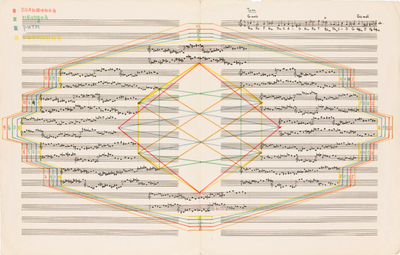

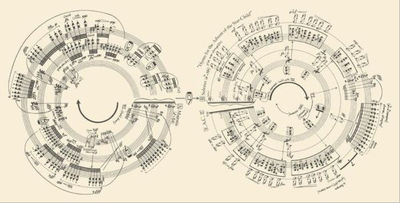

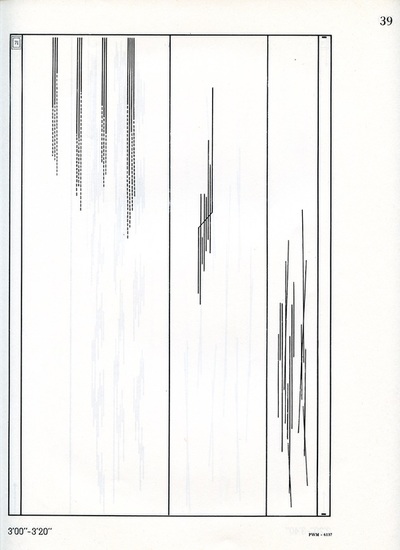

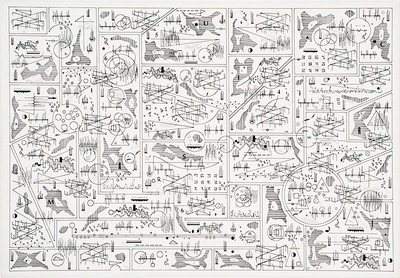

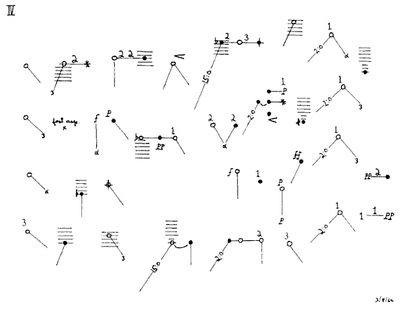

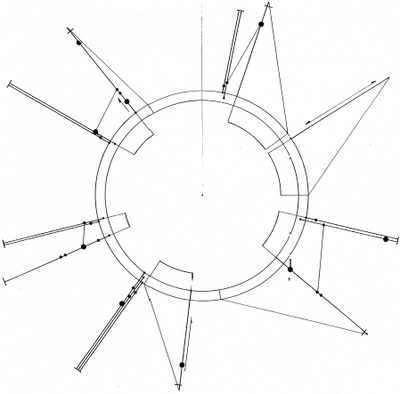

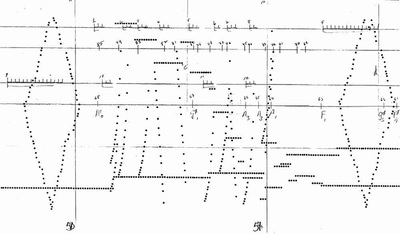

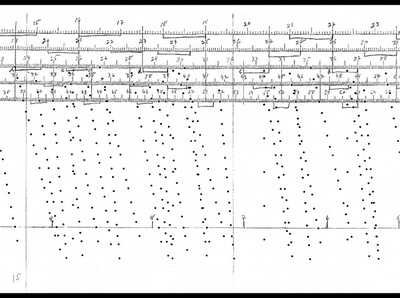

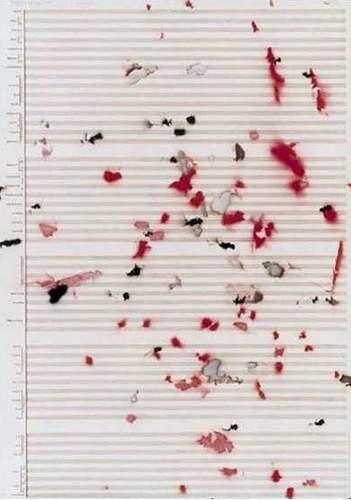

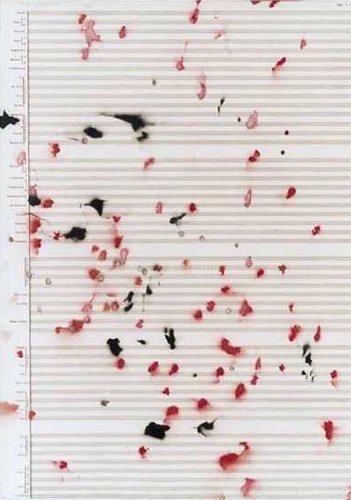

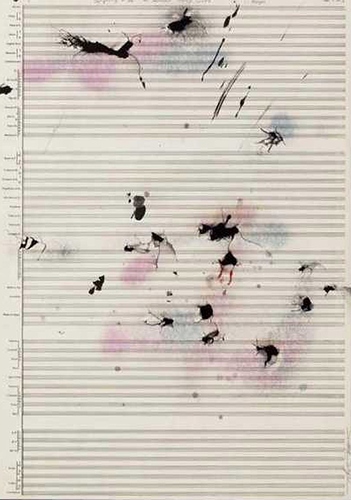

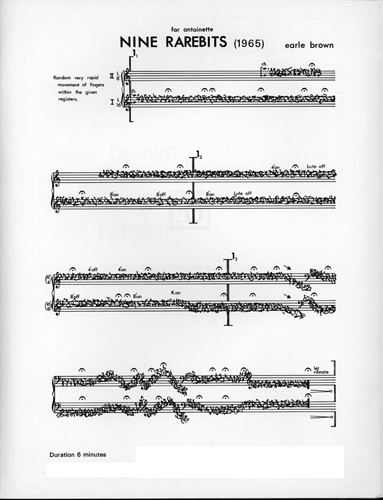

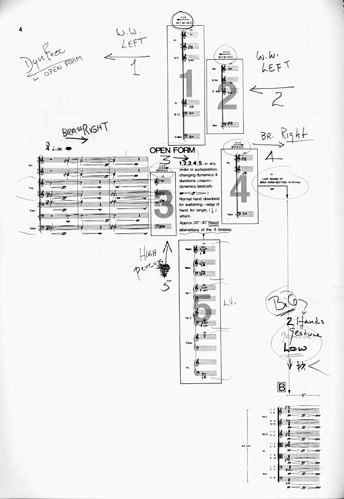

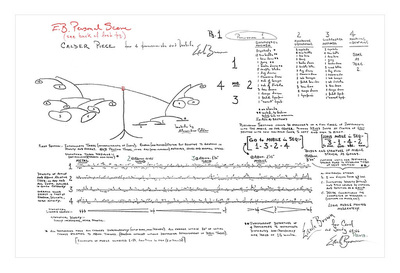

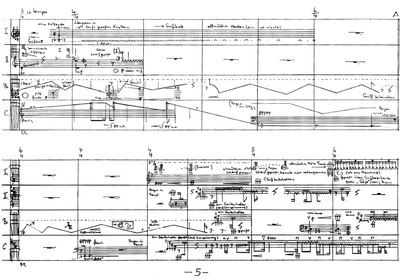

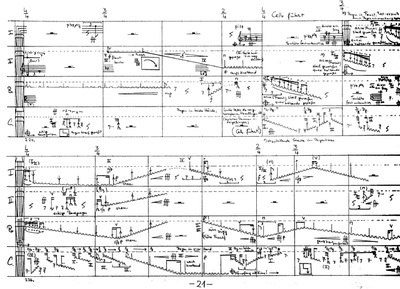

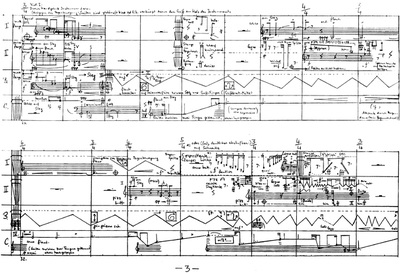

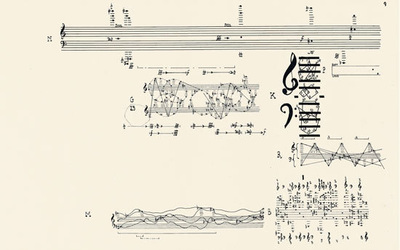

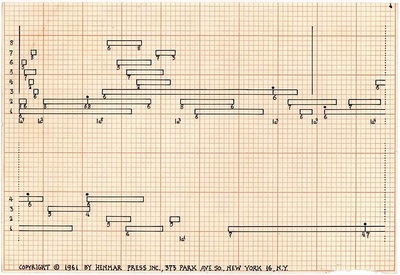

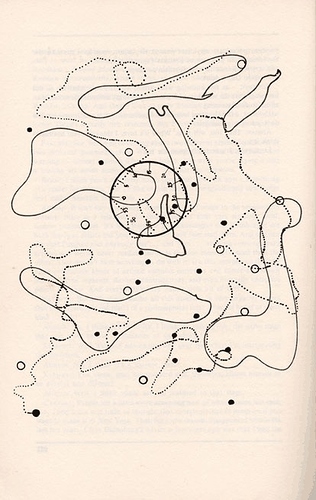

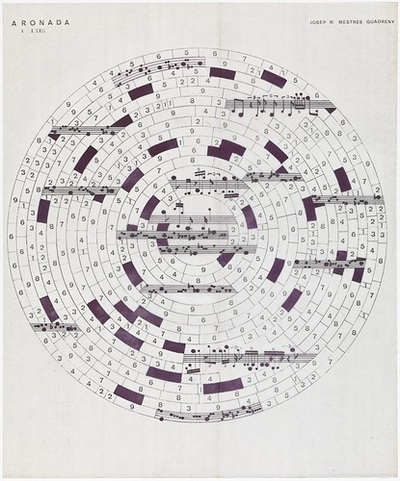

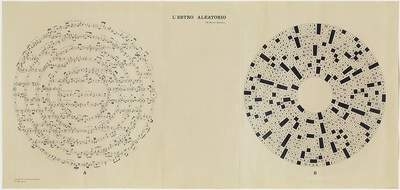

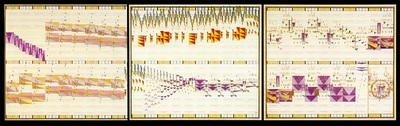

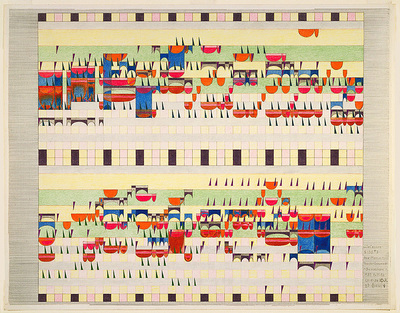

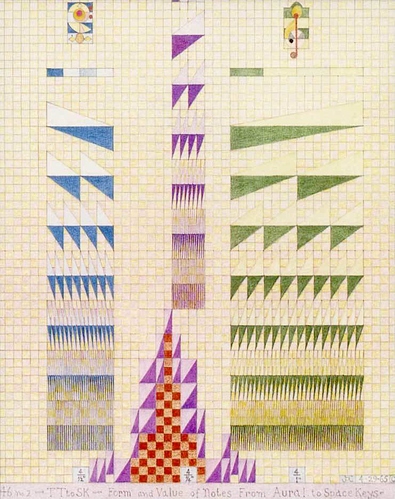

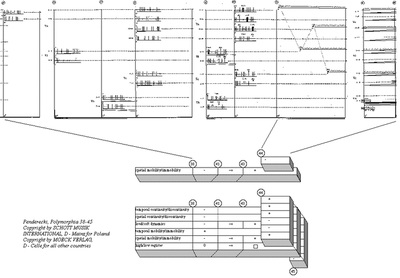

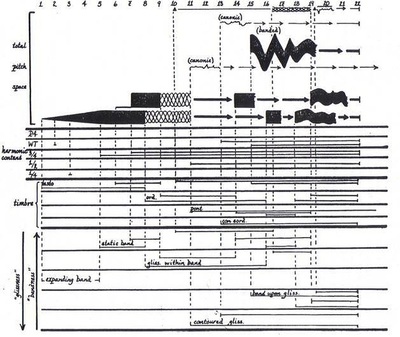

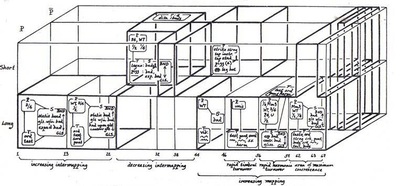

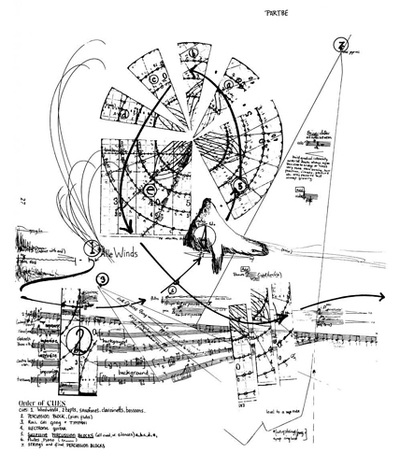

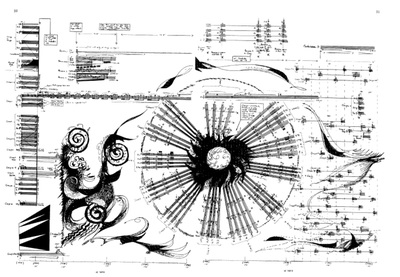

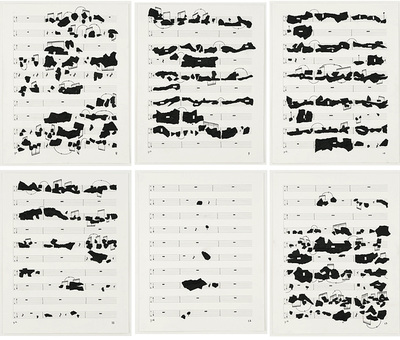

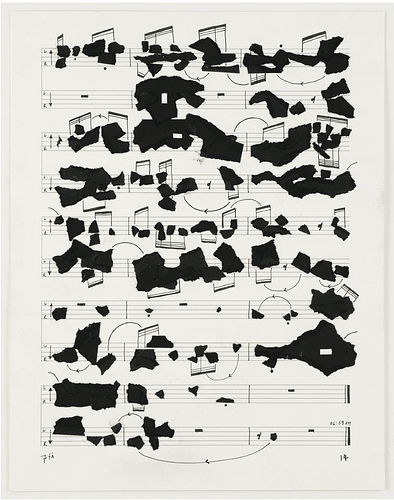

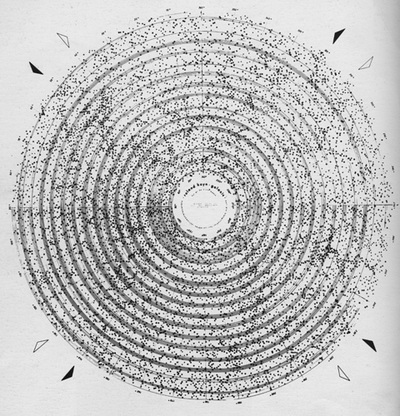

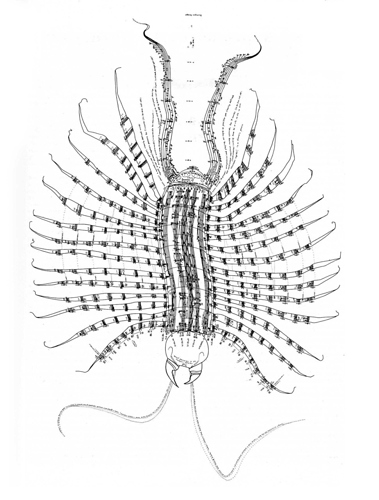

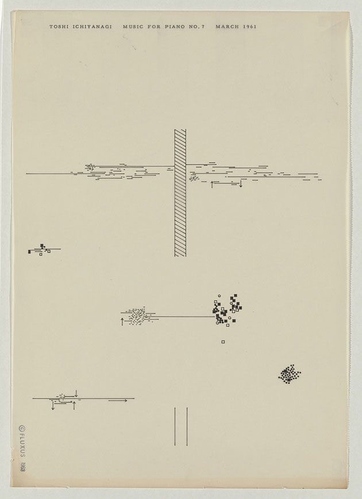

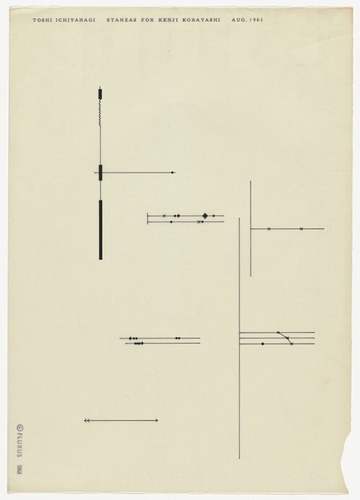

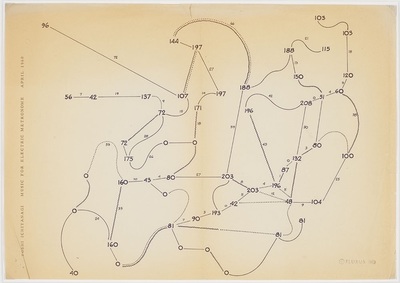

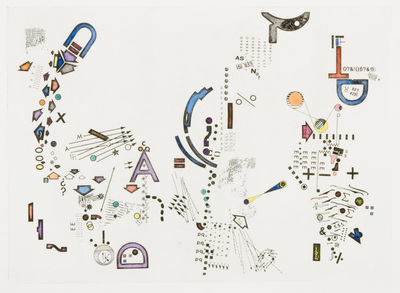

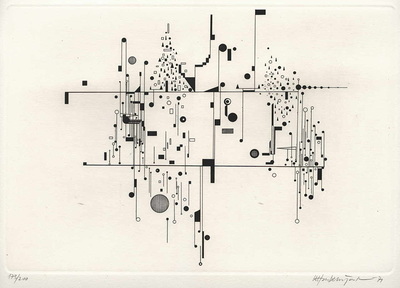

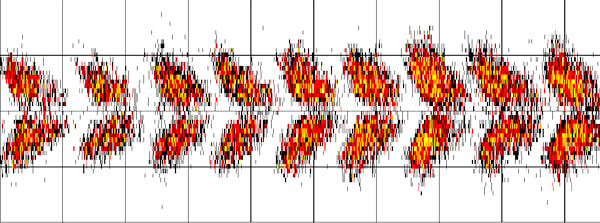

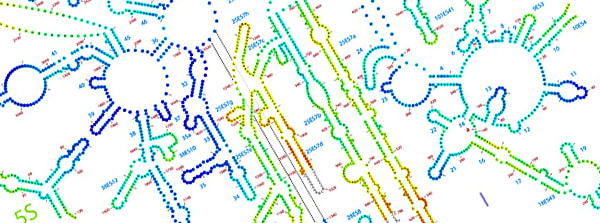

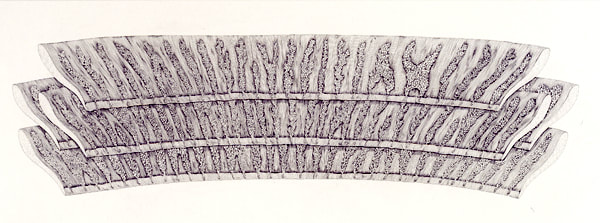

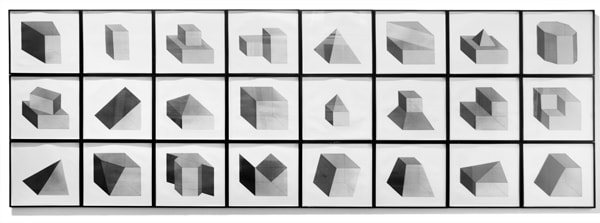

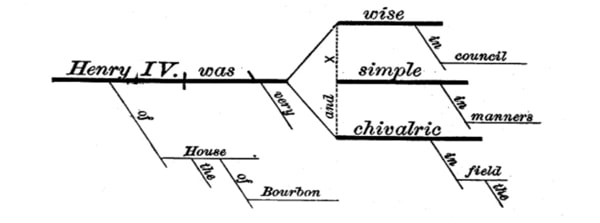

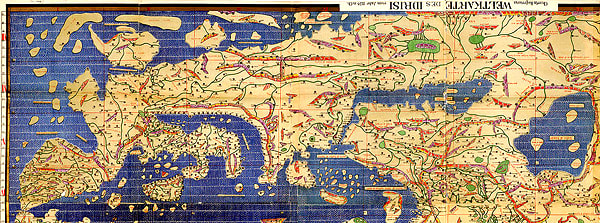

❉ This is the fifth in a series of blogs that discuss diagrams in the arts and sciences. I recently completed my PhD on this subject at Kyoto city University of the Arts, Japan's oldest Art School. Feel free to leave comments or to contact me directly if you'd like any more information on life as an artist in Japan, what a PhD in Fine Art involves, applying for the Japanese Government Monbusho Scholarship program (MEXT), or to talk about diagrams and diagrammatic art in general. In the spring of 1989, the late, great Umberto Eco published his influential book 'Opera Aperta', later translated into English as 'The Open Work'. Within it Eco proposes the concept of semiotic 'openness', as a means to analyse the variety of ways in which artists, composers and writers incorporate chance, ambiguity and multiplicity of meaning in to their work. This deliberate incorporation of chance with in the creative act, Eco argues, marks the boundary between the pre-modern and modern eras within each genre. In his words, "... a classical composition, whether it be a Bach fugue, Verdi's Aida, or Stravinsky's Rite of Spring, posits an assemblage of sound units which the composer arranged in a closed, well-defined manner before presenting it to the listener. He converted his idea into conventional symbols which more or less oblige the eventual performer to reproduce the format devised by the composer himself, whereas the new musical works referred to above reject the definitive, concluded message and multiply the formal possibilities of the distribution of their elements." (1) Figure 1: Igor Stravinsky's hand written manuscript for The Right of Spring, 1913, written in the established musical notation of the time Rather than continue to refine traditional systems of music notation toward the impossible goals of lossless information passage (from composer through conductor and musicians to audience member), these modern composers fully embraced the multiplicity of possible readings and different interpretations at each stage of the process. Eco chose several exemplars of his theory, including important instrumental works by the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007), the Italian composer Luciano Berio (1925-2003), and Belgian and French composers Henri Pousseur (1929-2009) and Pierre Boulez (1925-2016). The scores that he chose had been deliberately devised in order to leave key parts of their musical arrangements open to chance and alteration by others, revealing the inherently creative nature of roles played by conductors and musicians as translators of musical codes, and highlighting the role of individual audience members as interpreters. Figure 2: Luciano Berio, Sincronie, sketch showing the general articulation of the composition for string quartet, 1964. To Eco, creators of open works "...are linked by a common feature: the considerable autonomy left to the individual performer in the way he chooses to play the work. Thus, he is not merely free to interpret the composer's instructions following his own discretion (which in fact happens in traditional music), but he must impose his judgment on the form of the piece, as when he decides how long to hold a note or in what order to group the sounds: all this amounts to an act of improvised creation." (2) Rather than relying upon the standard, dictionary like, 'one-to-one' symbolic systems of traditional musical scores (aimed at accurate reproducibility), these composers were creating scores which acted more like the interconnected network of an encyclopedia's reference systems. Such manuscripts were no longer designed to be read from from left to right and top to bottom, but instead behaved as rhizomatic networks, from which music arrises as an unpredictable emergent phenomenon. Figure 3: Karlheinz Stockhausen, COSMIC PULSES, 8-Channel Surround Sound Electronic Music, 2006-2007 (© www.karlheinzstockhausen.org) In their most extreme forms, readers or users of such manuscripts are guided deeper and deeper within a semi-chaotic systems of meaning that is allowed to both cross and self reference, making the creation of music one of improvised collaboration between composer, conductor, musician and is some cases even the audience. A prolific creator of dense, theory laden graphic scores was the Greek-French avant-garde composer and musical theorist Iannis Xenakis (1922–2001). Having first trained as a civil engineer and later as an architect, Xenakis was proficient in the creation and use of diagrams, and even incorporated mathematical models in to his music in the form of set theory, game theory and stochastic processes. Figure 4: Iannis Xenakis, Terretektorh, Distribution of Musicians, 1965, Ink on paper. Courtesy of the Iannis Xenakis Archives, Bibliothèque nationale de France. Another master of diagrammatic notation was the British experimental composer Cornelius Cardew (1936-1981). Early on in his career Cardew worked for 3 years as an assistant to Karlheinz Stockhausen, as well as assisting at concerts by John Cage and David Tudor where he was introduced to the concept of musical indeterminacy. Between 1963 and 1967 Cardew worked on his monumental graphic score titled 'Treatise', in reference to the work of the german philosopher and mystical logician Ludwig Wittgenstein. Cardew's Treatise takes the form of 193 pages of beautifully crafted diagrammatic structures with no instruction as to how they should to be interpreted by performers, how many performers there should be, or even which instruments should be used. Cardew does suggests however that there should be a pre-emptive collaborative meeting before each performance. Figure 5: Selected pages from Treatise by Cornelius Cardew, 1963-1967, The Upstairs Gallery Press, Buffalo, New York. The video below is an interpretation of the Treatise Score by the Russian contemporary music group KYMATIC ensemble. It was by means of the diagram and the act of diagramming that composers questioned and expanded our very notions of how music is created, transcribed, interpreted and experienced, heralding the dawn of what Eco saw as the true modern period. Below are a selection of graphic scores chosen to highlight the shear range of ambitious and novel diagrammatic techniques from this remarkable period in the history of music. However one of these manuscripts predates the others by over 600 years... References:

1) Umberto Eco, The open work, Translated by Anna Cancogni, Harvard University Press, 1989. p.19. 2) Umberto Eco, Ibid. p.1.

1 Comment

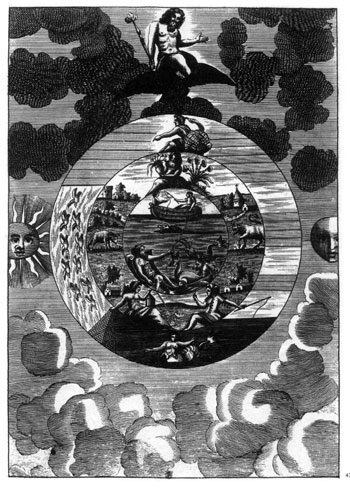

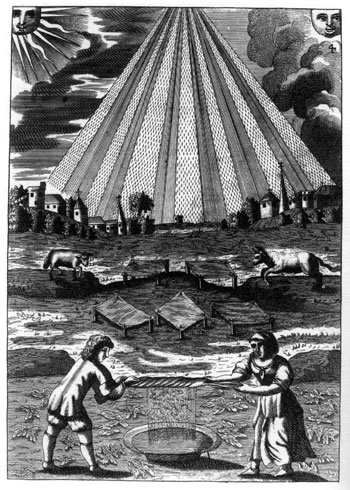

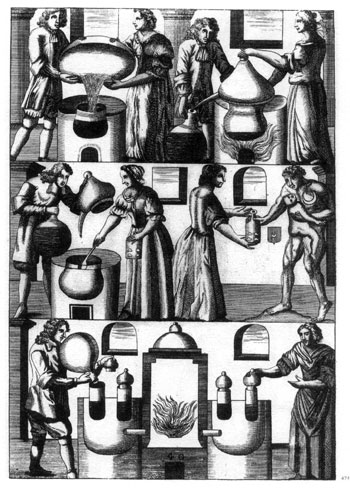

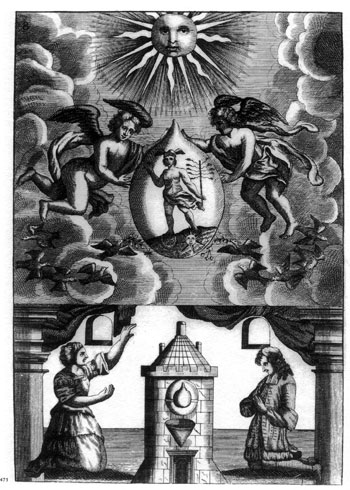

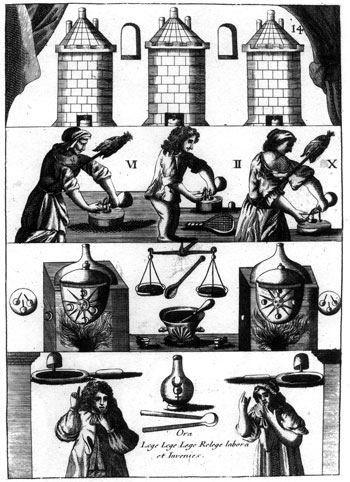

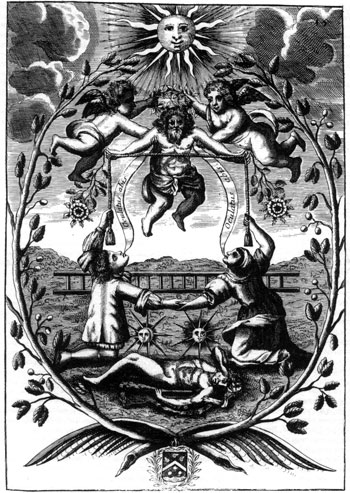

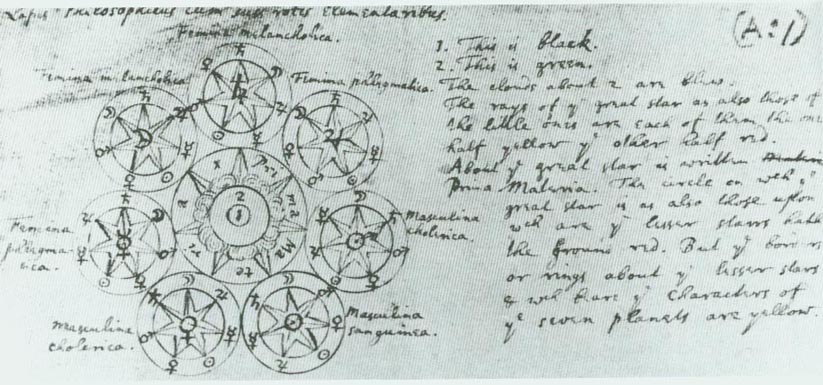

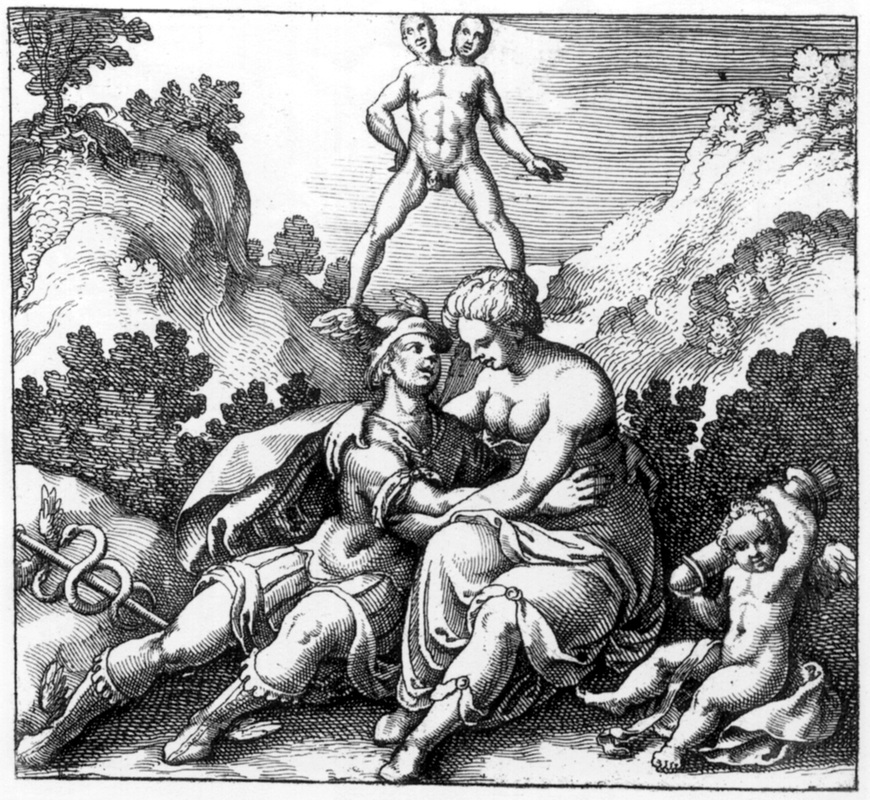

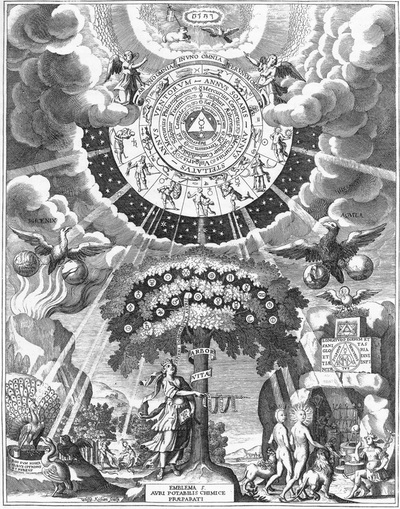

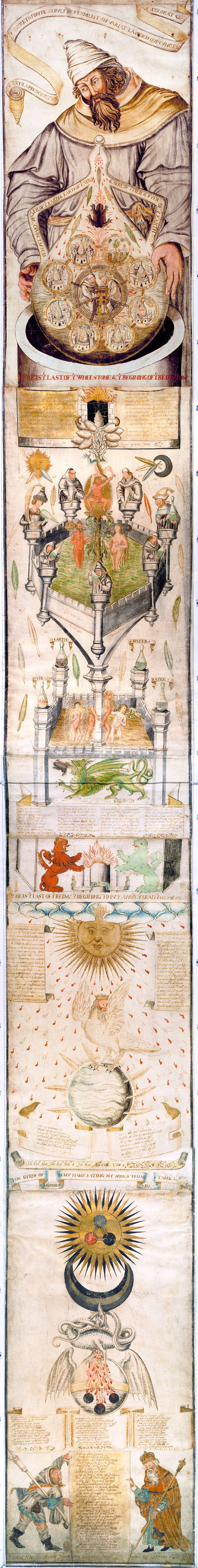

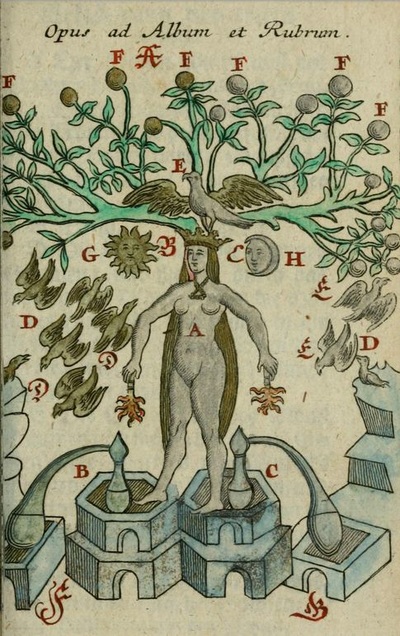

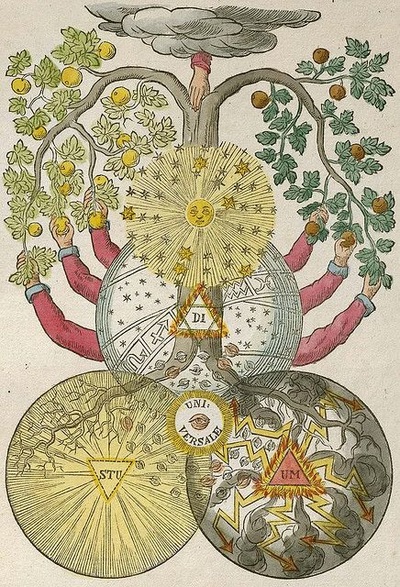

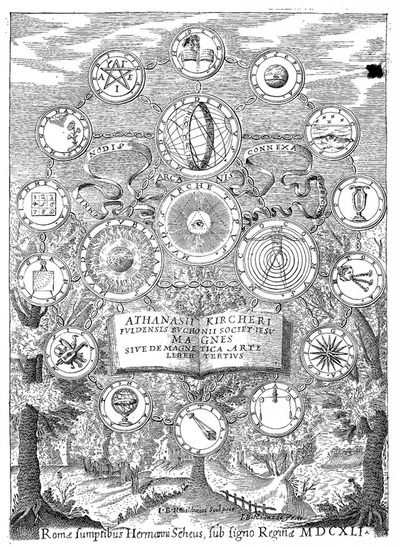

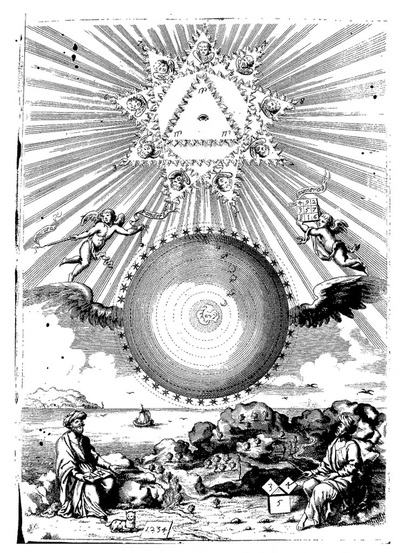

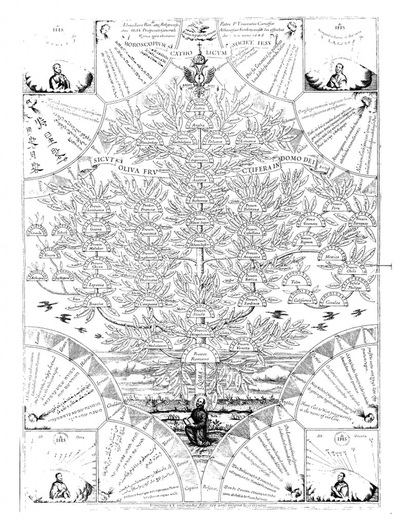

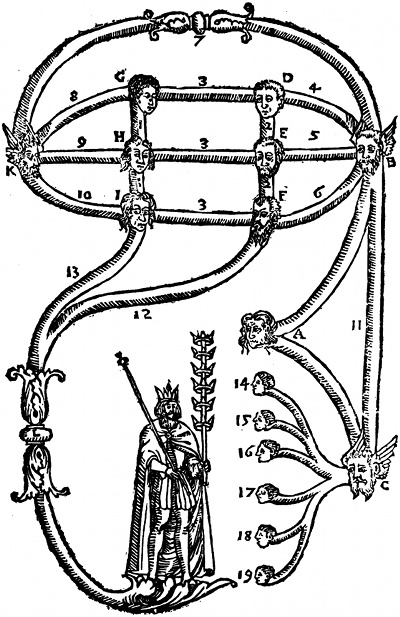

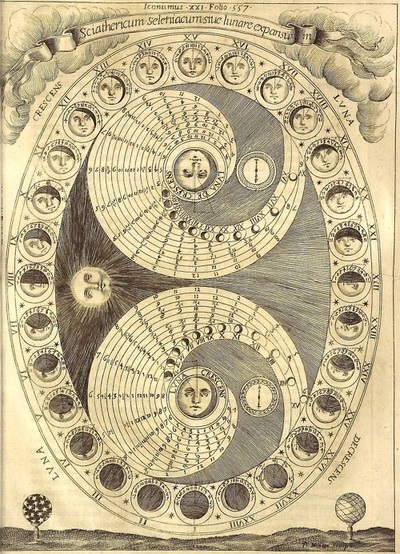

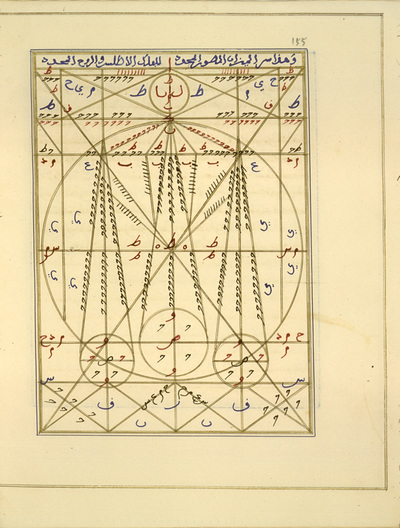

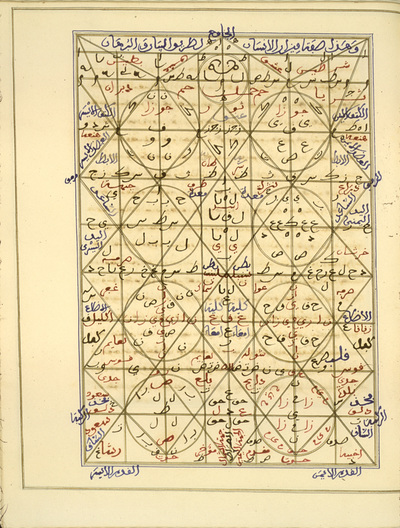

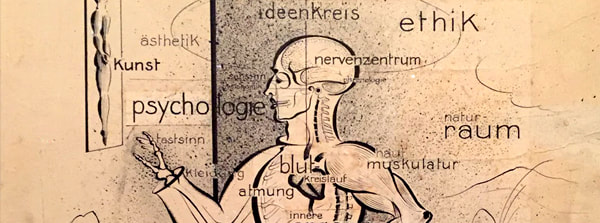

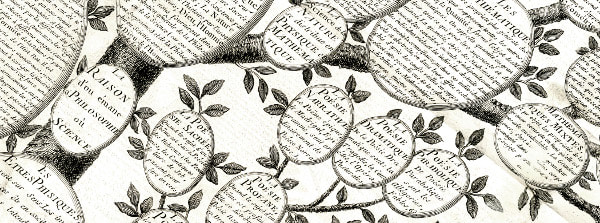

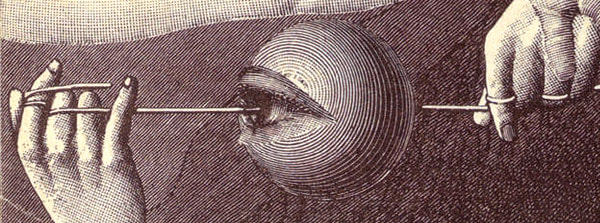

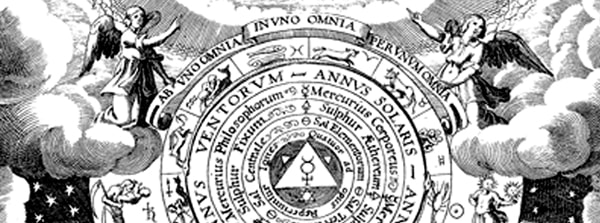

❉ This is the fourth in a series of blogs that discuss diagrams in the arts and sciences. I recently completed my PhD on this subject at Kyoto city University of the Arts, Japan's oldest Art School. Feel free to leave comments or to contact me directly if you'd like any more information on life as an artist in Japan, what a PhD in Fine Art involves, applying for the Japanese Government Monbusho Scholarship program (MEXT), or to talk about diagrams and diagrammatic art in general. The word alchemy has Arabic origins, and like other English 'al' words: algebra, algorithm, albatross and alcohol, they all incorporate the Arabic definite article 'al', meaning 'the', and alchemy is derived from the Arabic word al-kīmiyā’ (الكيمياء) meaning 'the philosophers stone'. However alchemy itself has a rich and convoluted history which predates its Arabic influences, and spans some 4000 years. Similar philosophical systems appear to have arisen independently on three different continents, giving rise to Chinese, Indian and the Western alchemy, the latter of which can be traced from its origins in Greco-Roman Egypt via the Islamic world to Medieval Europe. Figure 1: Matthäus Merian, Tabula Smaragdina (The emerald tablet) first published 1618, Engraving, size unknown. By the end of the middle ages in Europe, Western Alchemy had adopted the diagrammatic format as its medium of choice, and the early fifteenth century witnessed the rapid emergence of the alchemical diagram as a means of codifying, arranging and recording alchemical transmutations. What had previously been a text dominated field of allegory, explication and word-play was rapidly overtaken by a panoply of symbolic forms drawn from ancient myth and fable. Alchemical artists worked to create intricate networks of obtuse symbols as landscapes, all of which reference alchemy's rich, international, cultural history. The qualities of the diagram were perfectly suited to an alchemical arts that stressed the fluid nature of both concept and form, and did so in a style of learned authority and secrecy. Over the following two centuries the success of alchemical diagrams meant that they no longer merely punctuated alchemical texts but were compiled in to series in their own right, to depict the principles governing the discipline. Text became relegated to title, label and caption, and certain alchemical treatise such as The Silent Book (Mutus Liber, La Rochelle, 1677) were composed entirely of emblematic images, diagrammatically outlining the processes involved in manufacturing the philosophers stone, the base matter from which all other materials could be created. Figure 2: Selected plates from Mutus Liber, first published in 1677. The authors name was given as Altus, a pseudonym. No less a figure than Isaac Newton devoted a great deal of his time to the study of alchemy, amassing a collection of 169 books on the topic within his personal library, as well as leaving behind hundreds of his own unpublished notes relating to the subject. In 1942 the economist John Maynard Keynes purchased and studied a large number of Newton's papers, leading him to proclaim that "Newton was not the first of the age of reason, he was the last of the magicians". Fig. 3: Isaac Newton (1643 - 1723), copy of a diagram of the Philosopher's Stone, the Holy Grail of alchemy ( Grace K. Babson Collection of the Works of Sir Isaac Newton on permanent deposit at the Dibner Institute and Burndy Library, Cambridge, Massachusetts ) The diagrams of alchemy are a chaotic system of references and a constantly changing matrix of symbols and code names for arcane substances and experiments. According to the motto of the Rosicrucian Michael Maier, the goal of alchemy was “to reach the intellect via the senses”, as depicted by the motif of the hermaphrodite. Figure 4: Michael Maiers, emblem plate number 38, Atalanta Fugiens, 1617 This figure represents a mix of sensual stimulus (Aphrodite) and intellectual appeal (Hermes), an approach aiming to provoke man’s intuitive insights in to the essential connections, rather than his discursive ability, which was largely held to be a destructive force. This is an interesting reversal of the base premise of my 2014 thesis 'Romantic Objectivism', which proposes that modern and contemporary diagrammatic art attempts to reach the senses via the intellect, or rather the subjective via the objective visual language of science. The goal, however, of triggering intuitive insights in to deep and essential connections remains the same. The transmutations of alchemy are said to occur in both the external world of matter and the internal psychological world of the psyche. The Swiss psychiatrist and psychotherapist C.G. Jung proposed that “The alchemical operations were real, only this reality was not physical but psychological. Alchemy represents the projection of a drama both cosmic and spiritual in laboratory terms. The opus magnum [“great work”] had two aims: the rescue of the human soul, and the salvation of the cosmos.” This was alchemy on a grand and ambitious scale, and European alchemy marks the start of an explosive growth of diagram production in the west, driven by a human desire to create meaning and order within our shared and subjective experience of reality. Kjell Hellesøe's translation of a 20th century French commentary on the Mutus Liber can be found here: http://hermetic.com/caduceus/articles/1/3/mutus-liber.html |

Dr. Michael WhittleBritish artist and Posts:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|