|

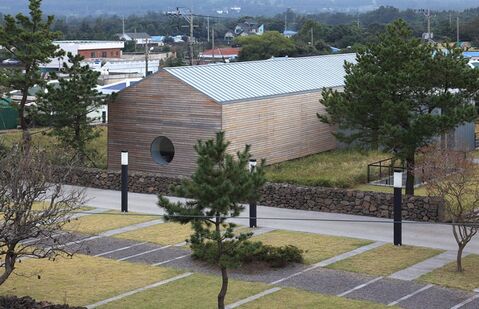

❉ Blog number 17 on diagrams in art and culture covers some of the ideas, images and research projects I discovered during a spring-time residency on the island of Jeju in South Korea. The two new drawings I developed following my stay there were on show in a group exhibition at the Chusa Memorial Museum from Oct 15th - Nov 17th, 2019.

figure 1: NASA image of Jeju Island

( United States Geological Survey Landsat data, Robert Simmon, Google Earth, 2000 )

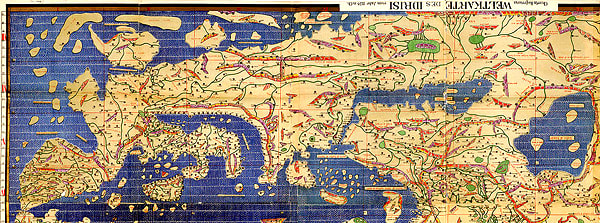

In the spring of 2019, I travelled to Jeju island, an eye-shaped volcanic landmass staring upwards off the southern coast of the Korean peninsula. I'd been invited by the Korean artist Mikyung Oh and her husband, the sculptor Do il, to take part in a group residency in connection with the Chusa Memorial Museum, during which time the selected artists were asked to respond to the works of the legendary Korean scholar and calligrapher after whom the museum is named (fig. 2).

Mikyung and Do il's main studios are in Yongin city just south of Seoul, but they travel regularly with their daughter Yule to Mikyung's hometown on Jeju to maintain the family tangerine orchard. The residency program is run from Mikyung's family home there, alongside a barn converted by Do il in to studio space. Once all the artists had arrived at the orchard we were welcomed by a Kayagum concert held beneath the heavy bows of one of Jeju's ancient Hackberry trees. Afterwards, we set about exploring the island and learning more about it's most famous historical resident Chusa Kim Jeong-hui, exiled scholar and man with two hundred names.

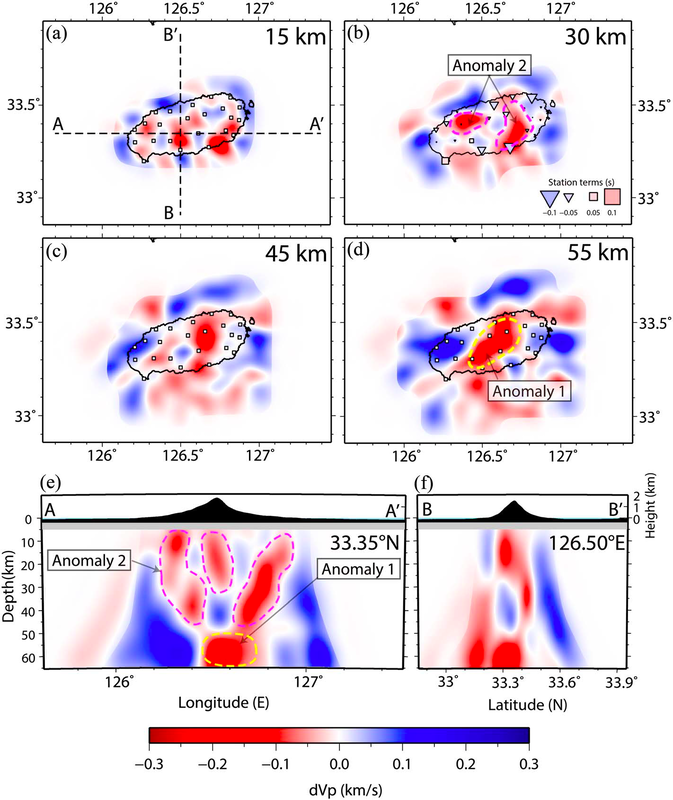

figure 3: Chusa Kim Jeong-hui’s masterpiece Sehando (A Winter scene),

1844, National Treasure #180 ( public domain )

Geology and the molten roots of an island

|

|

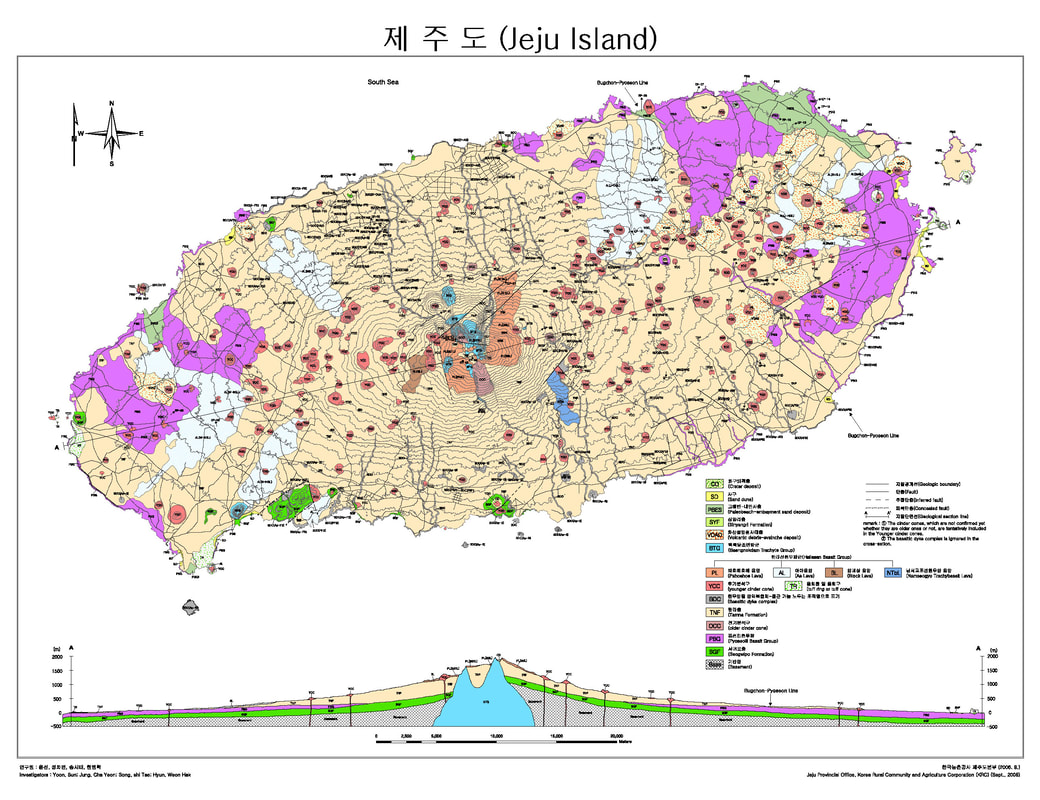

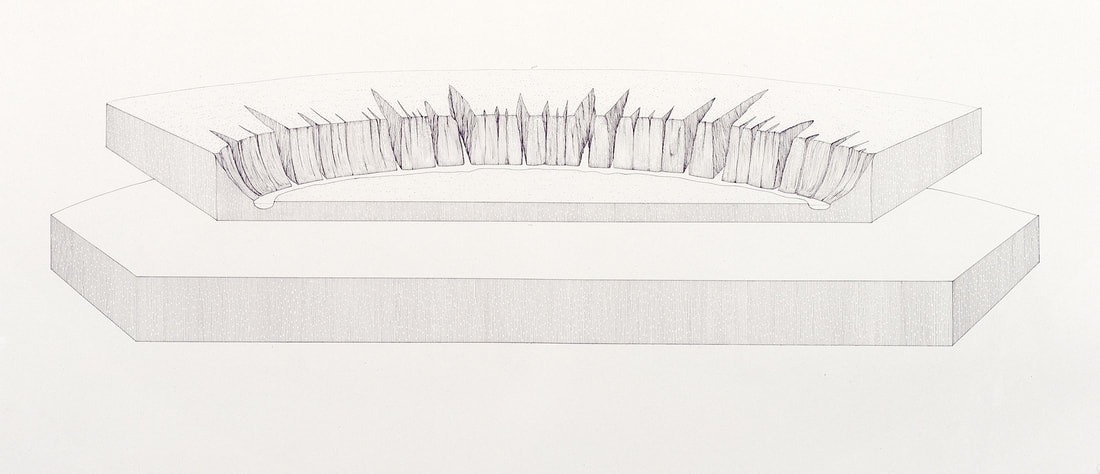

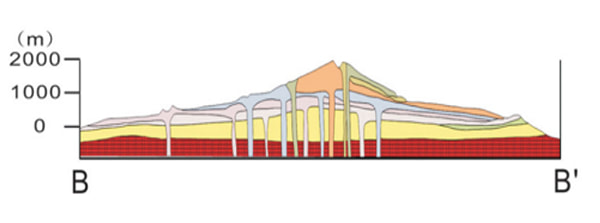

figure 6: Diagrams of Lithospheric Structures Beneath Jeju Island

Image courtesy of Jung-Hun Song (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) |

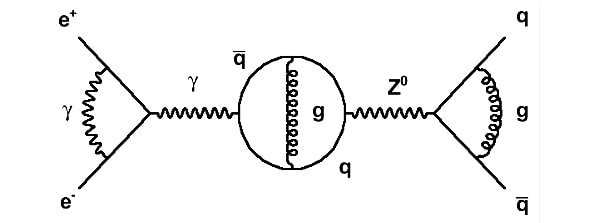

Between 2013 and 2015, a team of Geologists from Seoul and Busan used 20 seismographic stations across the island to record waves passing through the earth from the 484 different earthquakes that had occurred in neighboring regions during that period.

Earthquake waves are known to travel at different speeds through different types of rock. By carefully comparing the arrival times of the waves at each station against which routes they had taken through the earth, (a process known as 'Teleseismic Traveltime Tomography'), the scientists were able to model the enormous bodies of magma beneath Jeju, giving us our first look at the vast molten roots of the island and a clearer understanding of how these systems develop (fig. 6). |

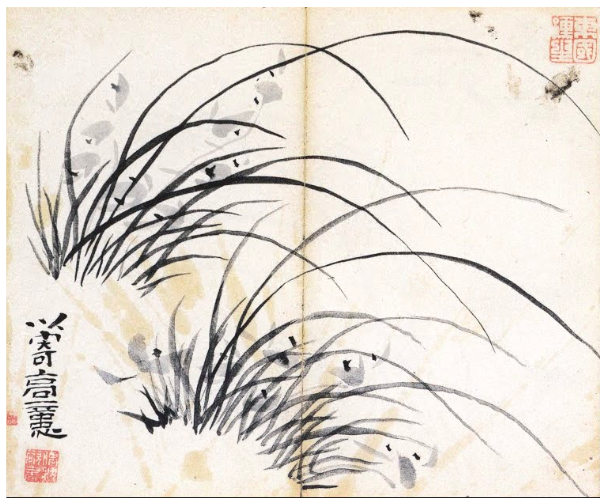

Biology and the genetic roots the orchid

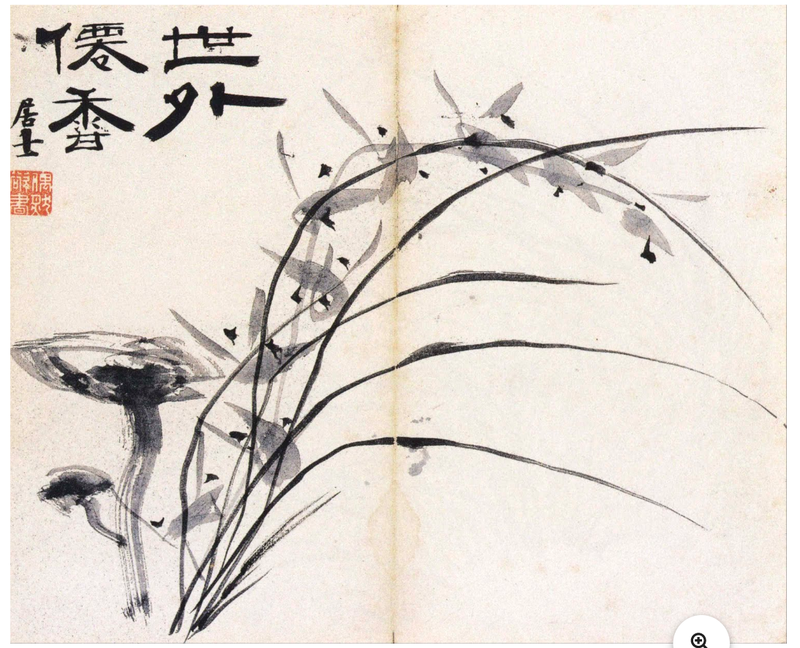

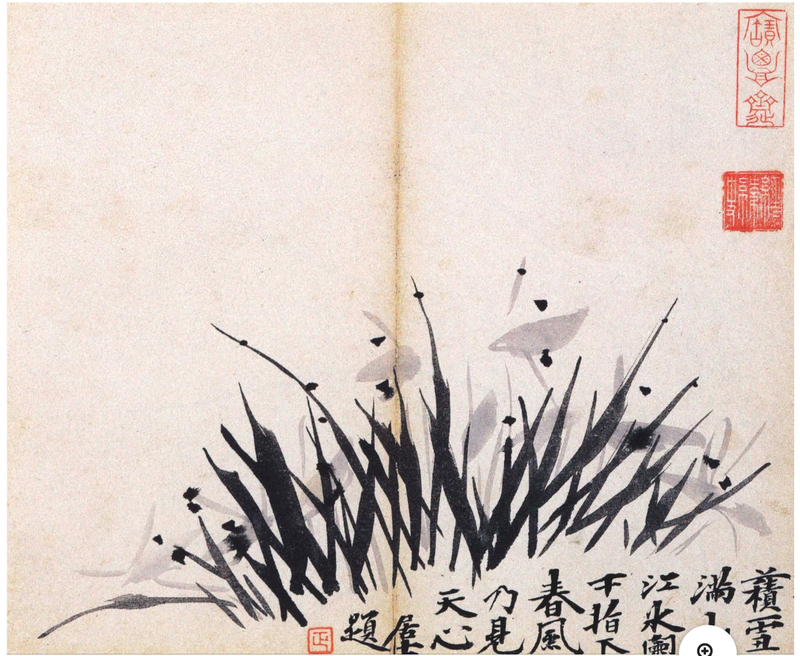

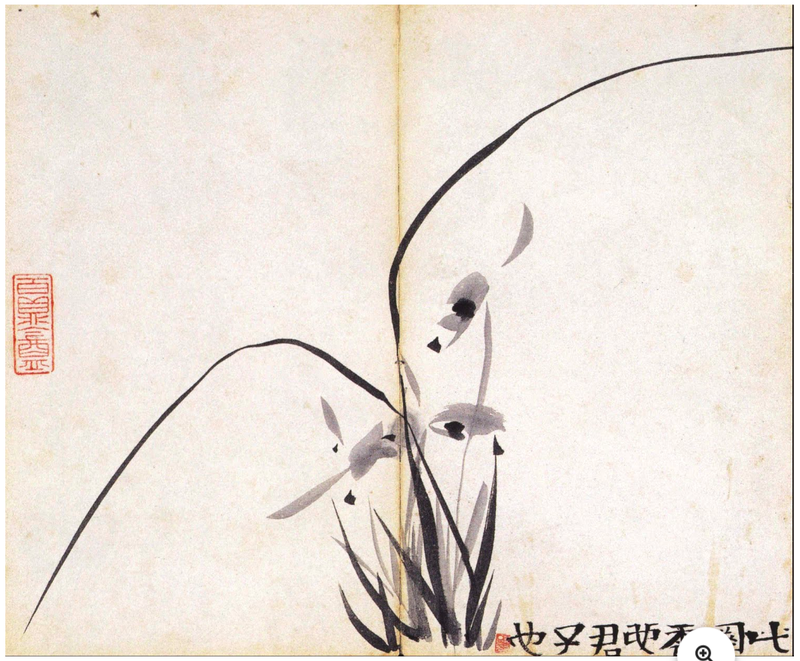

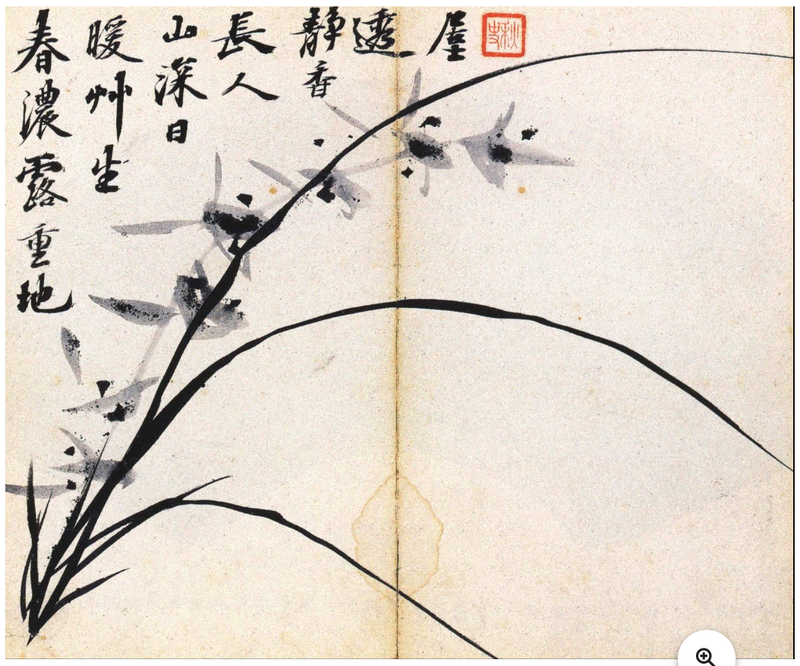

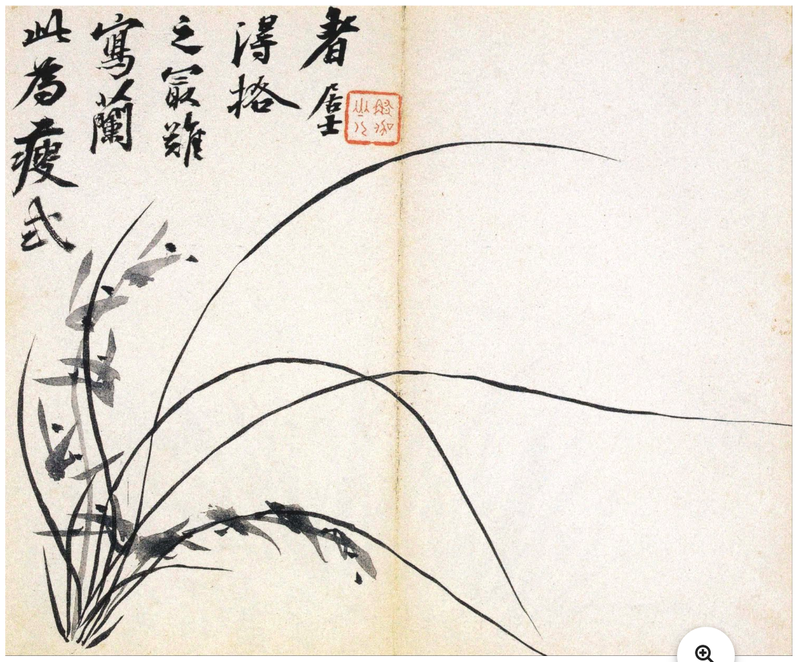

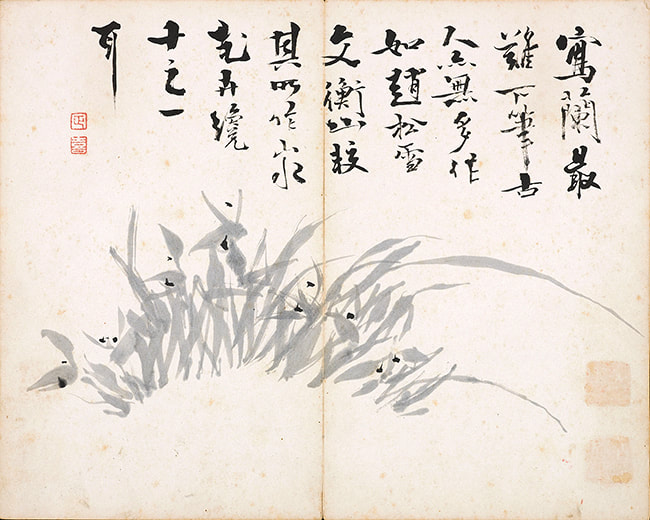

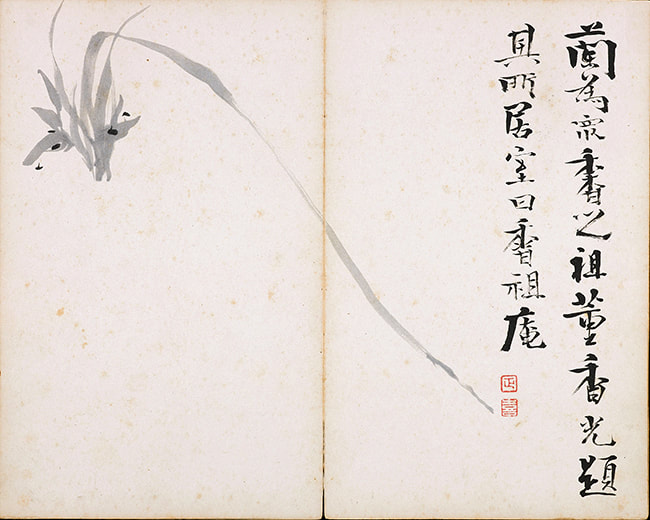

Chusa's brush of choice was made of rat’s whiskers, a material which he found combined strength with sensitivity, and also allowed him to abruptly change the direction of his stroke whilst painting. With each new painting he would often coin a new 'Ho' or pen-name when signing the piece, to suggest a particular persona in association with the image.

|

figure 8: Orchid painting, Chusa

(unknown date, public domain) |

Over his life time Chusa created over 200 different pen-names for his calligraphy, poems and paintings, and according to his own accounts, in his 70 years he wore down 10 ink stones and 1,000 brushes whilst developing the distinctive Chusa style or 'Chusache'.

His most famous orchid masterpiece is said to have been made after not having painted a single orchid for 20 years, created in an absent minded moment as a gift for his young servant (figure 8). It's unlikely that his servant appreciated what he'd been given, but a local artisan certainly knew it's worth and continued to beg and pester Chusa for the scroll until it suddenly one day disappeared. Later, Chusa wryly added this tale to the painting itself in his unique 'Chusache' script (fig. 8). |

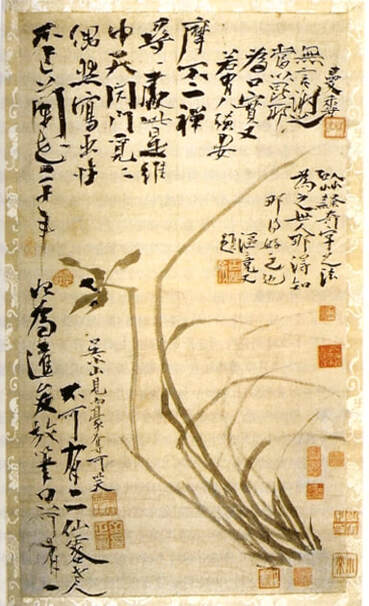

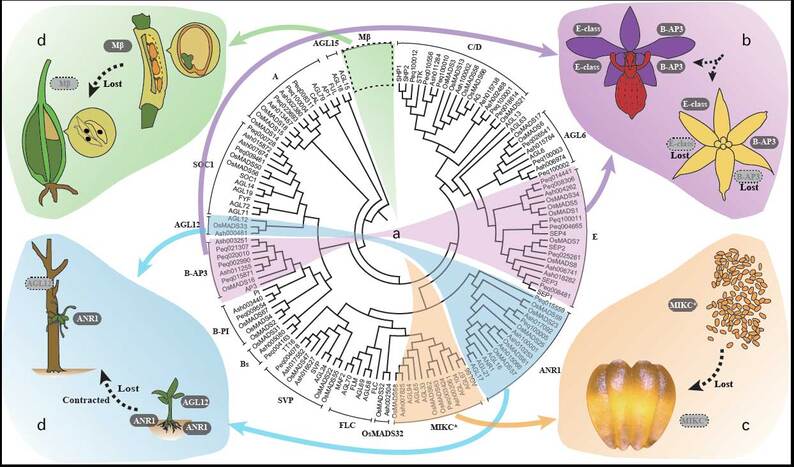

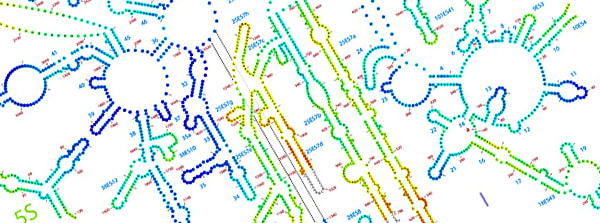

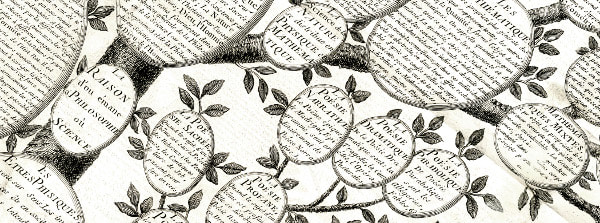

Around 10% of all flowering plants species are now known to be orchids, with somewhere between 20,000 and 30,000 species and over 70,000 hybrids and cultivars. Scientists are currently in the process of mapping out the extensive evolutionary lineage of orchids and in 2017, a study published in Nature Magazine announced that an international consortium of researchers had sequenced the genome of Apostasia shenzhenica, a primitive 'Grass Orchid' whose appearance is only barely recognisable as an orchid.

By comparing it's genome with known sequences in other species, they were able to estimate the time at which it diverged or 'split off' from other orchids. Their study also gives us a better idea of when the 'Most Recent Common Ancestor' (MRCA) of all orchids existed, now believed to be around 200 million years ago at the dawn of the age of the dinosaurs (figure 9).

figure 9: Phylogenetic tree diagram of MADS-box genes involved in orchid morphological evolution.

Image courtesy of Jie-Yu Wang and Rolf Lohaus (CC BY 4.0)

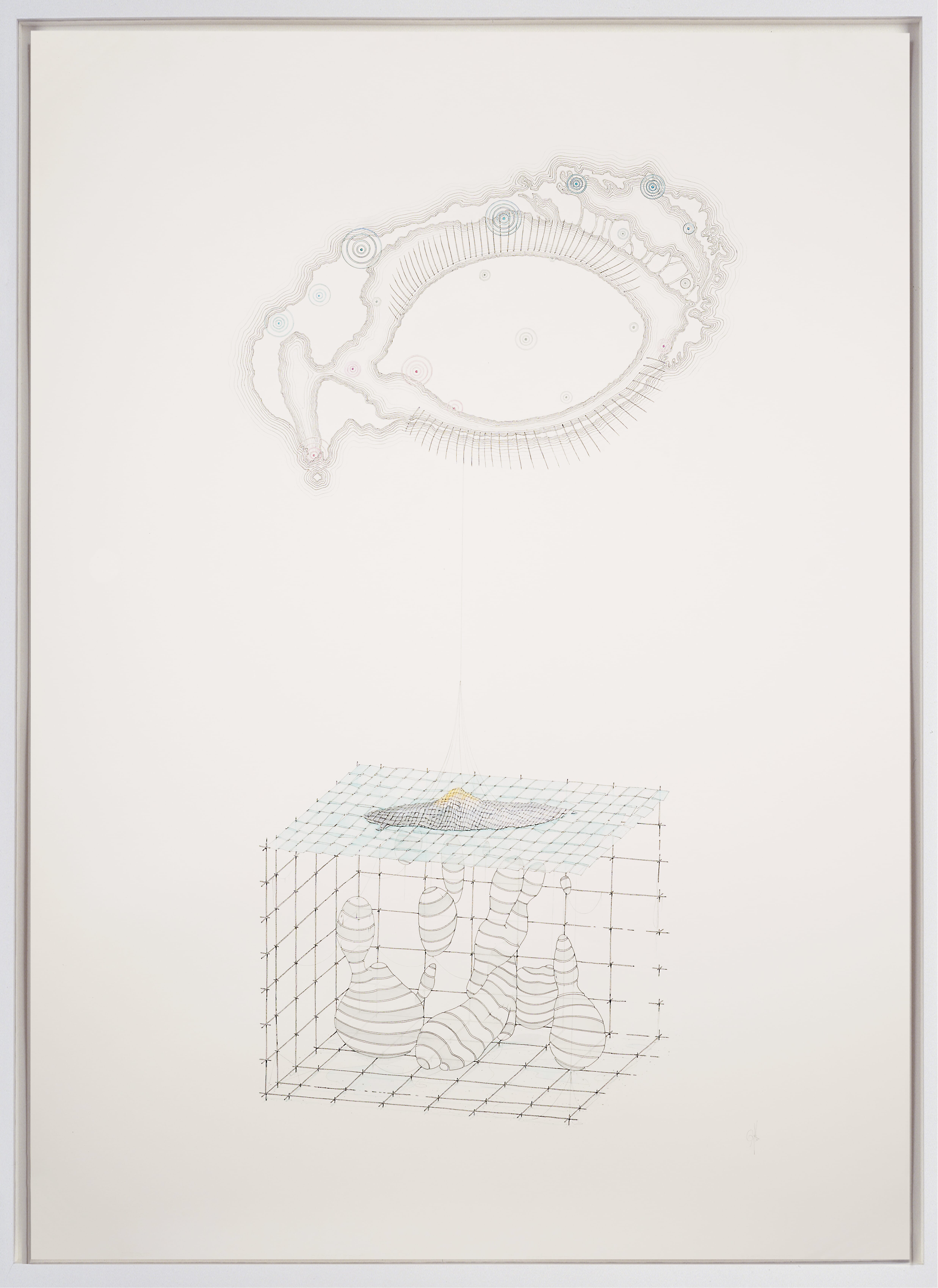

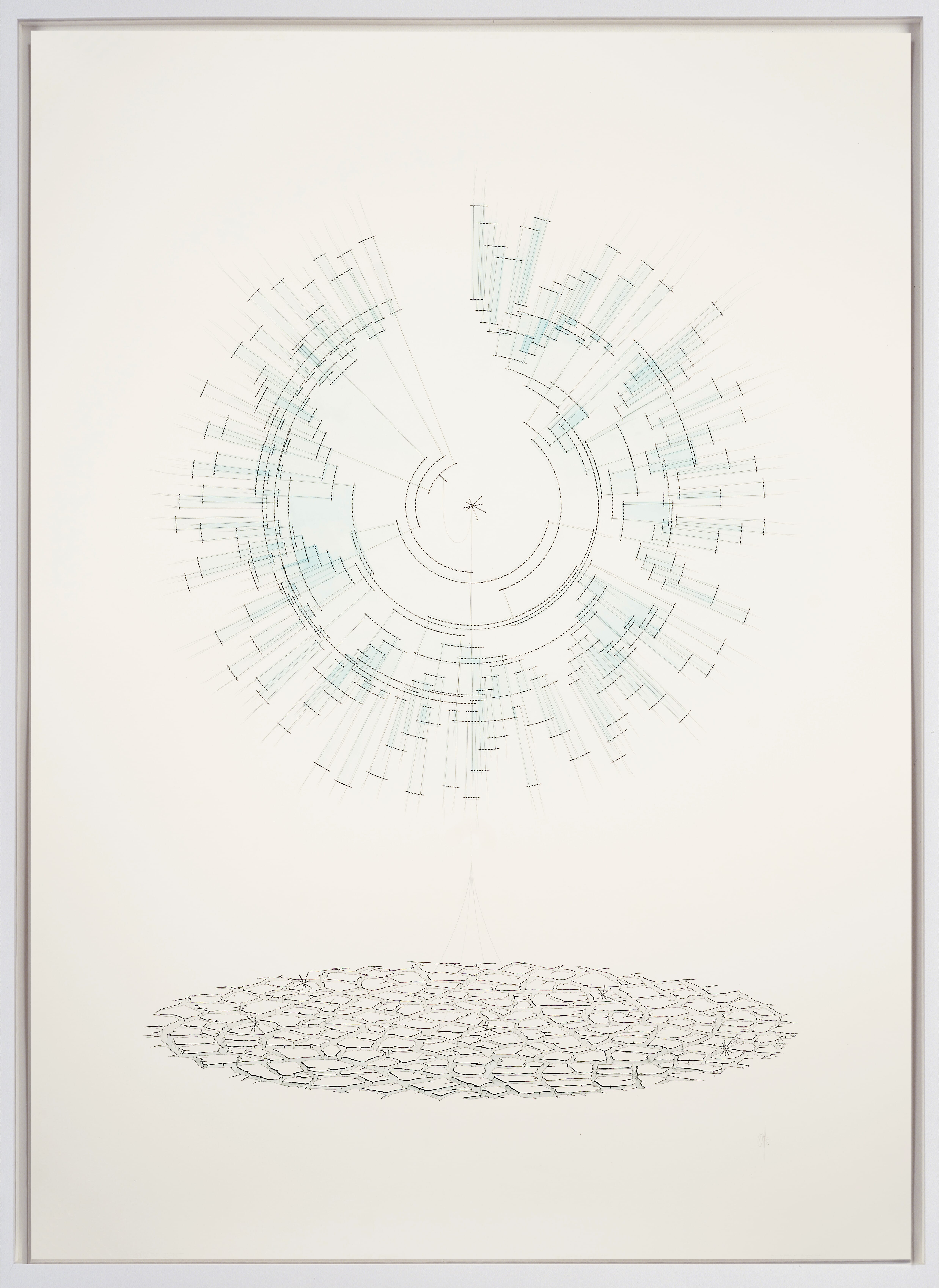

In developing the two new drawings for the residency on Jeju, I was interested in the notion of absence within an image - what an artist chooses to show and chooses not to, but also in terms of what can be said to lie hidden behind the surface appearance of the things which surround us.

Written within the fabric of nature is evidence of innumerable events that occurred in deep geological and evolutionary time in order for the volcanoes and orchids to exist, and it's only by means of years of collaborative investigation and ingenious new techniques, that we have come to be able to detect and decipher them.

As geologists diagram the molten roots beneath the rock on which Chusa wandered, and geneticists piece together the genetic roots which underlie each of Chusa's orchids, we have come to realise that these structures stretch backwards through space and time in ways that Chusa could never have imagined.

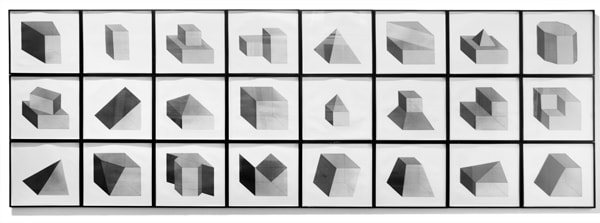

Below are high resolution images of each finished drawing, which can be viewed in detail using the control icons to the right of each image. Beneath these are a collection of Chusa's own orchid paintings, which now comprise a digitized collection available online here as part of Google's Arts and Culture Project.

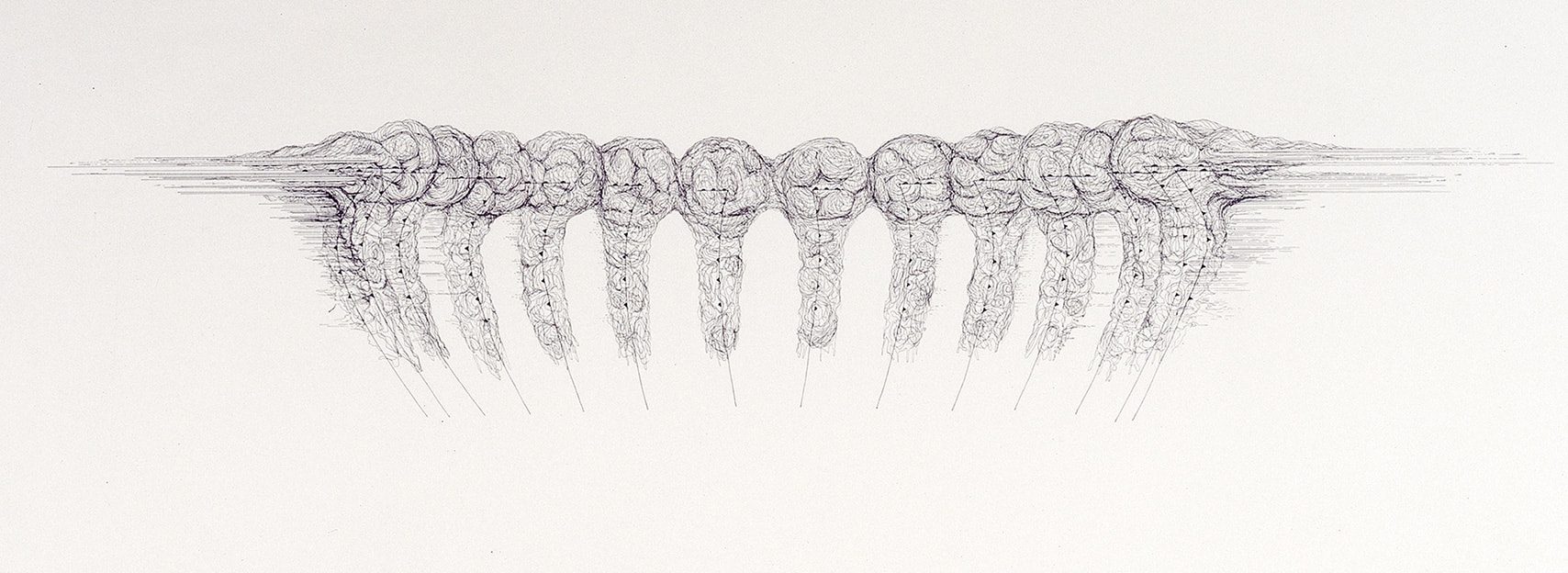

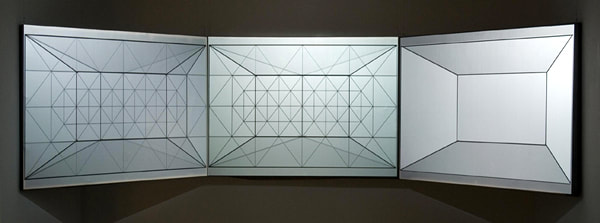

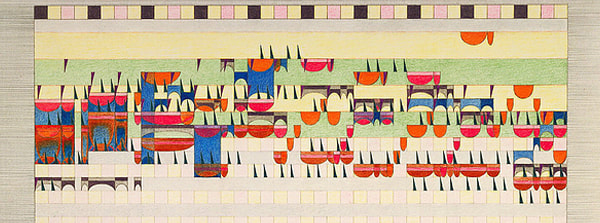

Tear glands, tear ducts, tear drops

(Lacrimal gland and ducts with Lithospheric anomalies)

Michael Whittle, 2019, Ink pencil and watercolour on paper, 111.2 x 78.9 cm

Jung-Hun Song et.al., 2018, Imaging of Lithospheric Structure Beneath Jeju Volcanic Island by Teleseismic Traveltime Tomography, Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 10.1029.

Online: https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JB015979

The roots of the Orchid

(Divergent phylogenetic tree with common ancestor and desiccation)

Michel Whittle, 2019, Ink pencil and watercolour on paper, 111.2 x 78.9 cm

Guo-Qiang Zhang et.al., 2017, The Apostasia genome and the evolution of orchids. Nature 549: 379-383

Online: https://rdcu.be/bUj7h

Chusa's Orchids:

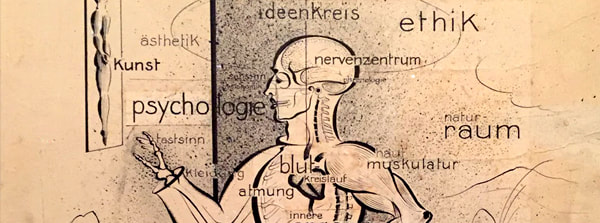

The limitations of the human senses and of human thought are interests that connect not only the works in that particular exhibition, but the majority art that I've produced over the last 10 years. Other common themes include our attempts to classify and comprehend the world around us, taking into account our biological limitations, and, most importantly, the dissonance that arises from our division of existence in to the subjective inner world of experience and an objective outer world of physical reality.

As an undergraduate student of Biochemistry, I was summoned by the head of the department to his office after our end of year examinations, where he cautioned me against my use of adjectives such as 'subtle', 'intricate' and 'profound' in an essay on molecular biology. Science, I was told, was like a game of cricket, which relies upon everyone playing by the same rules. Subjectivity, it turns out, was to be avoided at all costs in the context of a Biochemistry examination.

Five years later at the Royal College of Art, the vice chancellor, himself a former Biochemist, described my entry for the 2003, RCA Christmas card competition as too 'cold', 'clinical' and 'objective', but decided to award it second prize anyway out of curiosity.

It took a while to realise the deeper connection between these two seemingly unrelated events, but they were my earliest first hand experiences of the great divide between scientific objectivity and artistic subjectivity, and it wasn't until I created 'Clouds, glands, tributaries' in 2007, that I felt I had struck a balance between these two philosophical ideals, and possibly found a way to combine them.

Over time I came to realise that the approach to creating drawing is almost identical to that writing of Japanese Haiku poetry. Unlike classical Chinese poetry, the Haiku poet must remain entirely objective whilst composing the three short lines of the poem. In a classic 'show, don't tell' fashion, if a poet makes the mistake of revealing their subjective feelings too directly then the poem fails as a haiku.

To my mind the true power of a haiku lies in the 'subjective void' left by the poet for readers to fill themselves. As a result, the effect of a successful haiku is fleeting but powerfully subjective, and much more than the sum of its objective observations. The best haiku, even in translation, are capable of subjectively connecting reader and writer across vast distances in time, space, culture and language, despite the suppression of subjective expression in favour of objective depiction.

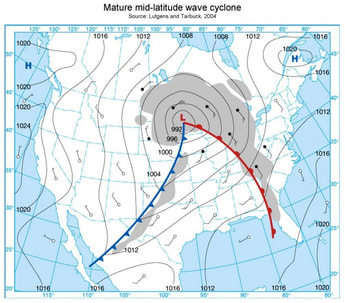

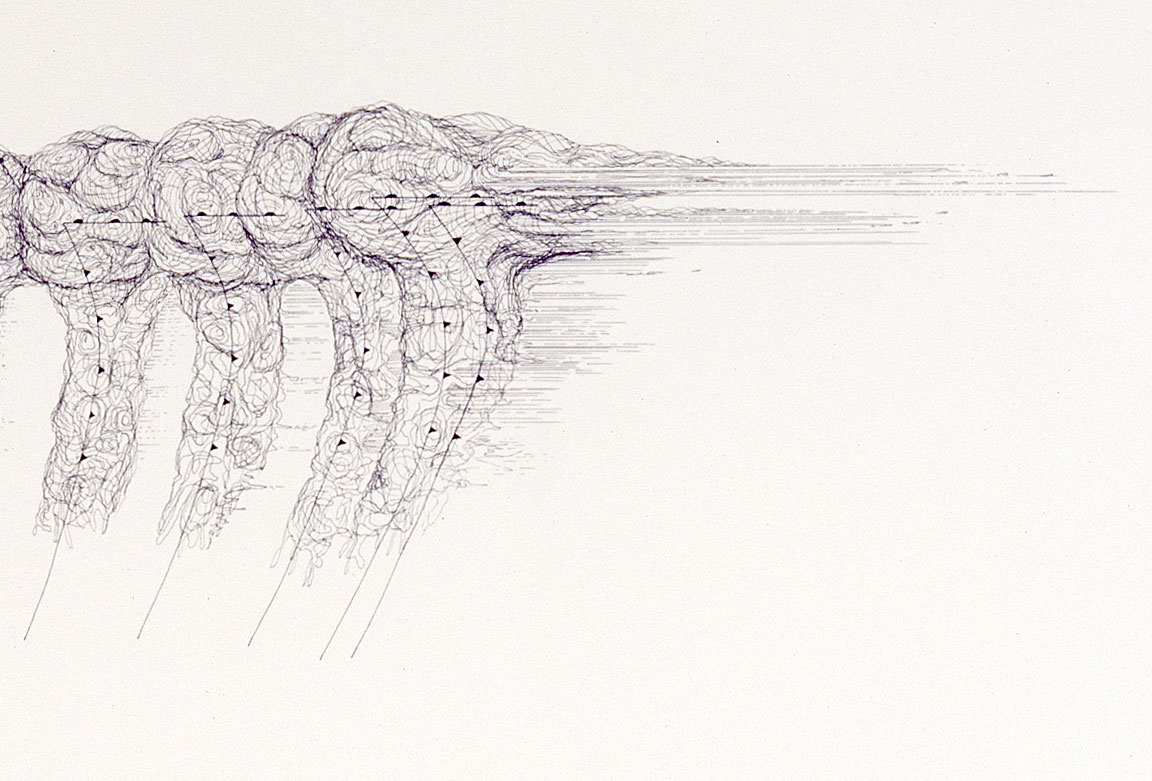

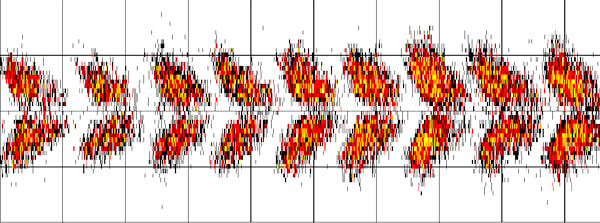

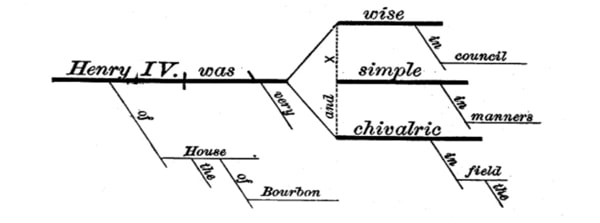

14 cyclones rotating towards the viewer, drawn as weather diagrams

| The cloud images are based on weather diagrams and employ the symbols for ‘cold front’ (colder air moving in the direction the triangles are pointing) and ‘warm front’ (warmer air moving in the direction the semicircles are pointing). Whereas weather diagrams depict such formations as maps viewed from above (i.e. by satellite imagery), in the drawing the clouds are positioned upright so that the cyclones rotate inwards toward the viewer. | Image 3: Mature mid-latiude wave cyclone Source: Lutgens and Tarbuck, 2009 |

Collision of cold front and warm front as part of the formation of a cyclone

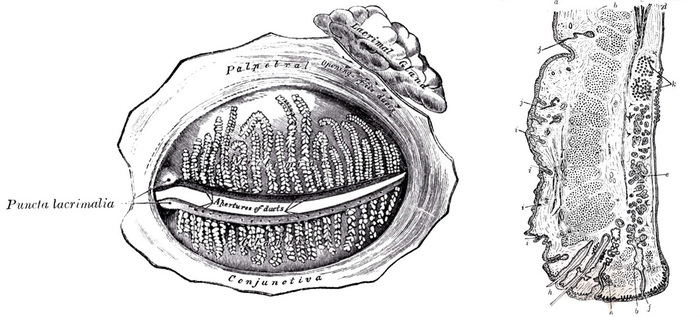

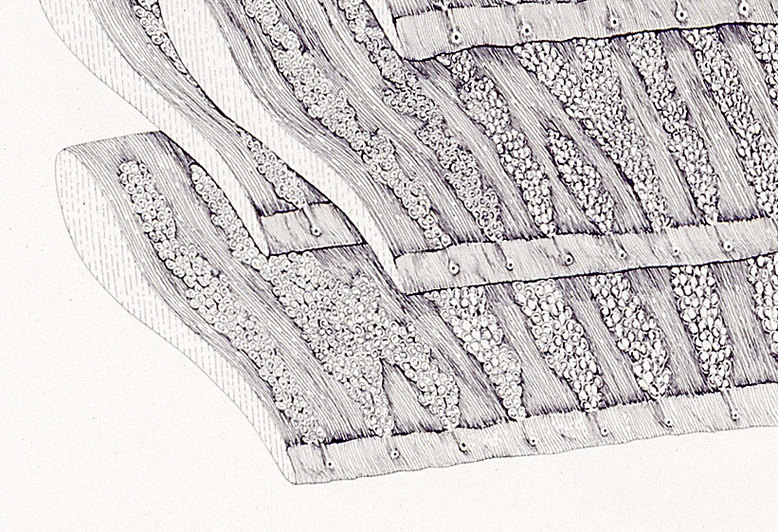

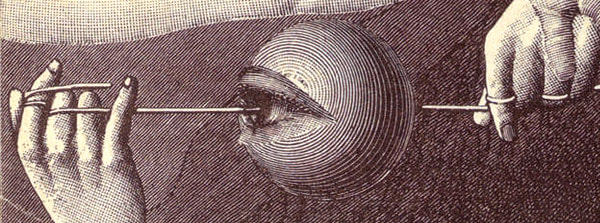

four inner eyelids complete with Meibomian (tarsal) glands

and also the Lacrimal gland which creates tears. (frontal view and cross section)

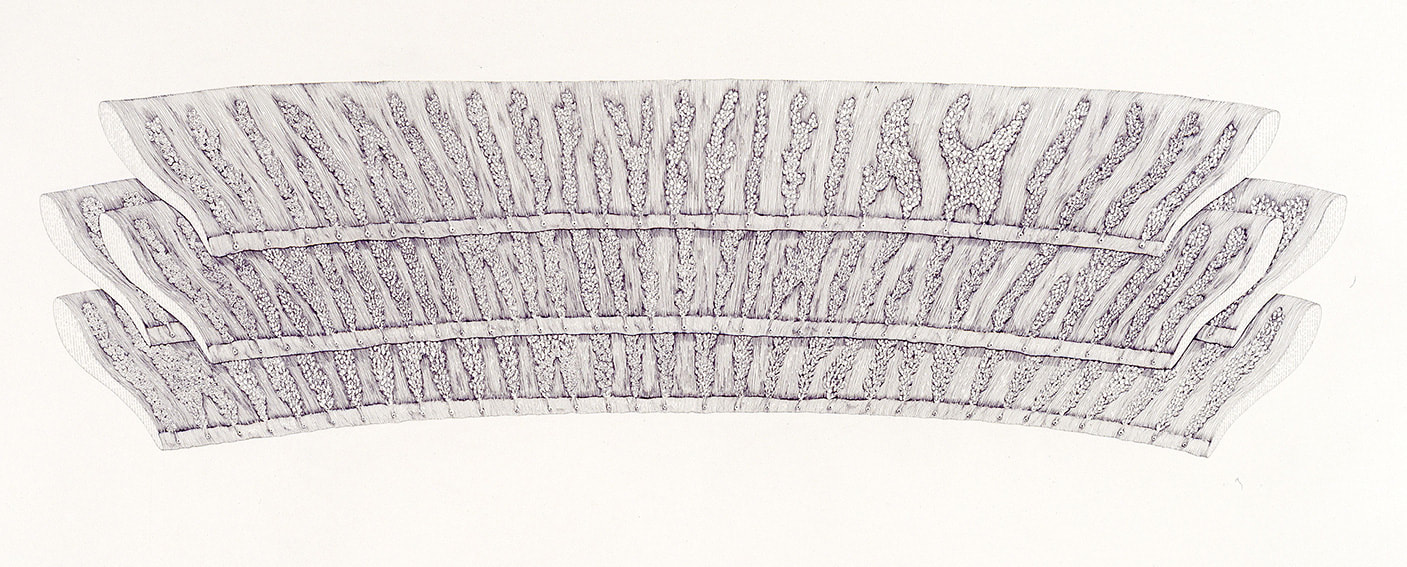

Inner upper eyelids complete with meibomian (tarsal) glands and ducts

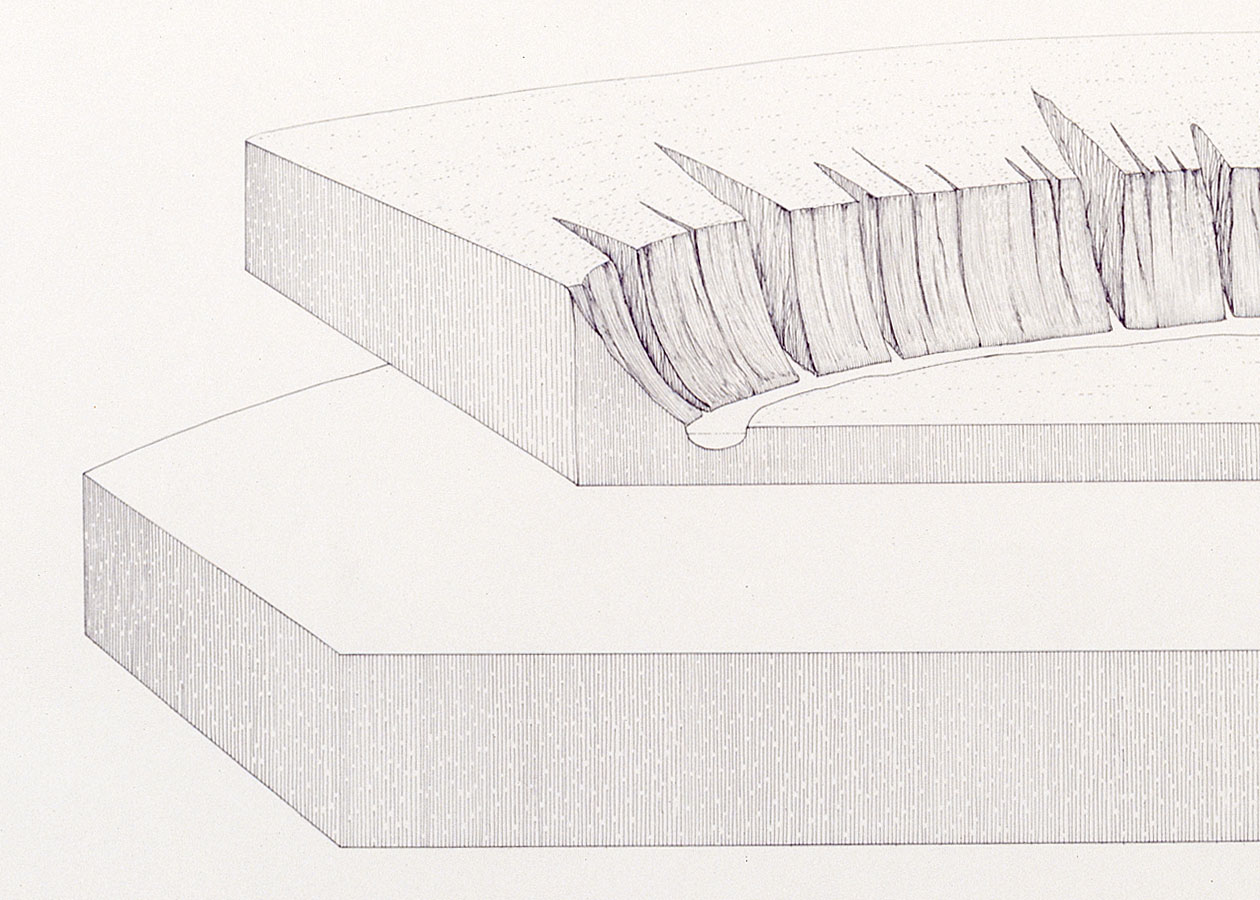

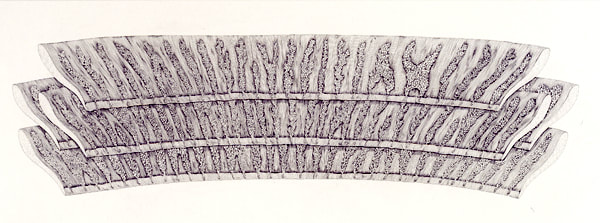

diagram depicting the theory of river tributary formation and flood plain

The drawings are based on the geological theory for the formation of river tributaries which suggests that over a period of geological time, small irregularities in the valley wall are eroded by running water to create fissures that gradually extend back into the surface of rock face into vast and complex river networks.

diagram depicting the theory of river tributary formation

The Meibomian / Tarsal glands secrete an oil that traps the 'tear film' against the surface of the eye. This creates a miniscule layer of salt water 0.003 mm thick, through which we view the world. The geological layer beneath this depicts an erosion pattern arising as a result of water draining from the land into a river system.

Two other aspects of water are present only by suggestion, the raindrops from the storm clouds and tears from the eyes, and both of these play off the idea of erosion over time on the landscape beneath. The spherical ball of an eye is also suggested by the spherical, negative space created by each of the three layers, in particular the four, overlapping, upper eyelids.

To use Umberto Eco's terms, 'Clouds, glands, tributaries' is an open work in with no definitive reading. Like Marcel Duchamp's 'Large Glass' ('The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even'), the title provides important clues but specific details remain hidden unless the viewer has some knowledge in meteorology, biology or geology.

Duchamp proposed thought of a painting's title as "another colour on the artist’s palette", and his use of obscure references in 'The Large Glass' was accompanied by volumes of notes published both during his lifetime and afterwards as an encyclopaedic reference system to 'The Large Glass'. The disconnected and vague nature of the notes however only acts to add yet another layer of abstract meaning to be deciphered, as part of a cryptic game that has occupied a whole generation of Duchamp scholars.

'Clouds, glands, tributaries' relies upon specialised knowledge to recognise the specific nature of the diagrams being used as the title gives no suggestion as to what type of cloud, gland or tributary the viewer is looking at, so that the references risk being lost in ambiguity.

In order to avoid this problem the titles of later works employ more specific scientific terminology, to act as a set of keys to access the concepts being referred to. Instead of having to refer to volumes of notes to read each drawing however, an inquisitive viewer can check the terms used in a title using their smartphone, and in this way each person can develop their own reading of a work and draw their own conclusions, thanks to the ever increasing intelligence of search engines, and the vast, interconnected hypertext of the internet.

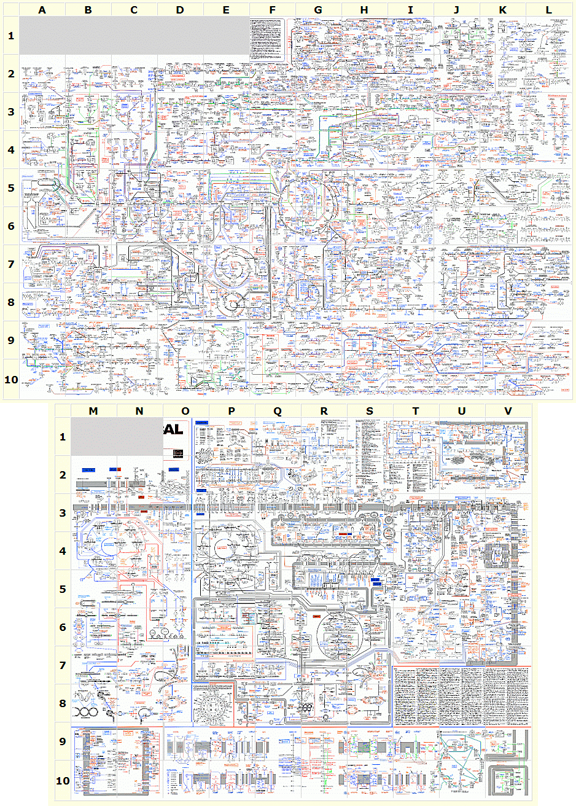

To see just how subtle, intricate and profound biochemical pathways really are, it's worth following the link below to two of my favourite diagrams of all times. Compiled by Gerhard Michal of the Boehringer Mannheim company, they were originally published as huge wall posters, but are now available for free in an online, interactive form.

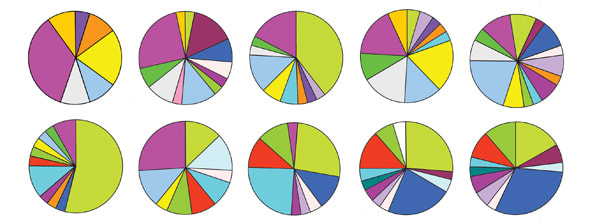

The two charts 'Biochemical Pathways' and 'Cellular and Molecular Processes', are both daunting in their scale and beauty, but it's worth remembering that if every known molecule within the human cell were to be included on a chart at this scale, it would need to be far larger than a football pitch in size (and probably 3-D).

Click on the images below to access the online versions of the charts:

Dr. Michael Whittle

British artist and

researcher based

in Macau

Categories

All

Alchemical Art

Anatomy

Arakawa And Gins

Architecture

Bauhaus

Contemporary-art

Contemporary-art

Duchamp

Genetics

Geology

Geometry

JMW Turner

Leonardo Da Vinci

Literature

Mathematics

Medieval Art

Musicology

Oskar Schlemmer

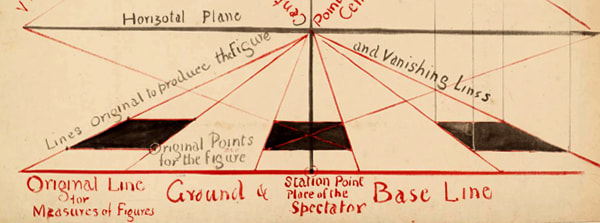

Perspective

Physics

Romanticism

Sol LeWitt

Surrealism

Theatre

Archives

April 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

June 2022

June 2021

August 2020

October 2019

August 2018

January 2018

November 2017

October 2017

April 2017

November 2016

October 2016

September 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016