|

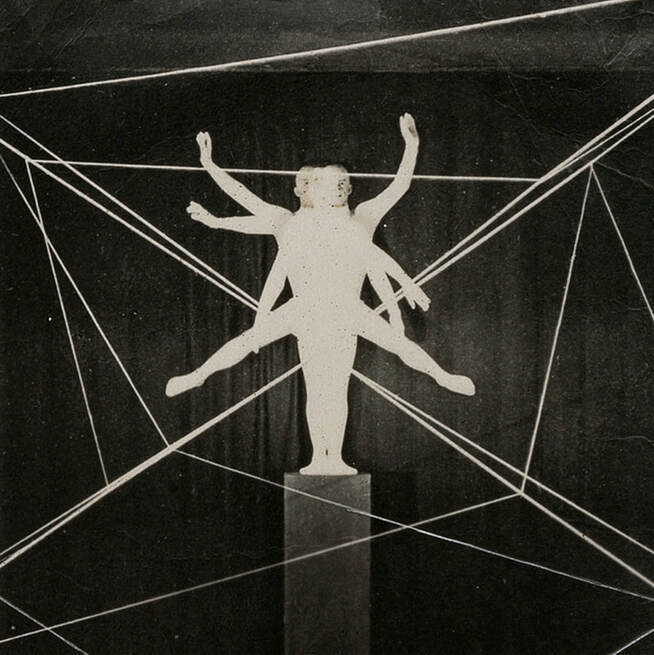

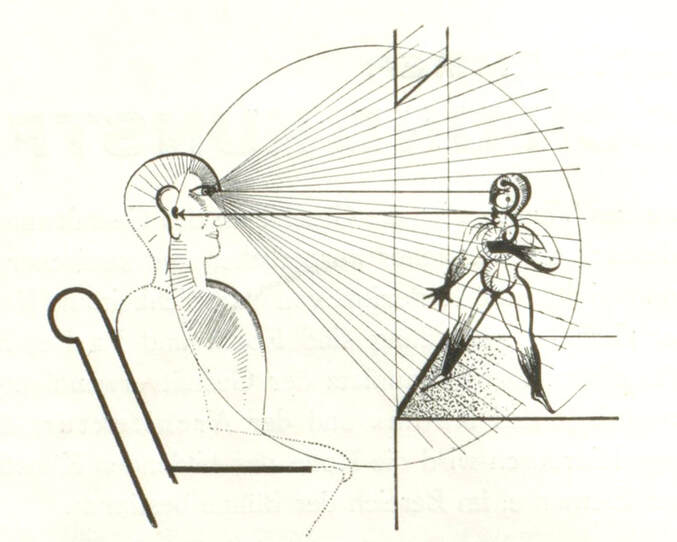

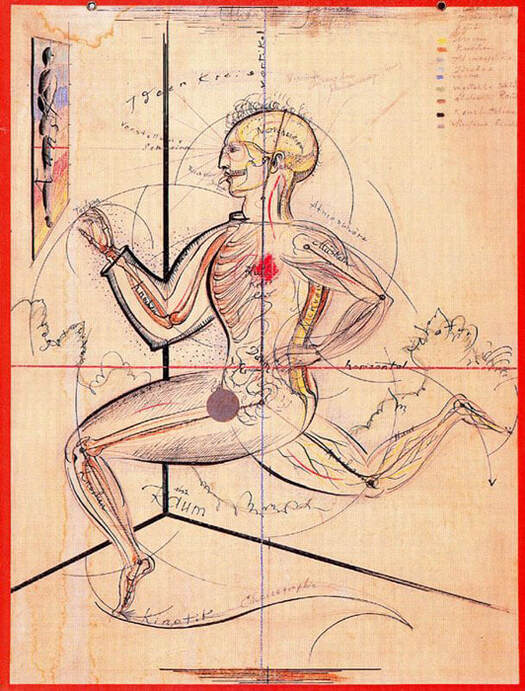

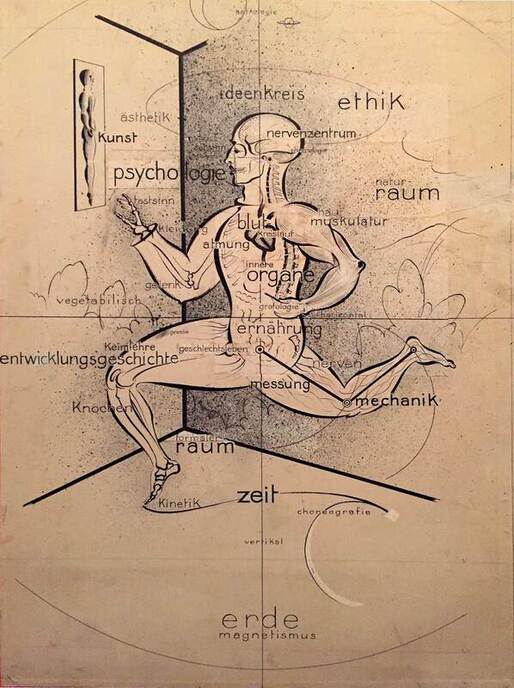

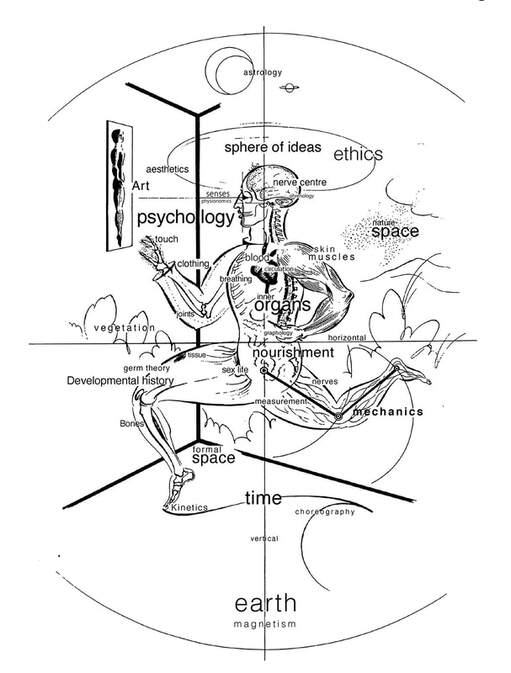

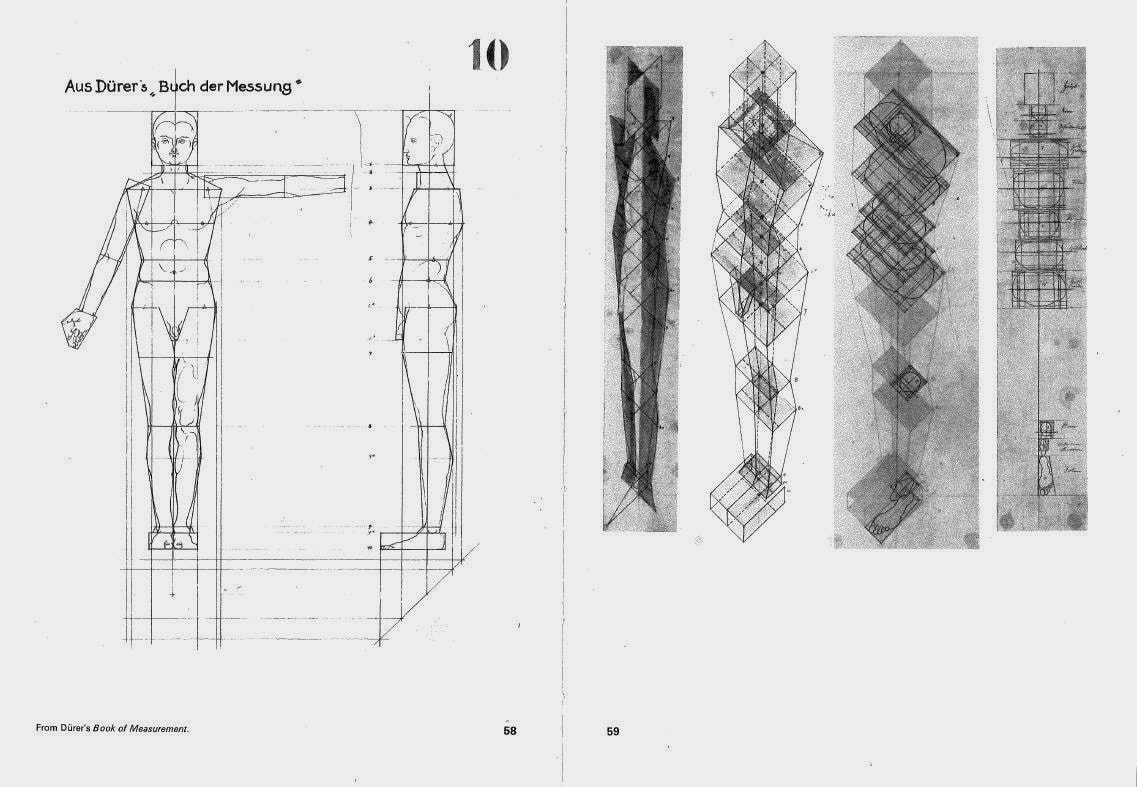

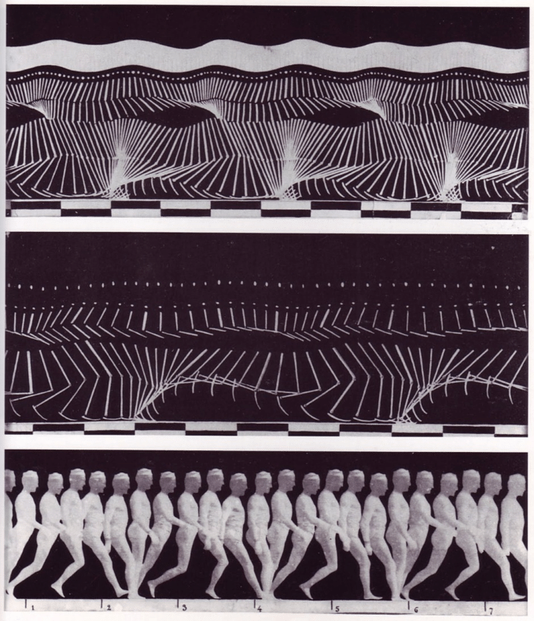

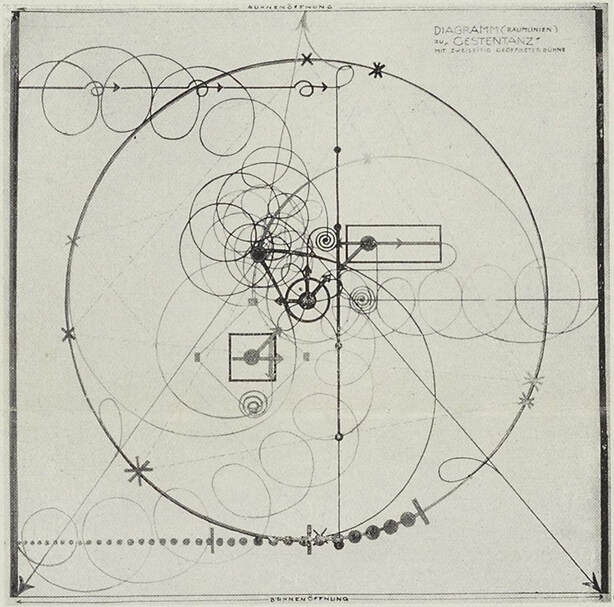

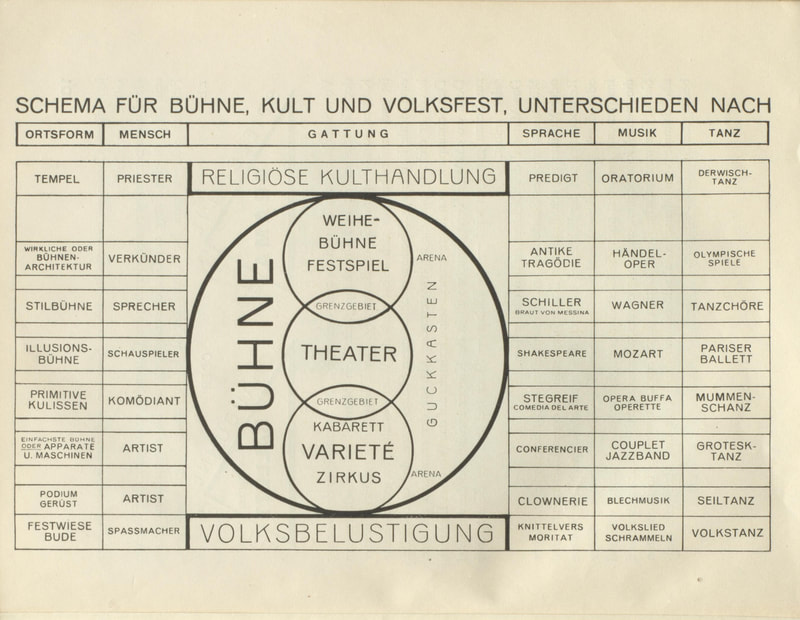

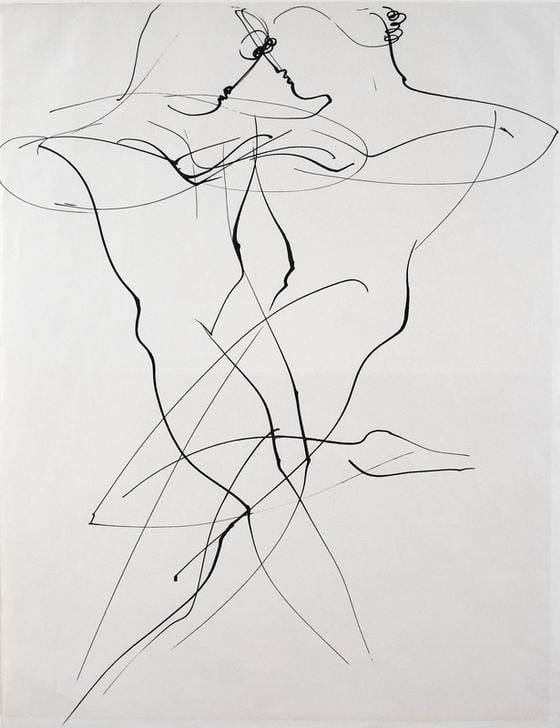

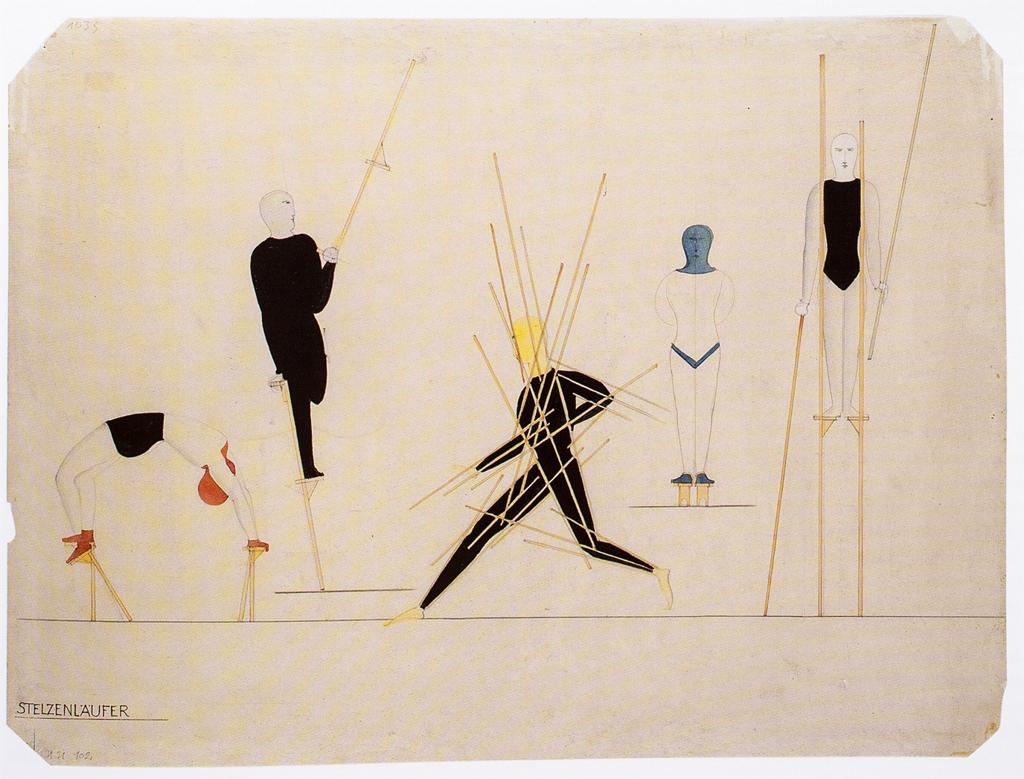

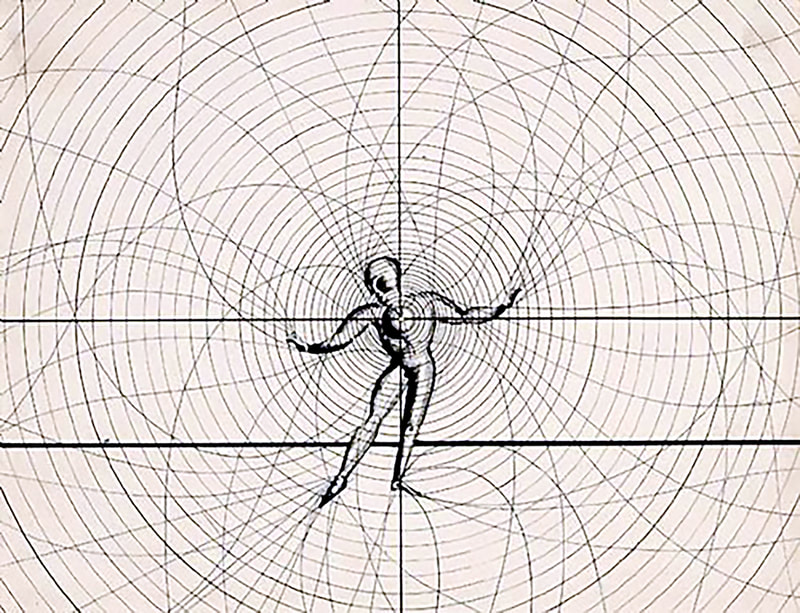

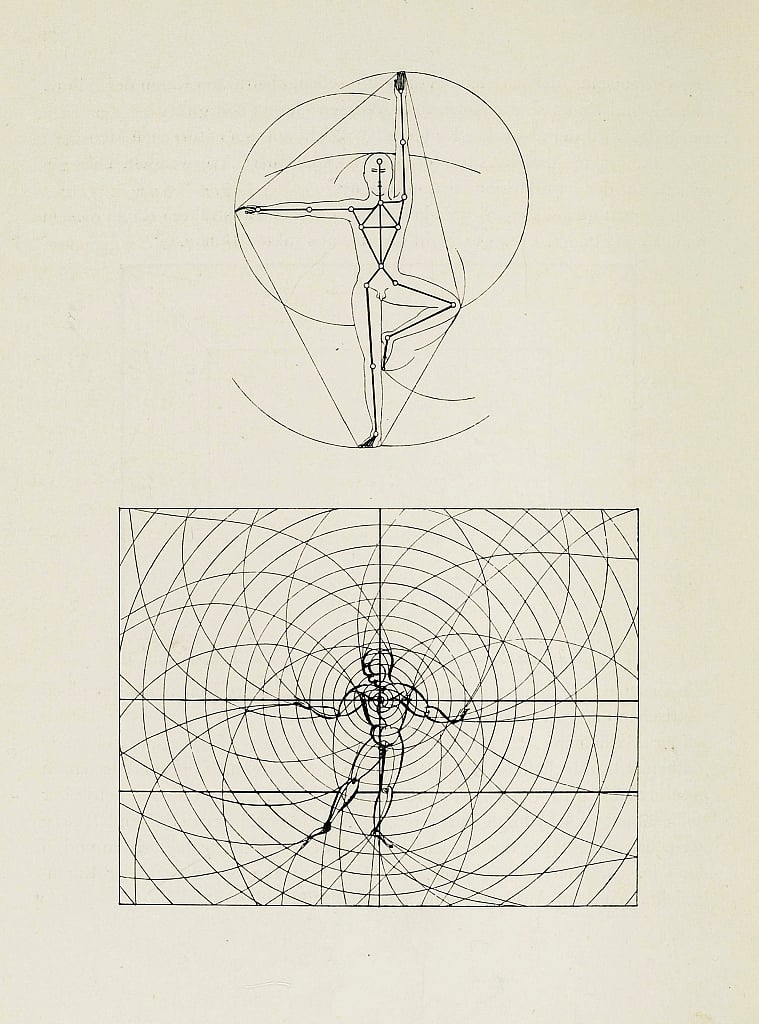

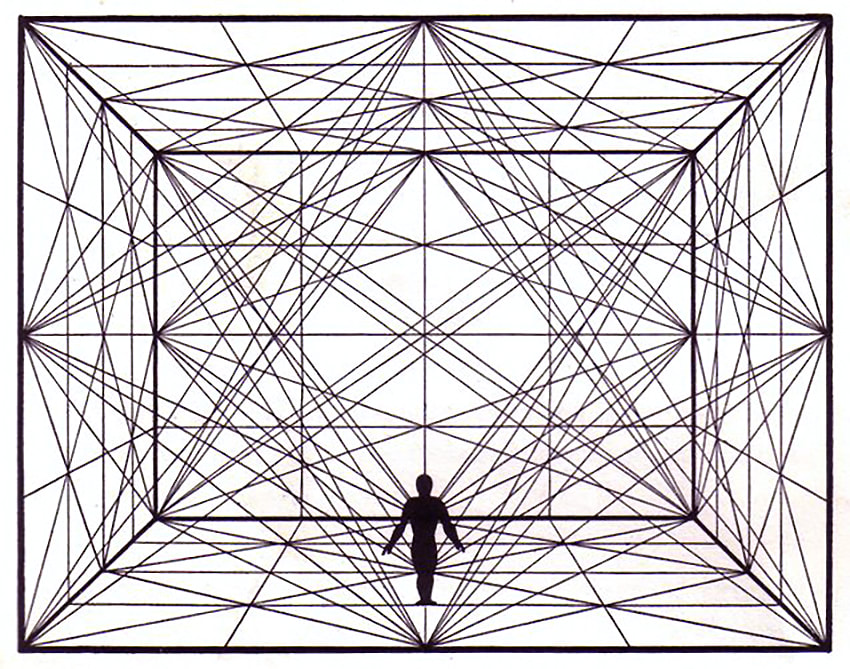

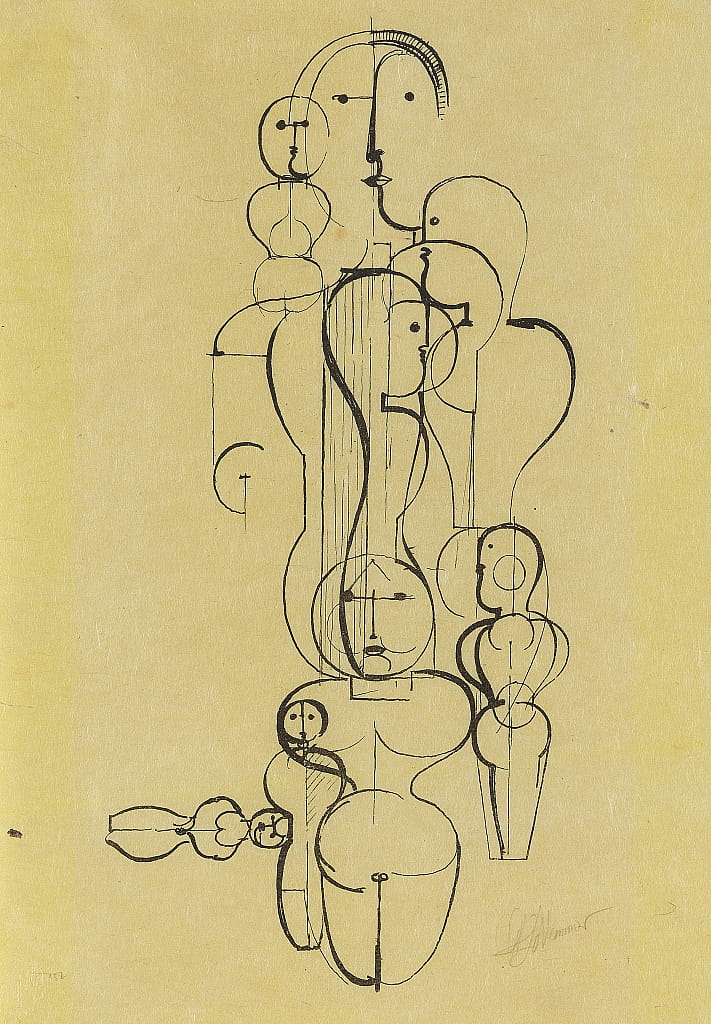

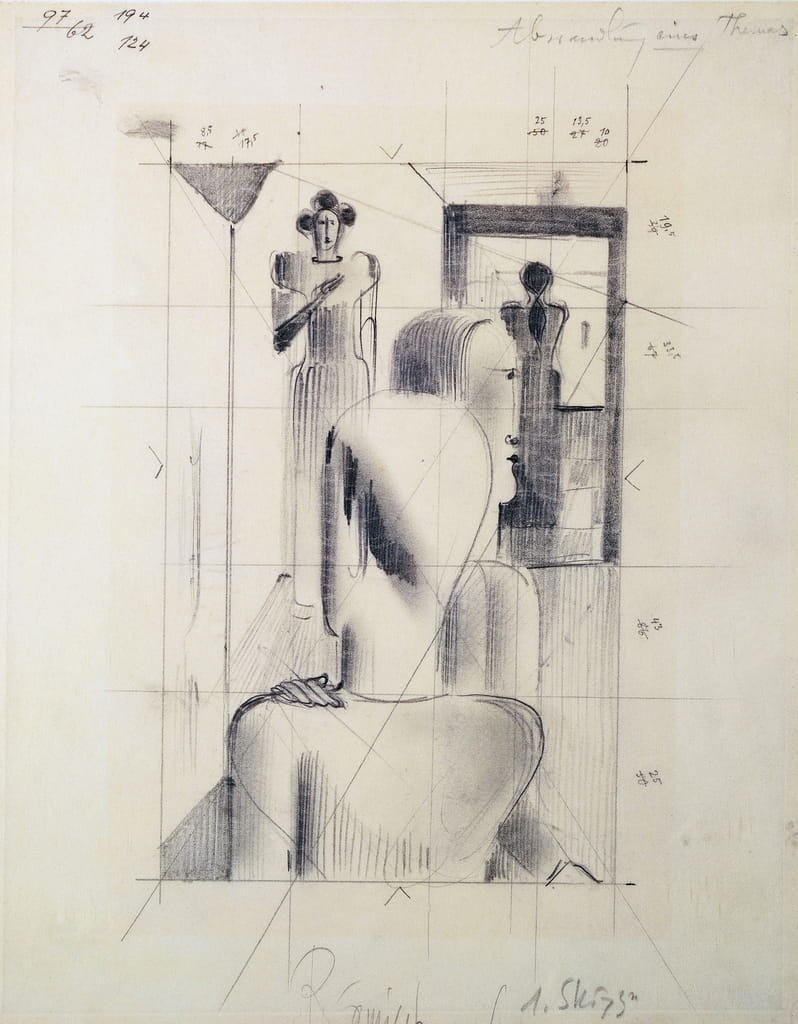

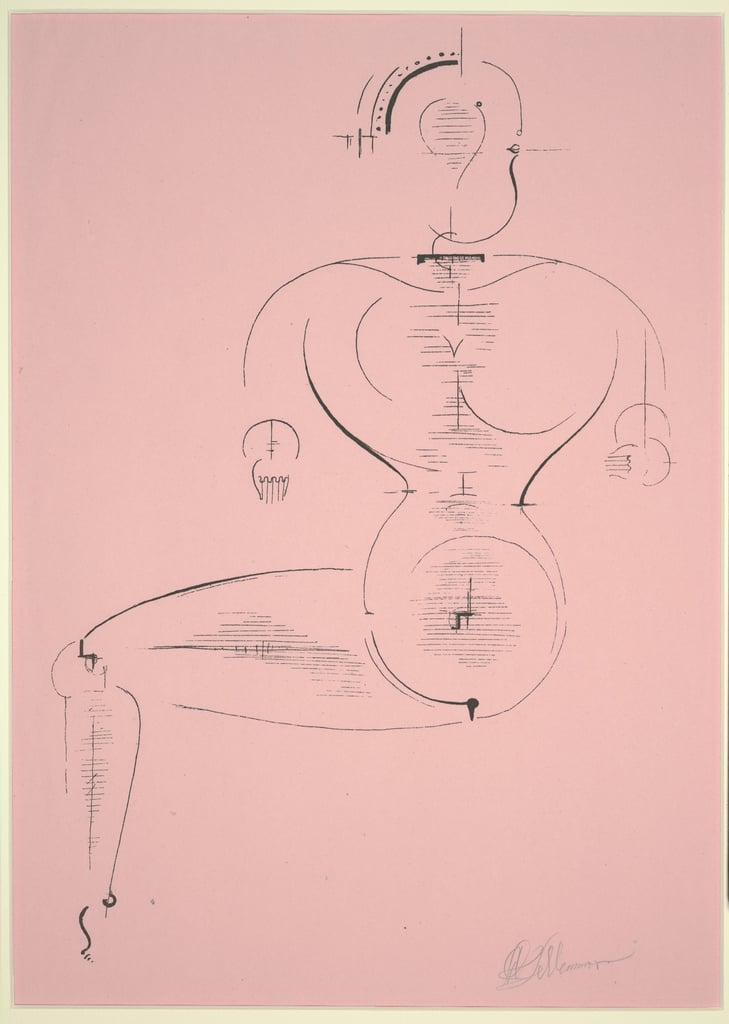

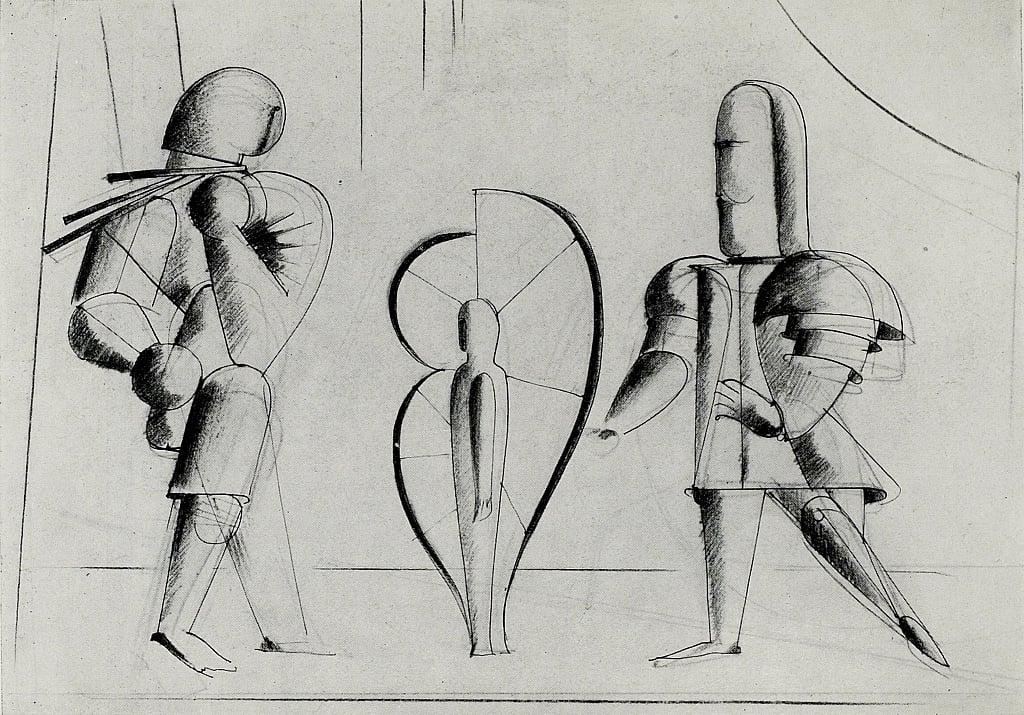

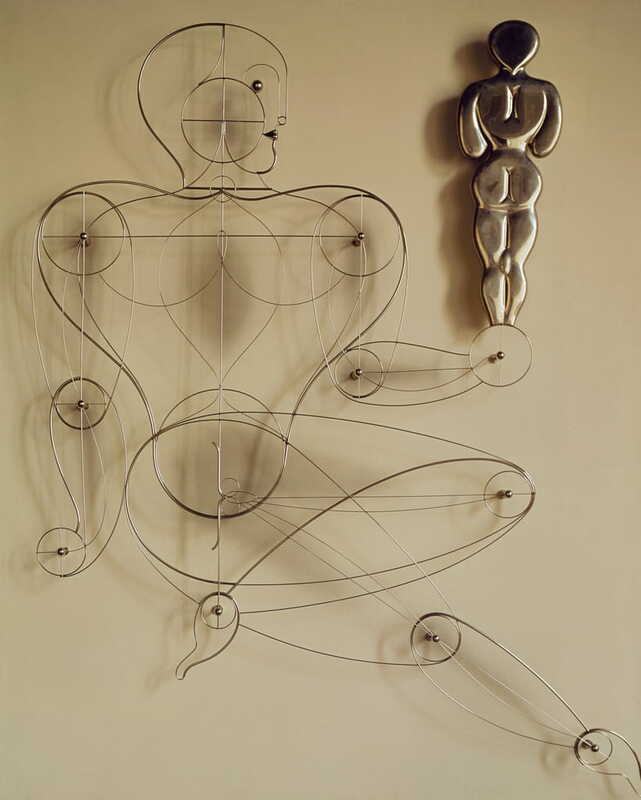

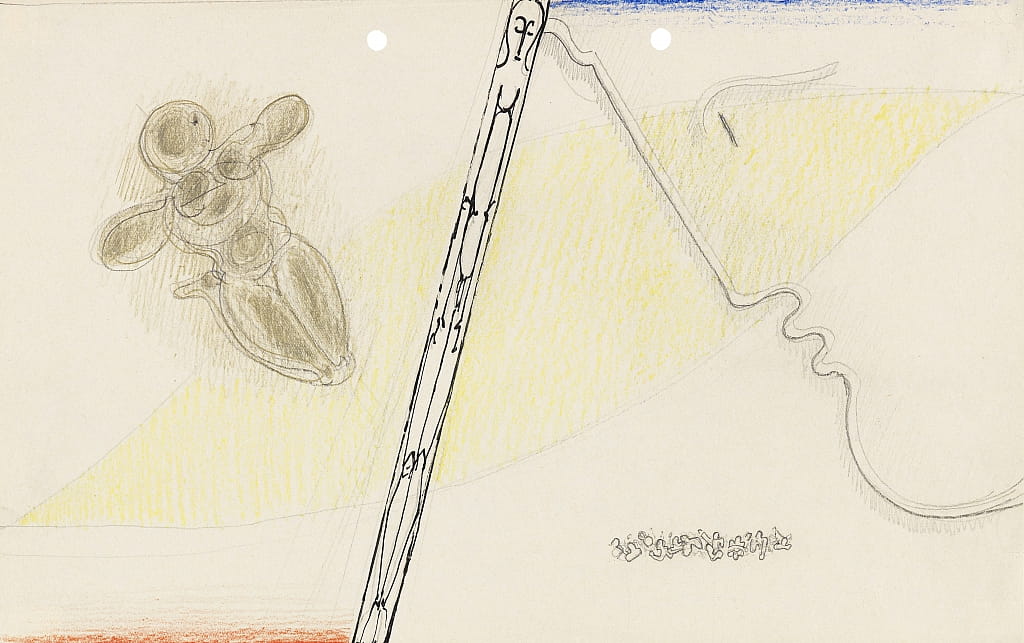

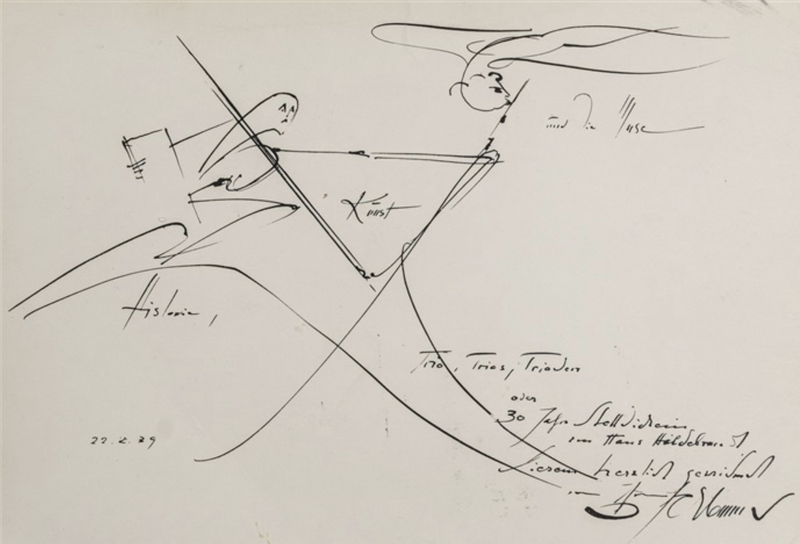

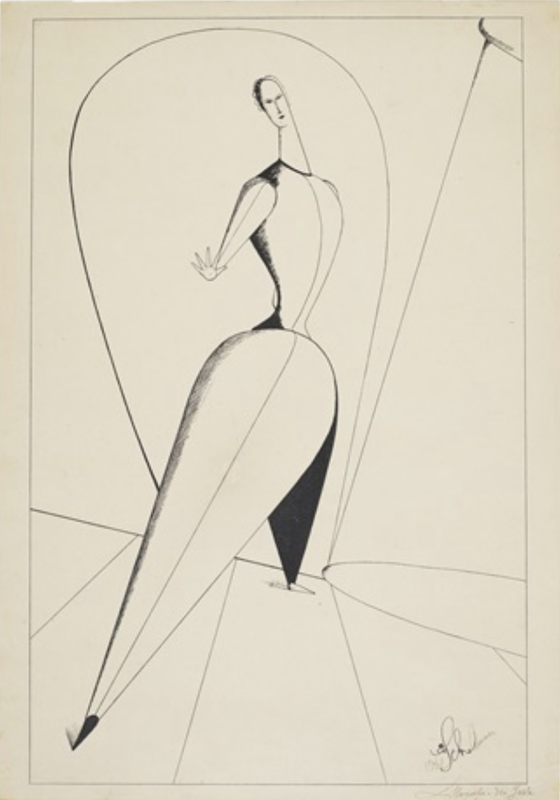

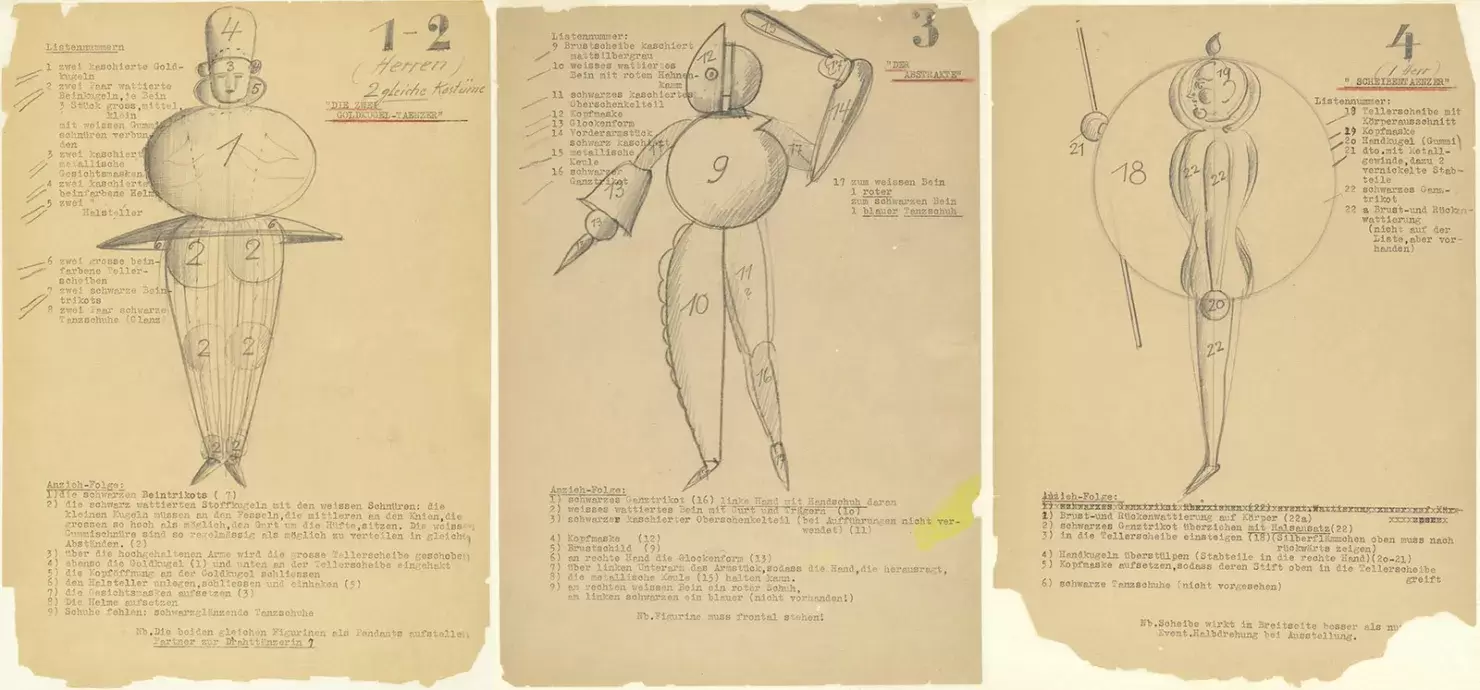

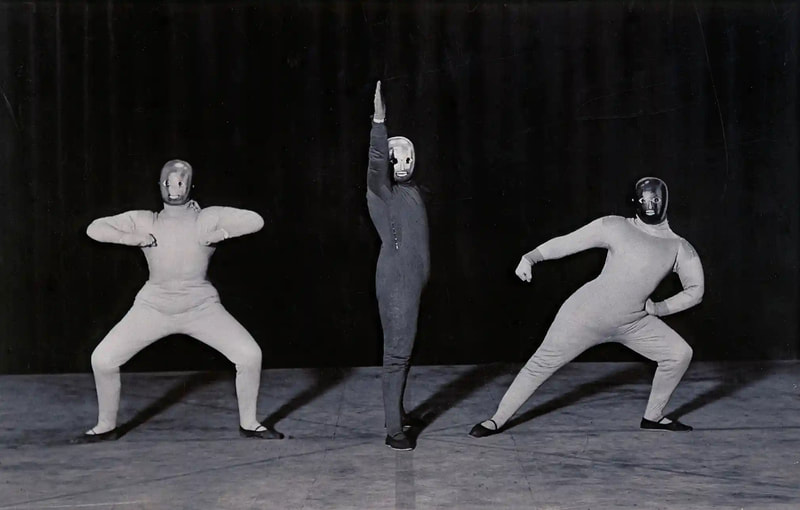

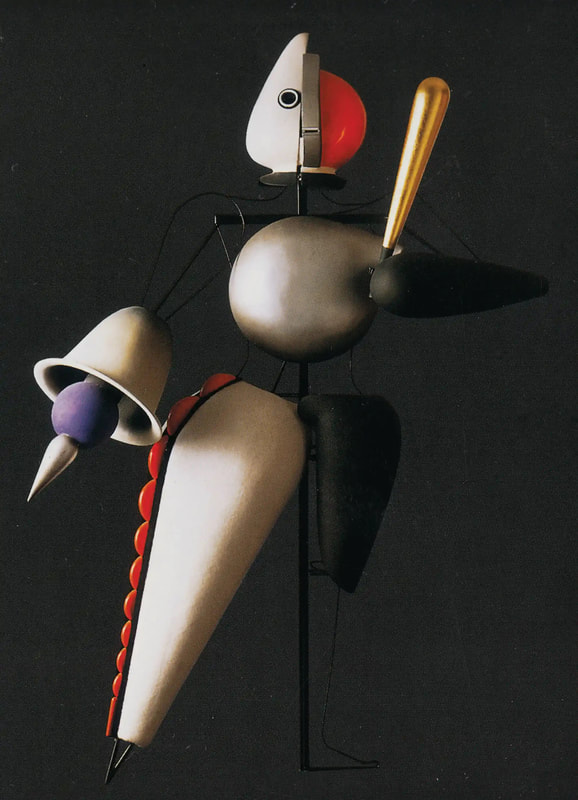

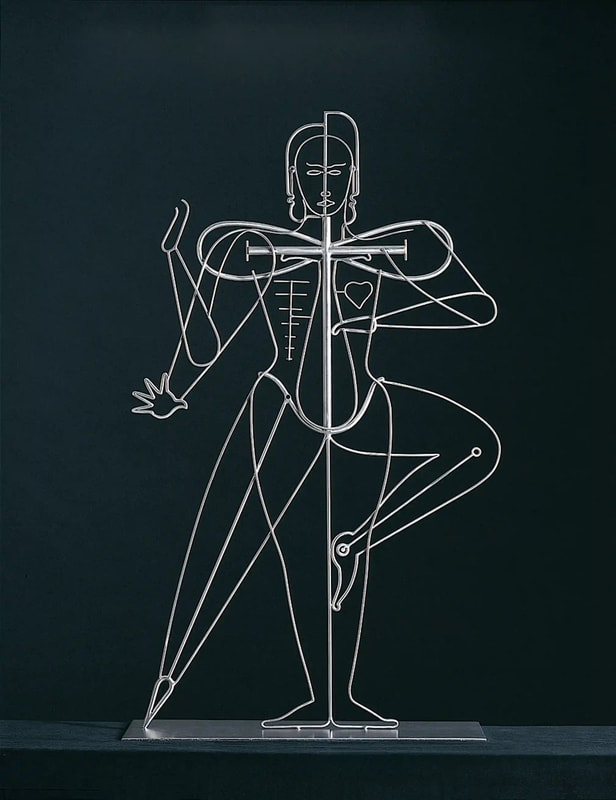

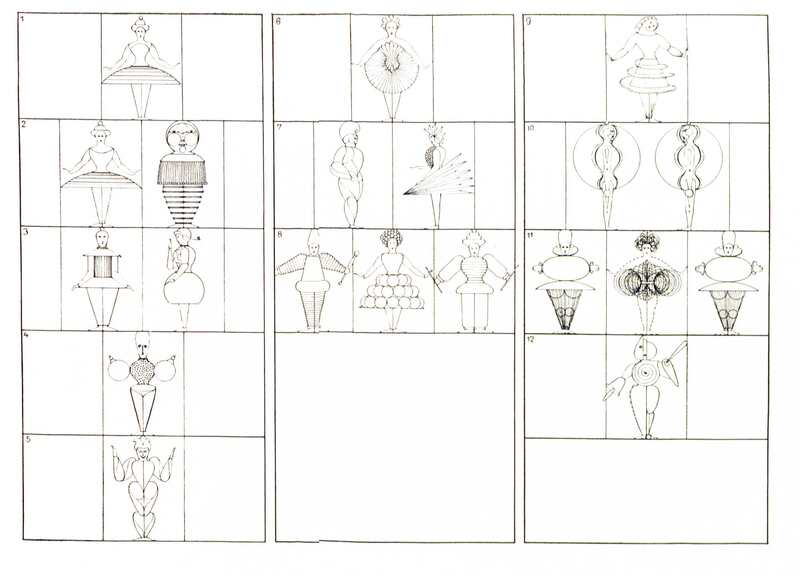

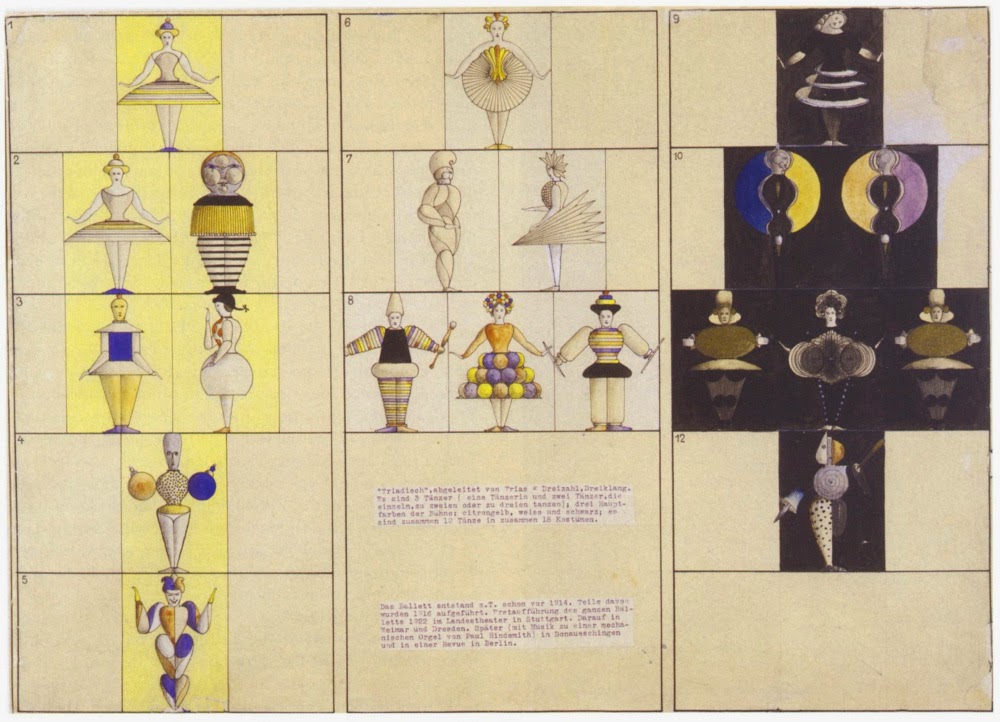

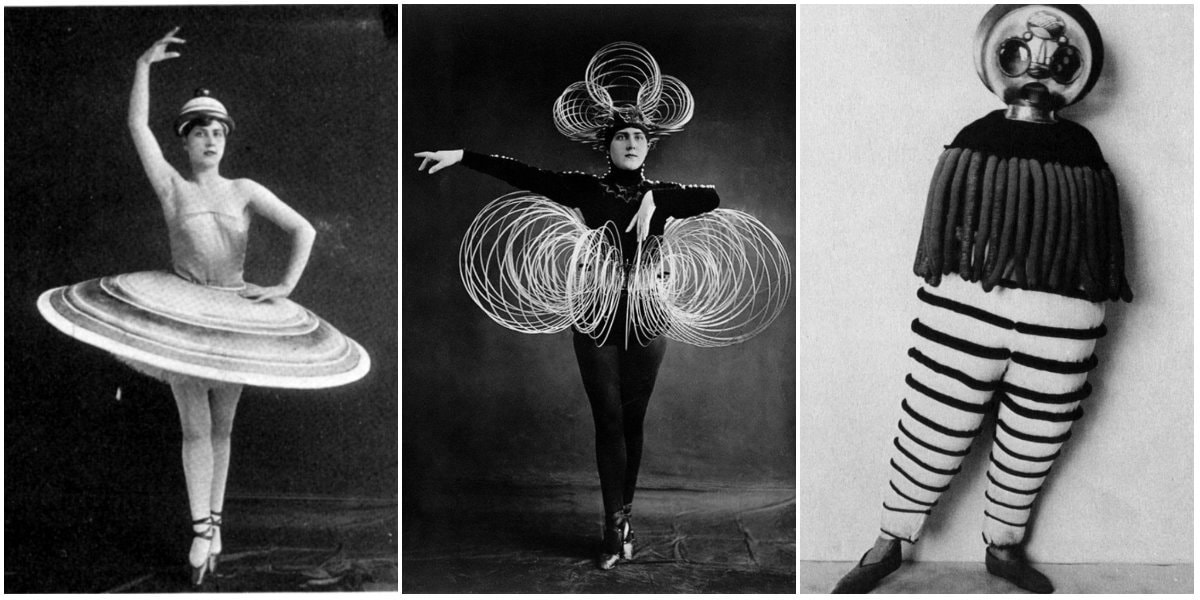

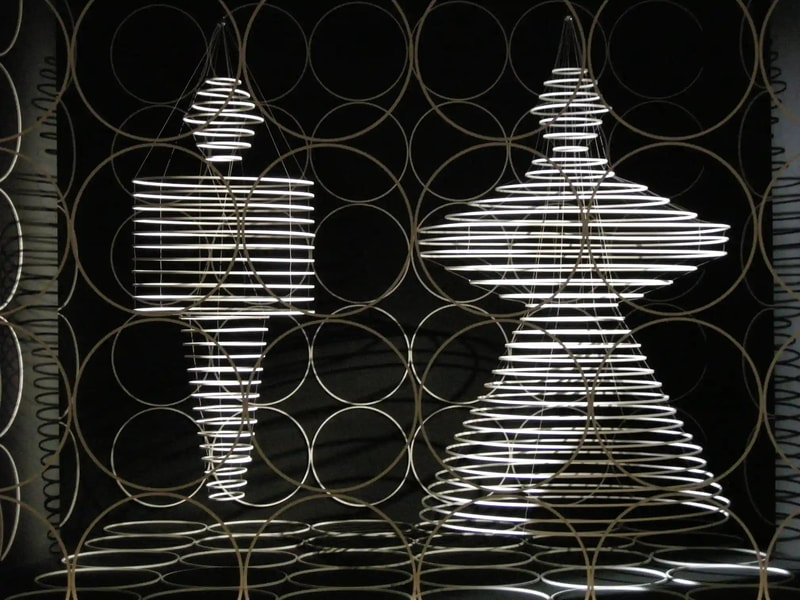

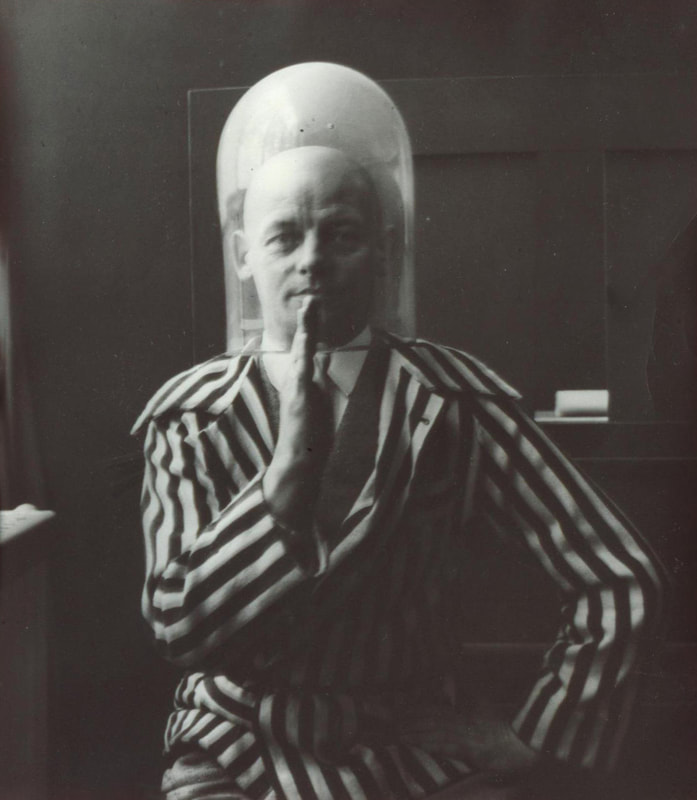

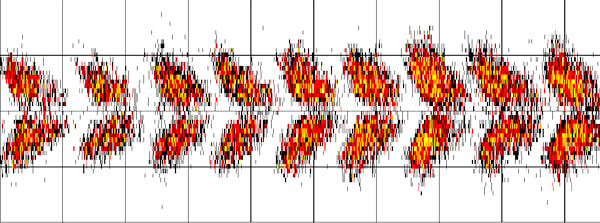

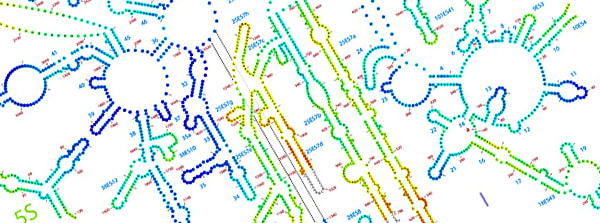

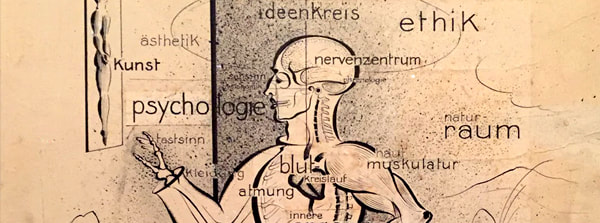

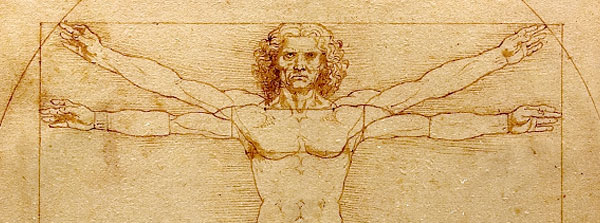

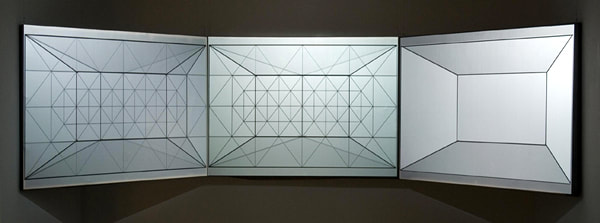

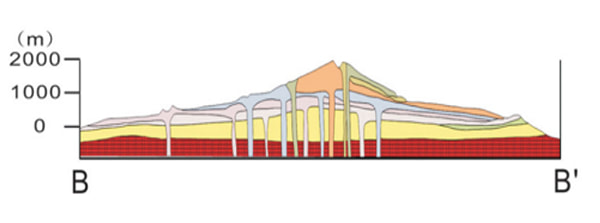

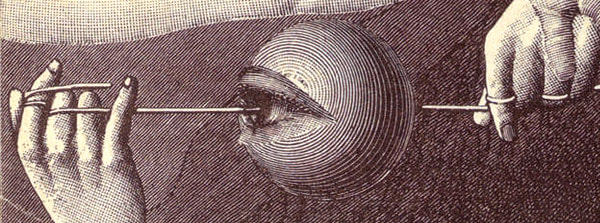

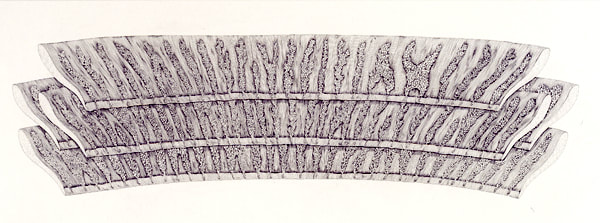

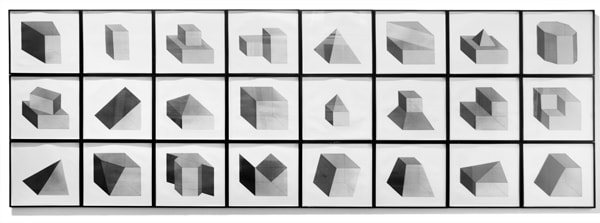

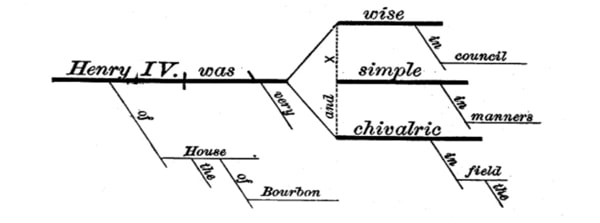

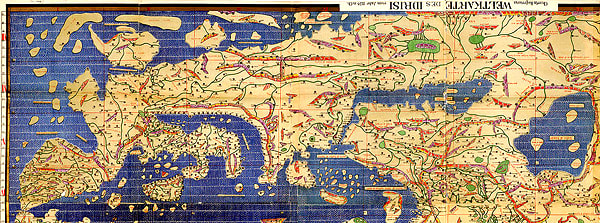

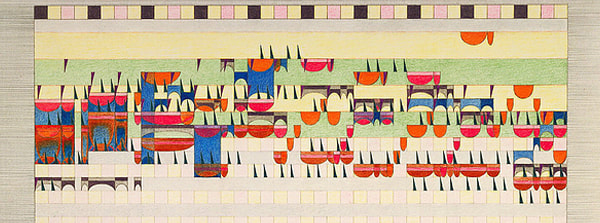

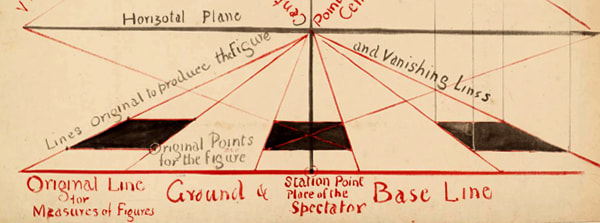

❉ Post 21 on diagrams in the arts and sciences explores the highly influential ideas and images of the German painter, sculptor, choreographer, and diagrammer, Oskar Schlemmer. As with Leonardo da Vinci, whose diagrams were discussed in the previous post, Schlemmer was captivated by the mechanics and geometry underlying life, and he contrived a range of experimental objects, images and performances based on human movement, gesture and thought in physical and metaphysical space. Figure 1: Oskar Schlemmer, Figure in Space Bauhaus Archiv, Oskar Schlemmer 'Der Mensch' original photograph by Lux Feininger. Photo: Marcia F. Feuerstein. In previous posts we've looked at the work of highly influential artists who've held a profound affinity for the art of diagram making. A significant number of these artists were self-taught or received training in diagram creation, a factor that played a pivotal role in shaping not only their personal artistic evolution, but also left a lasting impact on the broader history of art. Leonardo da Vinci, a polymath of the highest order, harnessed the power of diagrams to visualise complex natural systems, generate detailed technical solutions to engineering projects, and construct the complex systems of perspective that underly many of his masterful paintings. JMW Turner, England's most celebrated romantic period artist embarked on his career as an apprentice to an architect, honing his skills as a draftsman. He taught for over 30 years as Professor of Perspective at the Royal Academy, often adding this accolade when signing his paintings as PP. Marcel Duchamp's artistic evolution was profoundly influenced by his intensive study of French textbooks brimming with austere diagrams during his time in art school, helping to catalyse his shift away from what he called 'retinal art' designed only to please the eye. In a fascinating twist, this influence extended to his proteges Arakawa & Gins, with Arakawa's fascination running so deep that he contemplated changing his name to the word 'Diagram' itself. The master of diagrammatic conceptual art, Sol LeWitt, embarked on his artistic journey as a graphic designer in the esteemed office of world-renowned architect I.M. Pei. Like Duchamp, his obsession with the work of 19th-century diagrammatic photographer Eadweard Muybridge added yet another layer of complexity to his creative repertoire. Contemporary Swiss artist Yves Netzhammer's background in architecture, including training in architectural drafting, left a lasting imprint on his art, which is characterized by an engaging yet disconcerting mixture of diagrammatic images with contemporary neuroses. In the case of the legendary Bauhaus teacher Oskar Schlemmer, an early training in cartography significantly fueled his interest in combining formal, geometric clarity with subjective experience and dynamic expression. In Schlemmer's own words he felt as if he must , "...opt for Cezanne or Van Gogh, classicism or romanticism, Ingres or Delacroix, Leibel or Böcklin, Bach or Beethoven. I would like to present the most romantic idea in the most austere form." (1) The austere form he chose was the diagram. Figure 2: Oskar Schlemmer, Die Buhne im Bauhaus Gegenüber (The view in the Bauhaus opposite), 1925 In 1914, at the outbreak of war, a 22 year German old art student named Oskar Schlemmer left his position as master pupil of abstract artist Adolf Hölzel, and travelled to the Western Front. One of almost 4 million men mobilized to fight, Schlemmer served until he was wounded in April 1917, after which he was transferred to the military cartography unit in Colmar, France. World War 1 was primarily a war of maps, and these were produced in their tens of thousands by these teams of military specialists whose job it was to survey the terrain and keep maps up to date based on direct observation, sound ranging, and other specialised techniques. The recent invention of Airplanes allowed for daily aerial reconnaissance of enemy troop positions in their labyrinthine trenches. Working at 12,000ft above enemy positions, photographers would lean from their so called 'flying coffins' to photograph troop locations, often flying treacherously low to capture critical details. As a time saving measure, film canisters and observational notes were dropped directly over map makers' workshops, allowing for the quickest possible cartographic updates. Figure 3: Fourth Army Front: Aerial reconnaissance of Thiepval village, and German front-line and support trenches, 1916-06-01. Courtesy of Imperial War Museum © IWM HU 91108 Experimental aerial photography from balloons and rockets did exist prior to the outbreak of WWI, however Schlemmer's work in the cartography unit in Colmar was likely to have been his first encounter with these unusual photograph that portray organic and geometric patterns from an objective, detached, gods-eye-view. The process of deciphering the photographs to create new maps must have aligned with Schlemmer's own artistic interests in formal clarity, and his shift from expressionism towards abstractionism and cubism. As Schlemmer later commented, "I have always admired the fantastic aspect of a drawn map. Purity in respect of art is thus nicely preserved for me." (2) In 1918, after returning to civilian life, he resumed his artistic studies under the guidance of Hölzel, but began to venture beyond traditional painting into the realm of 3-dimenions, crafting a series of sculptures that garnered attention when exhibited at the renowned 'Der Sturm' Gallery in Berlin. Simultaneously, Schlemmer found himself working alongside the esteemed artists Paul Klee and Willi Baumeister at the Stuttgart Academy of Fine Art. However, the most transformative chapter in Schlemmer's career came when he received an invitation to teach at the Weimar Bauhaus from Walter Gropius, who had founded the school in 1919 in the wake of World War I. Figure 4: The Masters of the Bauhaus, c.1928. Google Arts and Culture, © Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau Primarily recognized as a painter, Schlemmer's initial teaching role at the Bauhaus focused on wall painting and sculpture. Yet, his influence extended far beyond these traditional boundaries. In 1922, Schlemmer showcased his creativity when he completed the design and choreography for a performance he had started working on over a decade earlier. His iconic 'Triadic Ballet' would leave an indelible mark on the world of theater and art, and is still celebrated and performed today, and by 1923 Schlemmer had ascended to the position of Master of the Theatre Workshop. When the Bauhaus moved to Dessau in 1925, Schlemmer developed a series of architectural courses that incorporated his knowledge of theatre, choreography and the human form, underpinned by his interest and experience in diagrammatic image making. This innovative fusion of disciplines set a precedent for the interdisciplinary approach that would come to define his educational philosophy. However, Schlemmer's most groundbreaking venture came in 1928, when he introduced an obligatory course for third-year students, titled 'Der Mensch,' or 'The Human Being.' This visionary program cast humans as dynamic agents composed of intricate anatomical and hereditary systems, active participants within vast networks that encompassed not only their physical environments, but higher spheres of metaphysical concepts and ideals. This transdisciplinary approach foreshadowed the development of fields like cybernetics and systems science, which would emerge only later in the 1940s. To convey the essence of his new course, Schlemmer composed and refined a diagram titled 'Man in the Sphere of Ideas' featuring a semi-transparent figure frozen in motion (figure 2). Figure 6: Der Mensch im Ideenkreis (Man in the Sphere of ideas), Oskar Schlemmer Figure 7: Der Mensch im Ideenkreis II (Man in the Sphere of ideas II), Oskar Schlemmer Figure 8: Der Mensch im Ideenkreis II (Man in the Sphere of ideas II), Oskar Schlemmer English translation by Michael Whittle. In a stylised reference to the Vitruvian Man, Schlemmer's figure floats in a bubble of words, grounded by the earth and centered on vertical and horizontal axes. Like the flesh of the body, the walls of the building are transparent, so that beyond the architecture we can see the nature, space and vegetation it's constructed within. In the sphere of ideas surrounding the head hover the higher abstract concepts of psychology, aesthetics and ethics, whilst overhead fly more esoteric ideas such as astrology, and in an early draft the classical element aether, or the void. According to Marcia Feuerstein, Schlemmer was astounded by his students’ lack of even a basic knowledge of the human body, and began by having them make figure drawing of one another. (3) For the series of lectures that became the basis for his new course, Schlemmer referenced Adalbert Goeringer's book 'Der Goldene Schnitt', or Golden Circle, which emphasised the fundamental importance on the golden section in the study of proportion. Schlemmer also referred to other historic canons of human proportion including the ancient Canon of Polyclitus, the Egyptian canon, Albrecht Dürer’s various studies, and Leonardo da Vinci’s reinterpretation of Vitruvius’ proportional body (Figure 1) (See also a previous blog post on the Vitruvian Man). Figure 9: Pages 58-59 of Schlemmer's textbook 'Der Mensch' for the Bauhaus In his theatre productions Schlemmer continued to further refine and codify the body as an iconic representation, which stood him in contrast to the psychological and emotionally expressive approaches common to German dance of the 1920s. Indeed, Schlemmer was already aware of the pioneering work of the physiologist J.E. Marey, who laid the groundwork for a quantitative study of human motion that led to the scientific classification of key parameters in this rapidly developing field. Figure 10: Jules Etienne Marey, partial chronophotography and motion capture costume, c. 1880 Marey designed sensors and devices to record the motion of humans and other living organisms. In the 1870s, he developed a graphic method that translated these movements into lines, curves, or graphs within a Cartesian coordinate system. However during the 1880s, he integrated photography into his motion analysis techniques, which ultimately led to his renowned contribution to 'partial chronophotography'. This transition from describing the so called 'sensual body' using words and drawings, to generating more accurate scientific data had a significant impact on the performing arts, particularly in the realm of dance and choreographers such as Schlemmer. (4) For his performance known as 'Stäbetanz' or 'Slat Dance', Schlemmer used white wooden sticks to extend the limbs of a dancer. This highlighted the geometric relationship between the human body and space, and Schlemmer mirrored the methods of Marey by obscuring the body itself by using a black costume against a black background. Figure 11: Stäbetanz (Slat Dance') by Oskar Schlemmer, 1927. Choreographer and scholar Debra McCall reconstructed the Bauhaus Dances using Schlemmer’s original notes and toured them internationally in the 1980s. In an interview McCall spoke of how her teacher “...Martha Graham said that where the dancer stands ready is hallowed ground. She understood the sacred aspect of theatre, and Schlemmer felt very much the same. He believed that walking, standing, and sitting are very serious, and that [just] to see a figure on a stage is serious as well. The Stick Dance, for example, is the extension of the golden mean into space because our anatomical form is based on those proportions; it is sacred geometry in motion. When you see it and the other pieces performed, it’s like being in church. You will not hear a sound in the theatre.” (5) Figure 12: Scene from Stäbetanz (Slat Dance') by Oskar Schlemmer, 1927. Schlemmer's also experimented with choreographic diagrams for his 1926-27 performance "Gesture Dance". These images graphically mapped out the entire sequence of actions, although he recognized that even with directions for tempo and sound, notation still couldn't provide a complete depiction of the performance and supplemented them with written descriptions. (6) Below are images and a recording of the Triadic Ballet, as well as a series of other diagrammatic forms created by Schlemmer in his visual and conceptual quest to codify and simplify the complexity of life and living. He used music as an analogy to describe his preference, stating that ''...what I love most are plain, austere things. Not flowery, scented, silky, Wagnerian things but Bach and Handel.'' (7) Figure 13: Oskar Schlemmer, Diagram for Gesture Dance, 1927-27. Oskar Schlemmer, Figur und Raumlineatur, (figure and spatial delineations), 1926 References:

1) Schlemmer, Oskar, pg 28. The letters and Diaries of Oskar Schlemmer (1958), ed. Tut Schlemmer, trans. K. Winston, (Evanston, IL. Northwestern University Press, 1990) 2) Conzen, Ina, Oskar Schlemmer: Visions of a New World, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart (Hirmer Verlag, 2016) 3) Marcia F. Feuerstein (2019) Oskar Schlemmer's Vordruck: an absent woman within a Bauhaus canon of the body, Theatre and Performance Design, 5:1-2, 125-140, DOI: 10.1080/23322551.2019.1605767 4) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/221571982_Man_in_espacemov_Motion_Analysis_in_3D_Space 5) https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/2019/05/in-space-movement-and-the-technological-body-bauhaus-performance-finds-new-context-in-contemporary-technology/ 6) https://www.artforum.com/print/197707/oskar-schlemmer-s-performance-art-35972 7) https://www.nytimes.com/1986/05/25/arts/art-view-schlemmer-s-noncommittal-muse-came-to-life-on-stage.html?smid=url-share

0 Comments

|

Dr. Michael WhittleBritish artist and Posts:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|