|

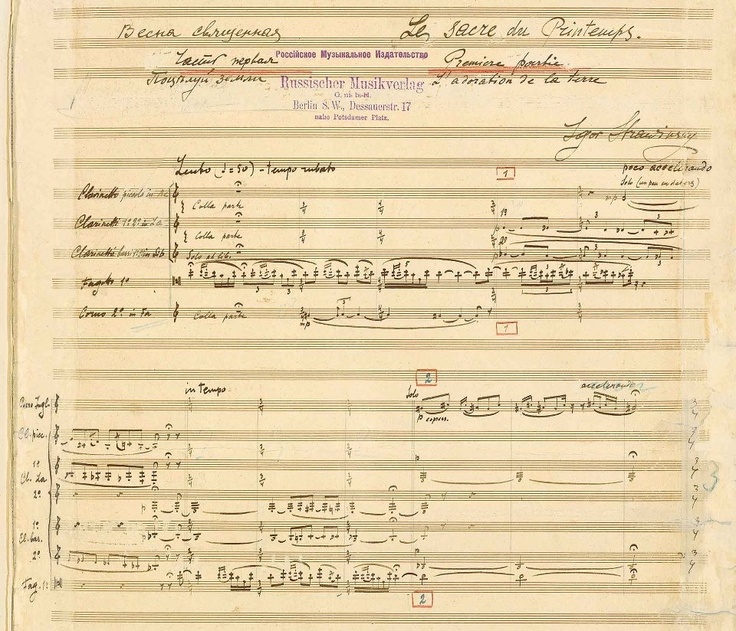

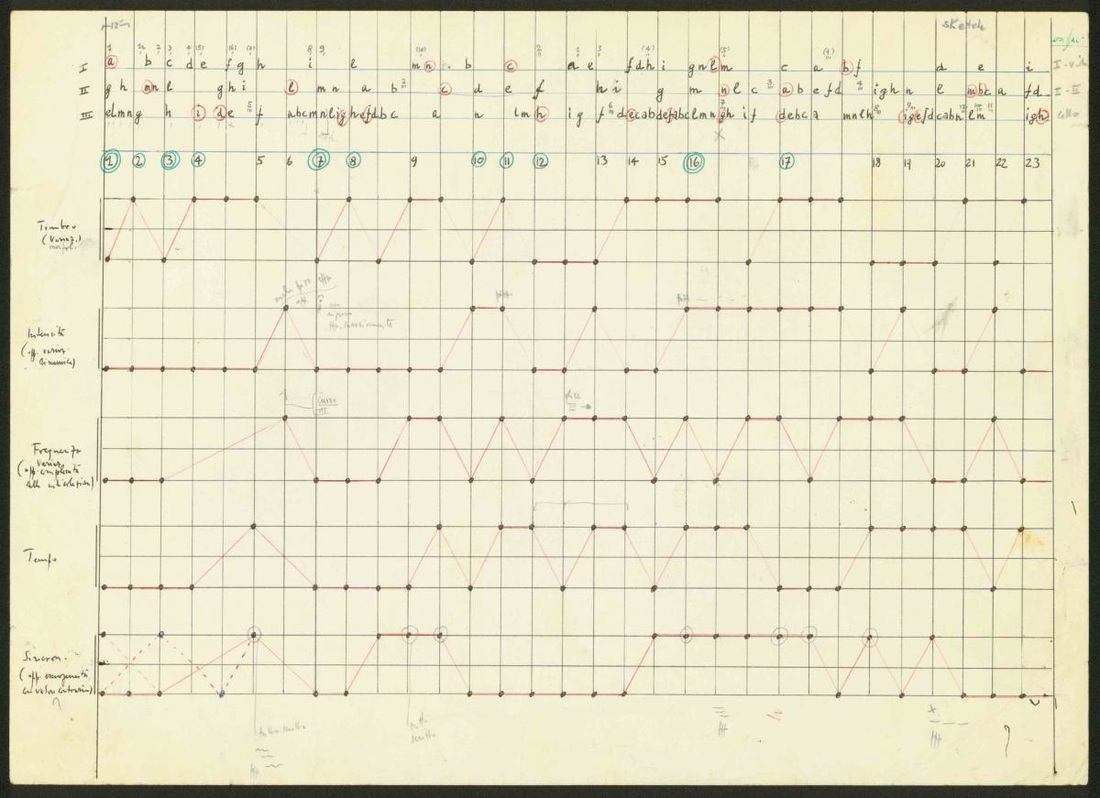

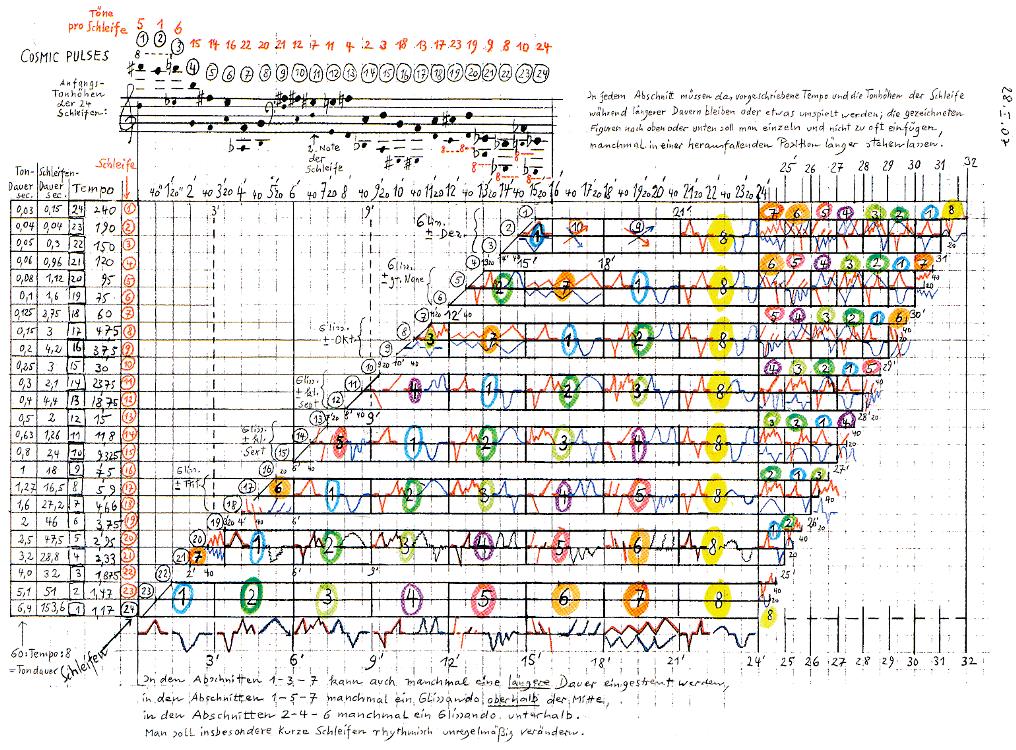

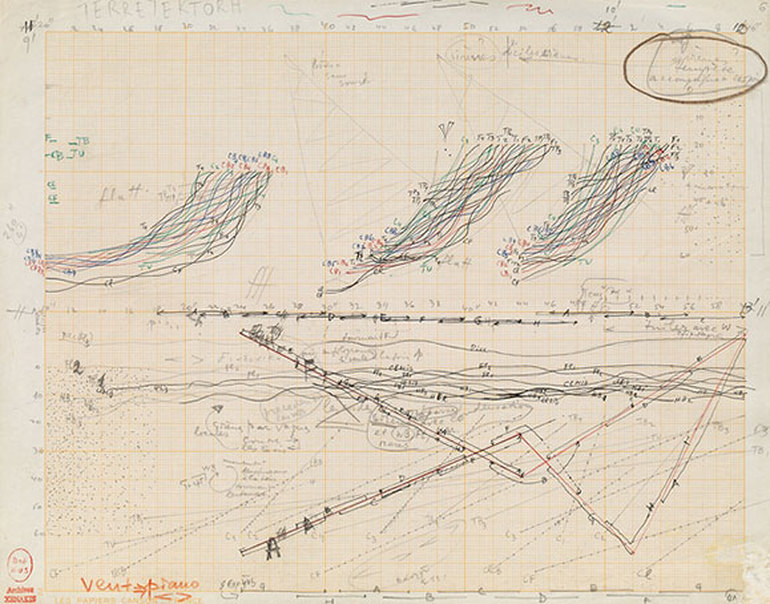

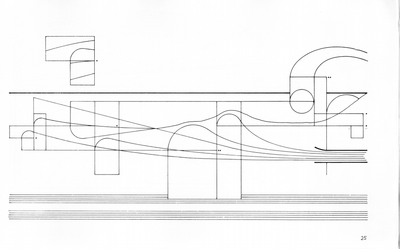

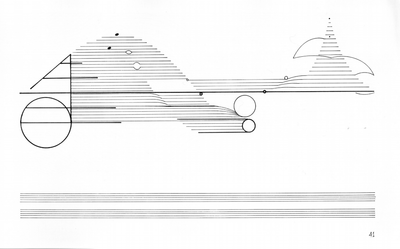

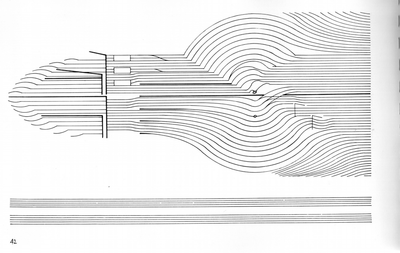

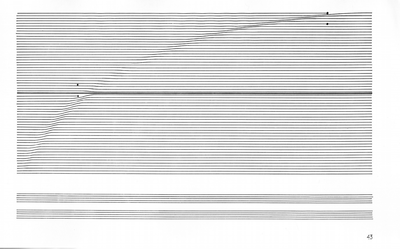

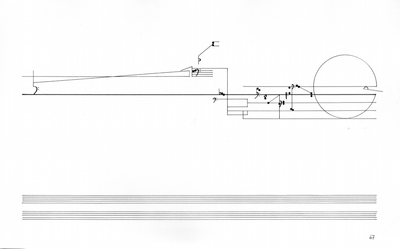

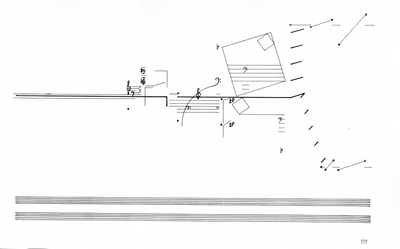

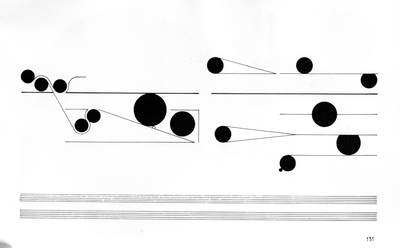

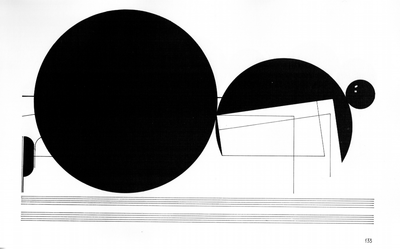

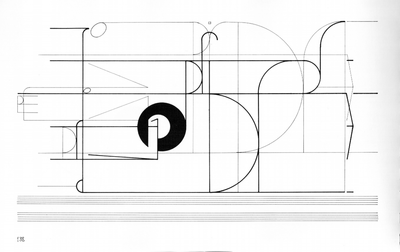

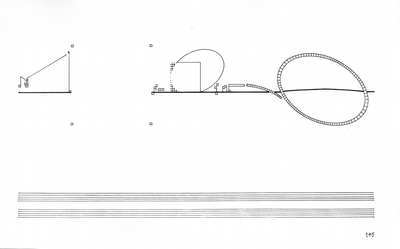

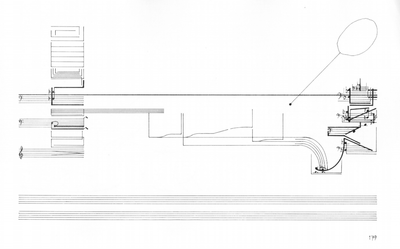

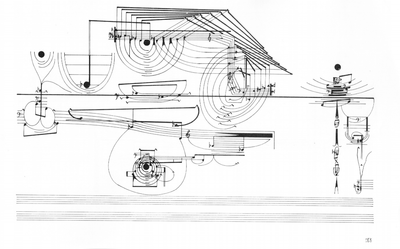

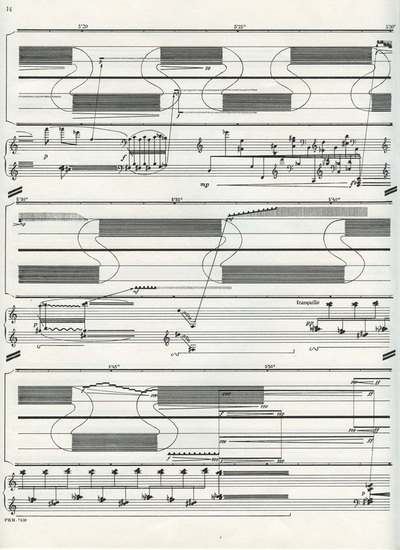

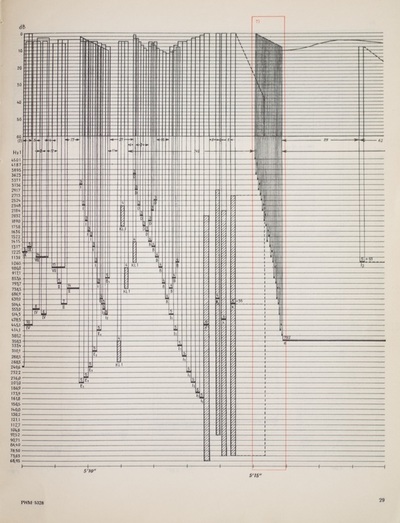

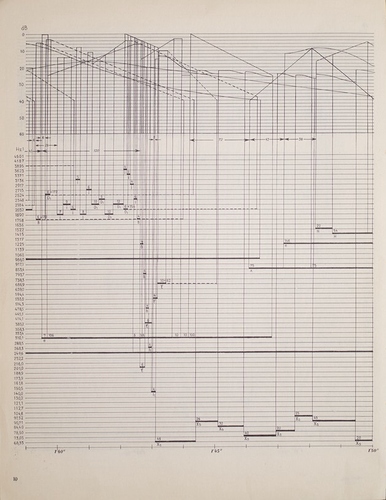

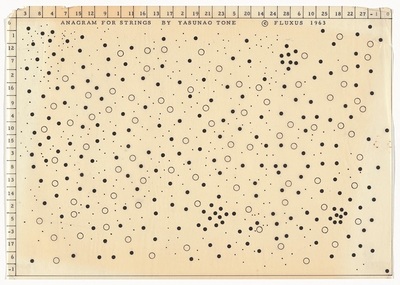

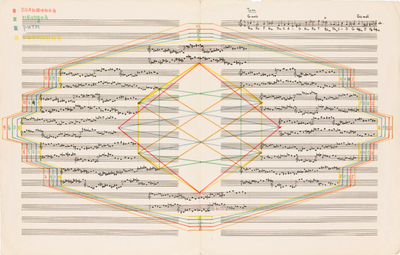

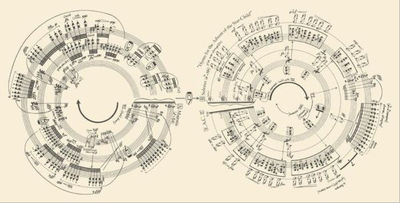

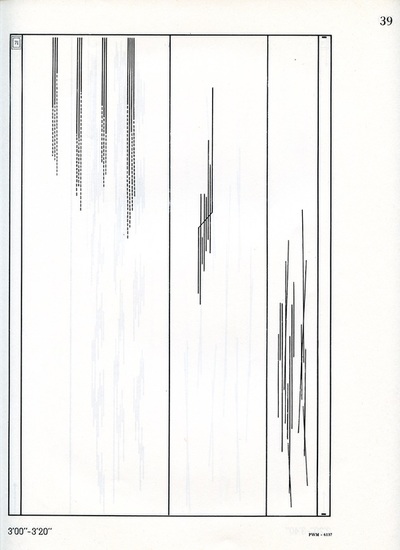

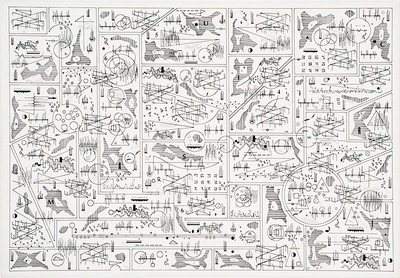

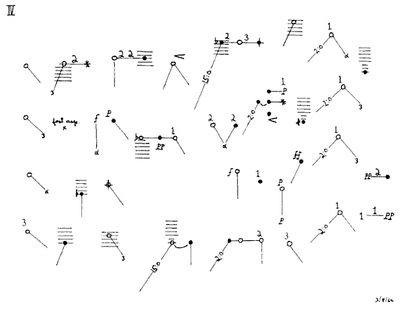

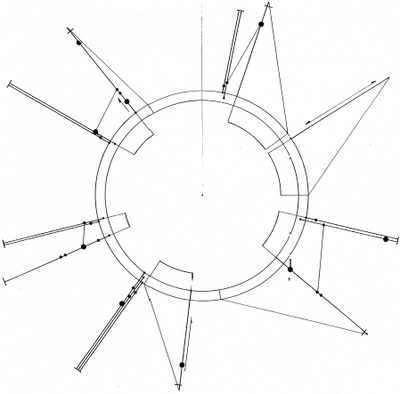

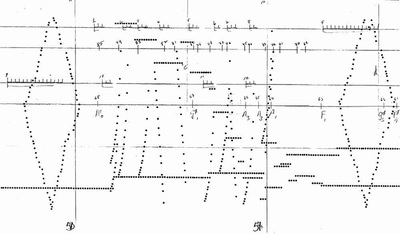

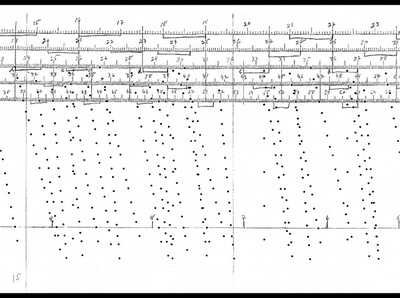

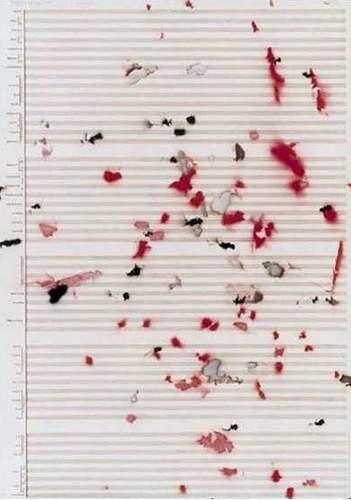

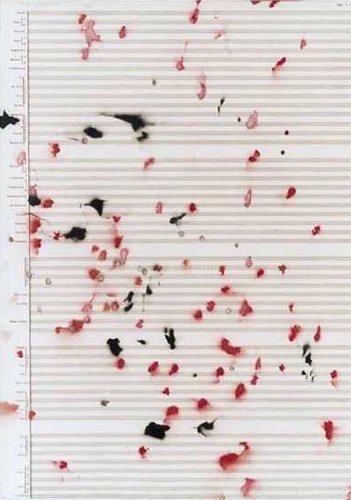

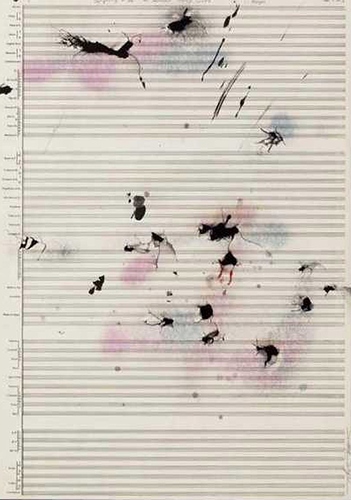

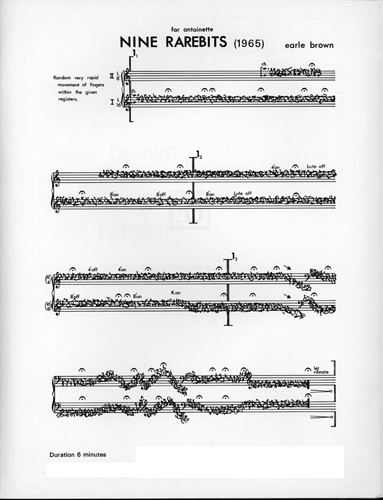

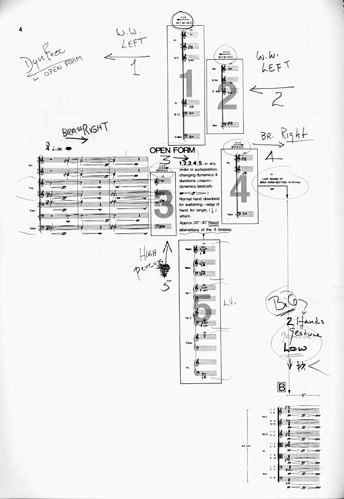

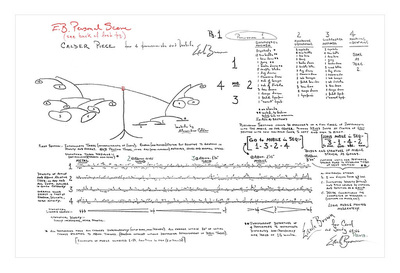

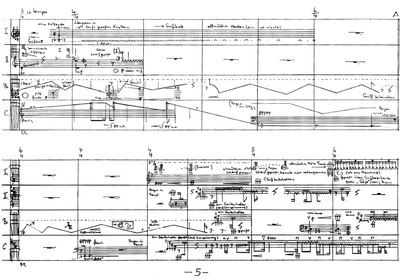

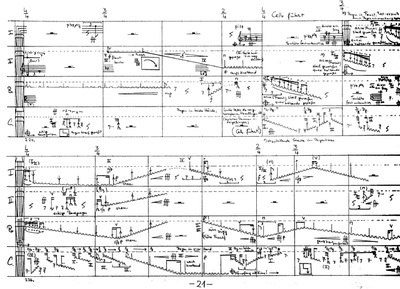

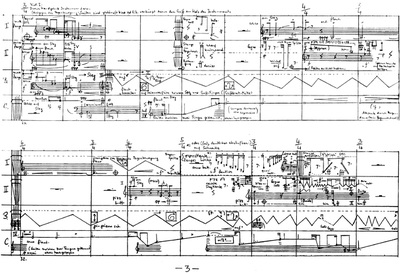

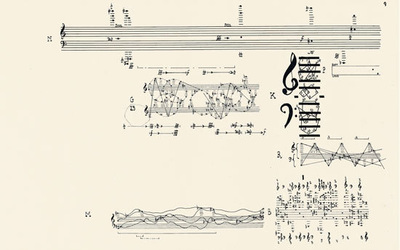

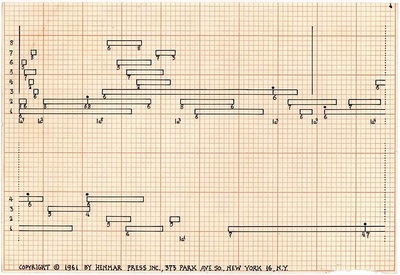

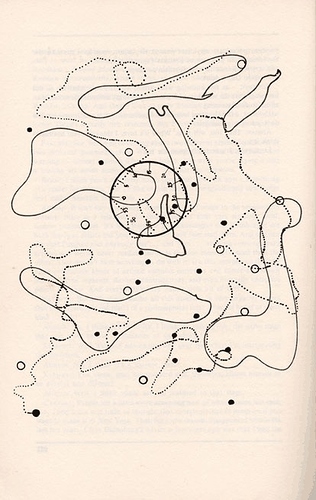

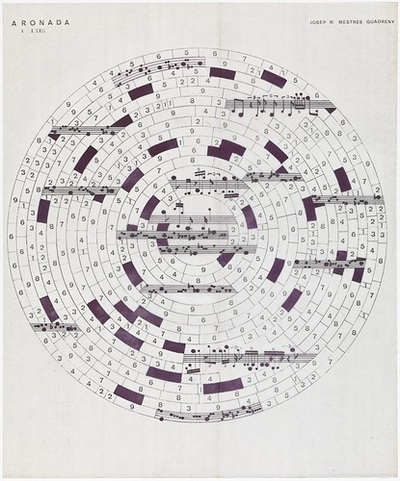

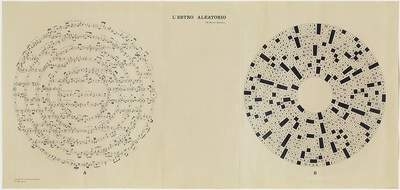

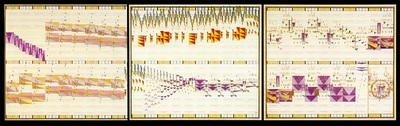

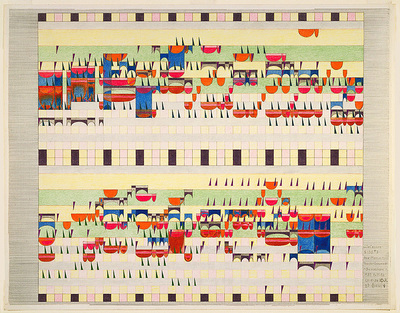

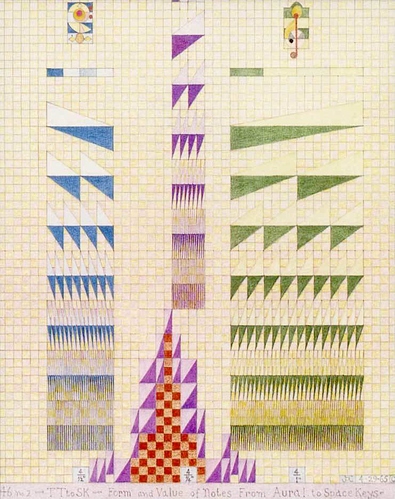

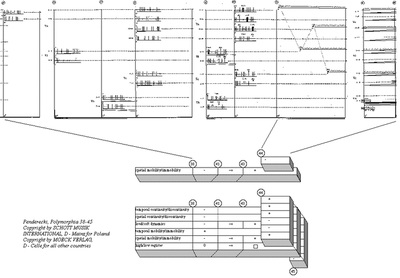

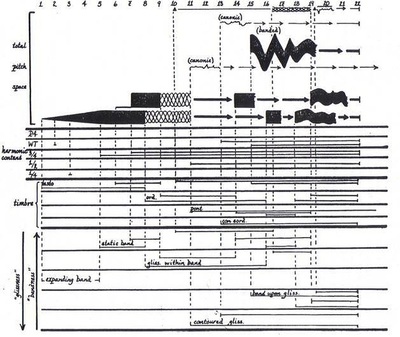

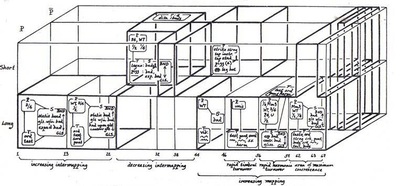

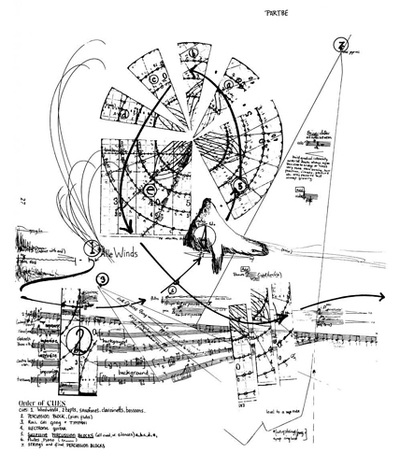

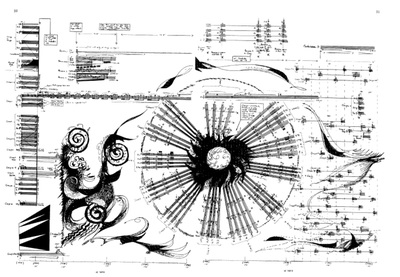

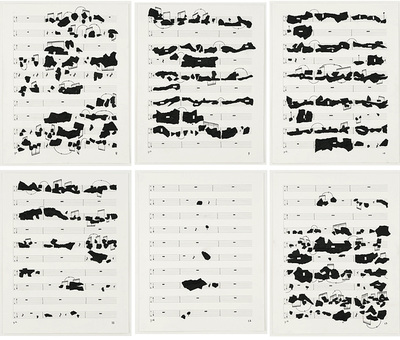

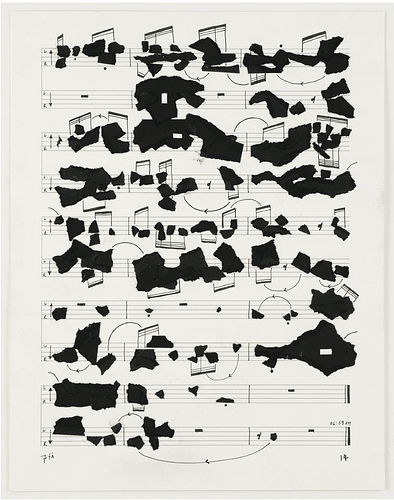

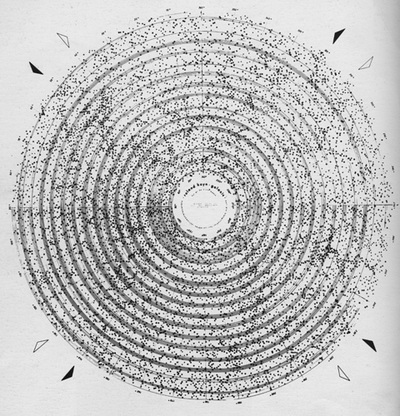

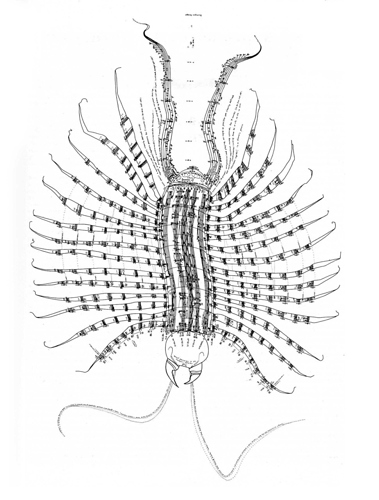

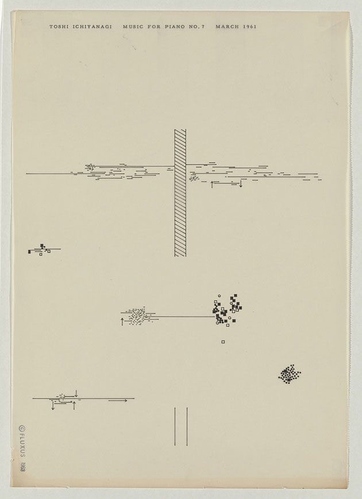

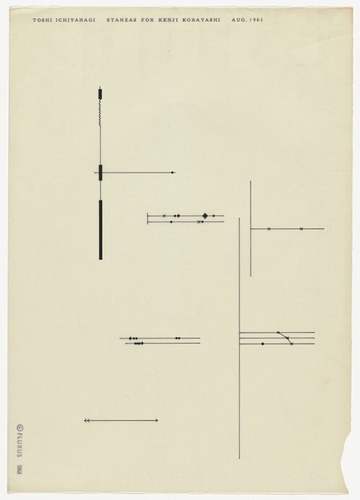

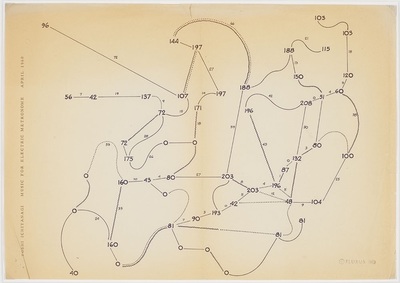

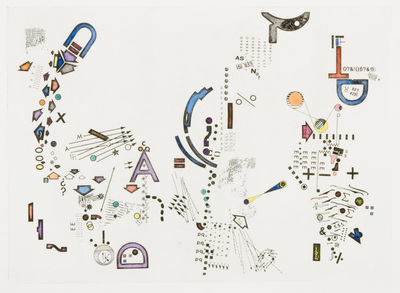

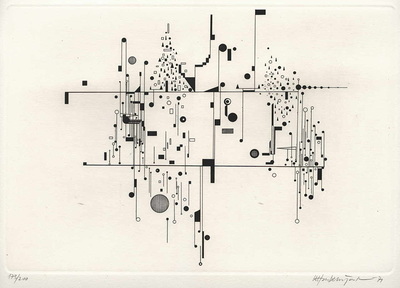

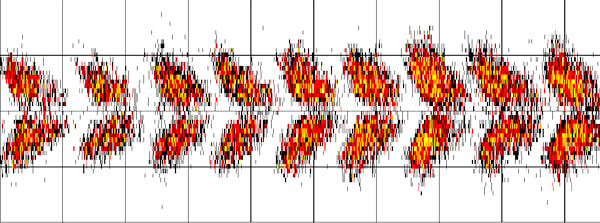

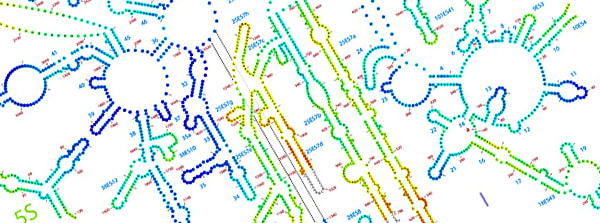

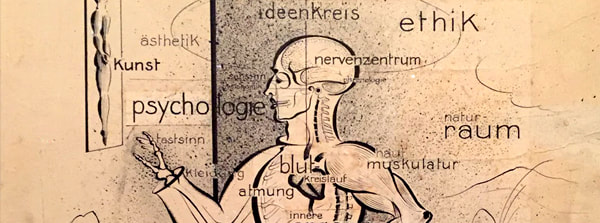

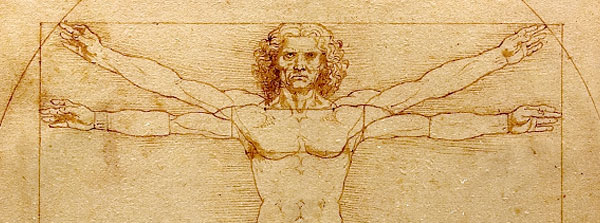

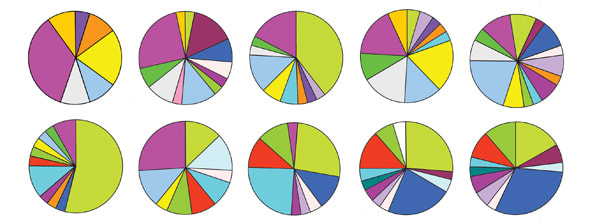

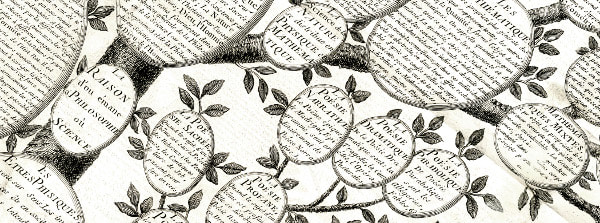

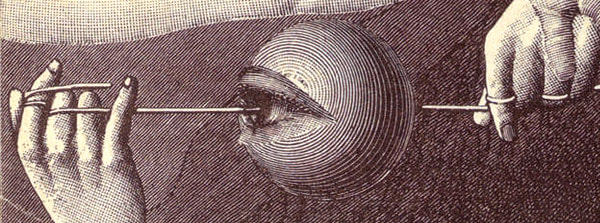

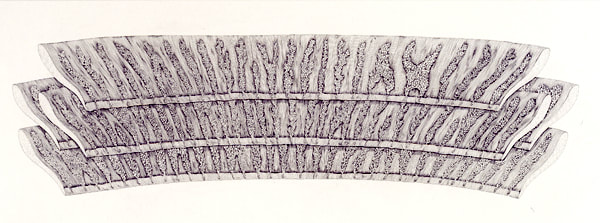

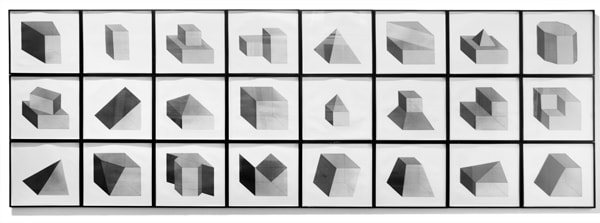

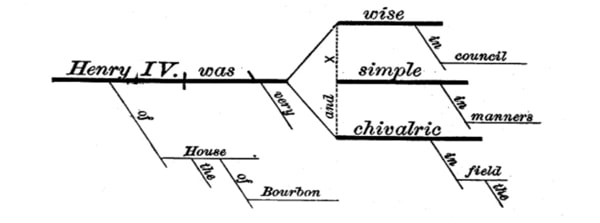

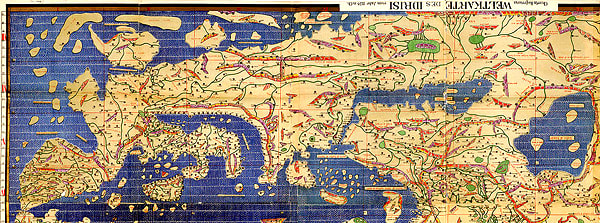

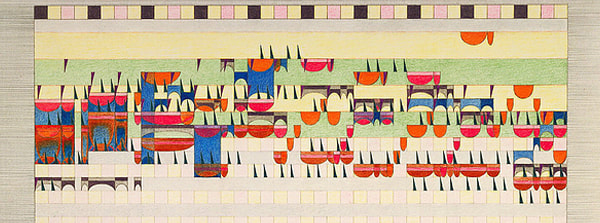

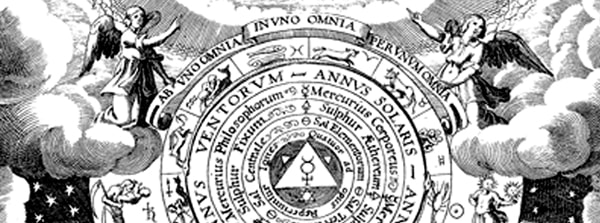

❉ This is the fifth in a series of blogs that discuss diagrams in the arts and sciences. I recently completed my PhD on this subject at Kyoto city University of the Arts, Japan's oldest Art School. Feel free to leave comments or to contact me directly if you'd like any more information on life as an artist in Japan, what a PhD in Fine Art involves, applying for the Japanese Government Monbusho Scholarship program (MEXT), or to talk about diagrams and diagrammatic art in general. In the spring of 1989, the late, great Umberto Eco published his influential book 'Opera Aperta', later translated into English as 'The Open Work'. Within it Eco proposes the concept of semiotic 'openness', as a means to analyse the variety of ways in which artists, composers and writers incorporate chance, ambiguity and multiplicity of meaning in to their work. This deliberate incorporation of chance with in the creative act, Eco argues, marks the boundary between the pre-modern and modern eras within each genre. In his words, "... a classical composition, whether it be a Bach fugue, Verdi's Aida, or Stravinsky's Rite of Spring, posits an assemblage of sound units which the composer arranged in a closed, well-defined manner before presenting it to the listener. He converted his idea into conventional symbols which more or less oblige the eventual performer to reproduce the format devised by the composer himself, whereas the new musical works referred to above reject the definitive, concluded message and multiply the formal possibilities of the distribution of their elements." (1) Figure 1: Igor Stravinsky's hand written manuscript for The Right of Spring, 1913, written in the established musical notation of the time Rather than continue to refine traditional systems of music notation toward the impossible goals of lossless information passage (from composer through conductor and musicians to audience member), these modern composers fully embraced the multiplicity of possible readings and different interpretations at each stage of the process. Eco chose several exemplars of his theory, including important instrumental works by the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007), the Italian composer Luciano Berio (1925-2003), and Belgian and French composers Henri Pousseur (1929-2009) and Pierre Boulez (1925-2016). The scores that he chose had been deliberately devised in order to leave key parts of their musical arrangements open to chance and alteration by others, revealing the inherently creative nature of roles played by conductors and musicians as translators of musical codes, and highlighting the role of individual audience members as interpreters. Figure 2: Luciano Berio, Sincronie, sketch showing the general articulation of the composition for string quartet, 1964. To Eco, creators of open works "...are linked by a common feature: the considerable autonomy left to the individual performer in the way he chooses to play the work. Thus, he is not merely free to interpret the composer's instructions following his own discretion (which in fact happens in traditional music), but he must impose his judgment on the form of the piece, as when he decides how long to hold a note or in what order to group the sounds: all this amounts to an act of improvised creation." (2) Rather than relying upon the standard, dictionary like, 'one-to-one' symbolic systems of traditional musical scores (aimed at accurate reproducibility), these composers were creating scores which acted more like the interconnected network of an encyclopedia's reference systems. Such manuscripts were no longer designed to be read from from left to right and top to bottom, but instead behaved as rhizomatic networks, from which music arrises as an unpredictable emergent phenomenon. Figure 3: Karlheinz Stockhausen, COSMIC PULSES, 8-Channel Surround Sound Electronic Music, 2006-2007 (© www.karlheinzstockhausen.org) In their most extreme forms, readers or users of such manuscripts are guided deeper and deeper within a semi-chaotic systems of meaning that is allowed to both cross and self reference, making the creation of music one of improvised collaboration between composer, conductor, musician and is some cases even the audience. A prolific creator of dense, theory laden graphic scores was the Greek-French avant-garde composer and musical theorist Iannis Xenakis (1922–2001). Having first trained as a civil engineer and later as an architect, Xenakis was proficient in the creation and use of diagrams, and even incorporated mathematical models in to his music in the form of set theory, game theory and stochastic processes. Figure 4: Iannis Xenakis, Terretektorh, Distribution of Musicians, 1965, Ink on paper. Courtesy of the Iannis Xenakis Archives, Bibliothèque nationale de France. Another master of diagrammatic notation was the British experimental composer Cornelius Cardew (1936-1981). Early on in his career Cardew worked for 3 years as an assistant to Karlheinz Stockhausen, as well as assisting at concerts by John Cage and David Tudor where he was introduced to the concept of musical indeterminacy. Between 1963 and 1967 Cardew worked on his monumental graphic score titled 'Treatise', in reference to the work of the german philosopher and mystical logician Ludwig Wittgenstein. Cardew's Treatise takes the form of 193 pages of beautifully crafted diagrammatic structures with no instruction as to how they should to be interpreted by performers, how many performers there should be, or even which instruments should be used. Cardew does suggests however that there should be a pre-emptive collaborative meeting before each performance. Figure 5: Selected pages from Treatise by Cornelius Cardew, 1963-1967, The Upstairs Gallery Press, Buffalo, New York. The video below is an interpretation of the Treatise Score by the Russian contemporary music group KYMATIC ensemble. It was by means of the diagram and the act of diagramming that composers questioned and expanded our very notions of how music is created, transcribed, interpreted and experienced, heralding the dawn of what Eco saw as the true modern period. Below are a selection of graphic scores chosen to highlight the shear range of ambitious and novel diagrammatic techniques from this remarkable period in the history of music. However one of these manuscripts predates the others by over 600 years... References:

1) Umberto Eco, The open work, Translated by Anna Cancogni, Harvard University Press, 1989. p.19. 2) Umberto Eco, Ibid. p.1.

1 Comment

|

Dr. Michael WhittleBritish artist and Posts:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|