The diagrams of geometry - part 2: A soggy book of diagrams as a wedding present from Marcel Duchamp10/20/2016

❉ This is the ninth in a series of blogs that discuss diagrams and the diagrammatic format, especially in relation to fine art. I recently completed my PhD on this subject at Kyoto city university of the arts, Japan's oldest art school.

Feel free to leave comments or to contact me directly if you'd like any more information on life as an artist in Japan, what a PhD in Fine Art involves, applying for the Japanese government Monbusho scholarship program (MEXT), or to talk about diagrams and diagrammatic art in general.

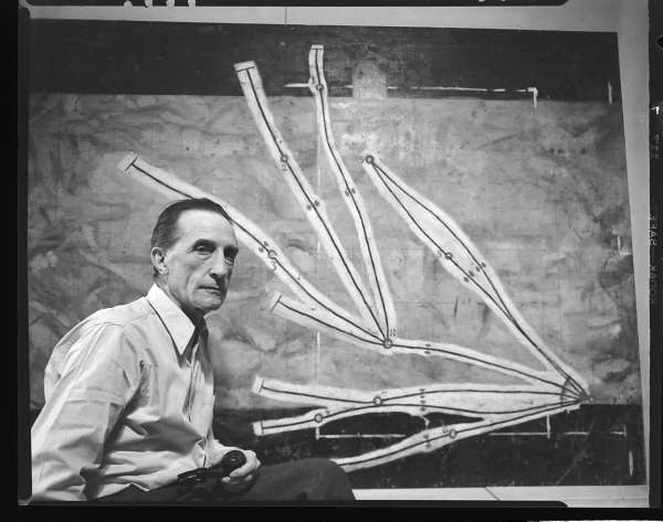

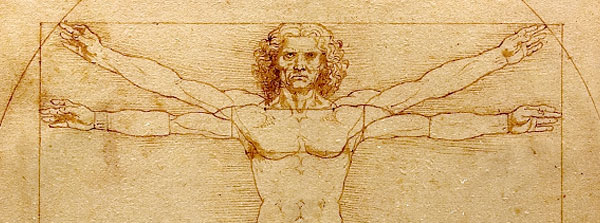

Figure 1: Portrait of Marcel Duchamp for Life Magazine taken in 1952 by Gordon Parks,

in front of Network of Stoppages (1914), Oil and pencil on canvas, 148.9 x 198.12 cm

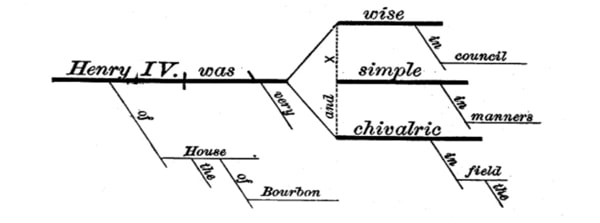

The young modernist poet, dramatist and writer Jacques Nayral (a pseudonym for Joseph Houot) wrote the forward to the catalogue for the 1912 exhibition of Cubist art "Exposicion d'art cubista" at the Dalmau Gallery in Barcelona. Nayral described how “[t]he Mathematical spirit seems to dominate Marcel Duchamp. Some of his pictures are pure diagrams, as if he were striving for proofs and synthesis.” (1)

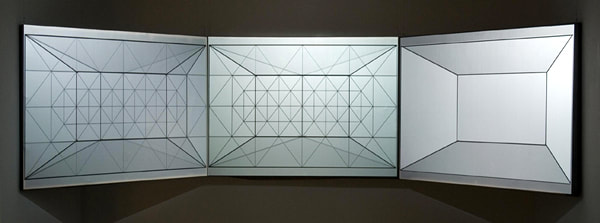

We have already seen in a previous post how Duchamp's training as a young artist was founded upon the diagram, having studied during a period in France when students were made to practice mechanical drawing as opposed to the traditional historical modes of figurative and landscape. Trained in ‘the language of industry’, (2) Duchamp remained fascinated with the detached, objective qualities of technical diagrammatic drawings, proclaiming his desire to create “paintings of precision” with a “beauty of indifference.” (3) He also spoke in interview of how he wished to "go back to a completely dry drawing, a dry conception of art. I was beginning to appreciate the value of exactness, of precision and the importance of chance… And the mechanical drawing was for me the best form of that dry conception of art… a mechanical drawing has no taste in it. (4)

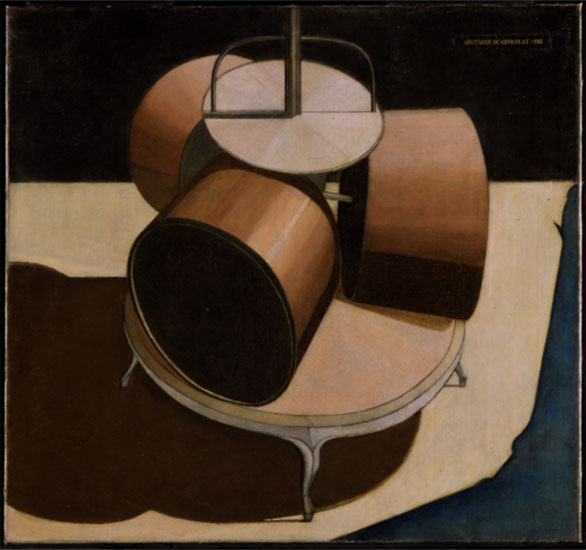

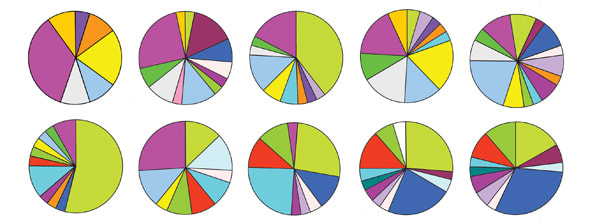

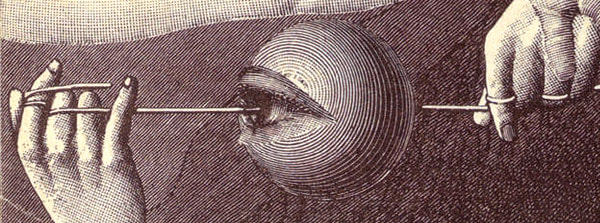

The steps Duchamp took to refine his work towards being beautifully indifferent images of precision are visible in the two paintings above, made within a year of each other. Chocolate grinder number 1 (1913) is painted in traditional perspective and the illusion of three dimensionality also relies upon its strong shadows and graded colouration. On the other hand in Chocolate grinder number 2, the object is depicted in what could be described as a conceptual landscape: a neutral and shadow free environment of flat colour and a strict one point perspective. Despite his fascination with the diagram Duchamp continued to seek out new ways to subvert this mechanical, ‘anti-expressive’ system of geometrical depiction on a number of levels, such as his attempts to incorporate chance and chaos in to his artistic process. In "Three standard stoppages", the artist claims to have dropped metre long pieces of string from a height of one metre and traced the outline they made upon landing. These shapes were then cut out of strips of wood and presented in a box as a set of alternative, two dimensional standard metre lengths.

Figure 4: Marcel Duchamp, 3 stoppages étalon (3 Standard Stoppages),

1913–4, replica 1964, Wood, glass and paint on canas, 400 x 1300 x 900 mm

Asked what he considered to be his most important work, Duchamp replied that "As far as date is concerned I'd say the Three Stoppages of 1913. That was when I really tapped the mainspring of my future. In itself it was not an important work of art, but for me it opened the way - the way to escape from those traditional methods of expression long associated with art … For me the Three Stoppages was a first gesture liberating me from the past.' (5)

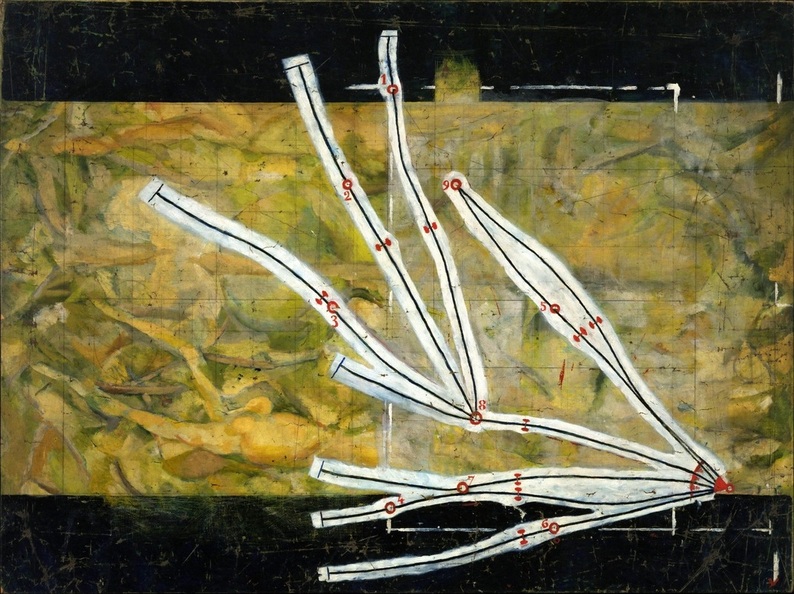

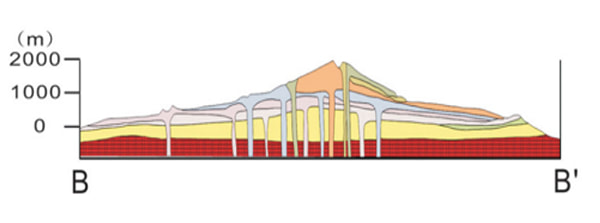

It is important to take into account what was happening within the world of science at the time these works were being made, and Duchamp's active interest in the popular science books of the time. In "Science and Hypothesis" (1902) for example, the mathematician, theoretical physicist, engineer, and philosopher of science Henri Poincaré posed the question of whether or not it would be 'unreasonable to inquire whether the metric system is true or false?'. At almost the same time, two other noteworthy figures Hermann Minkowskiand Albert Einstein were already setting about redefining our most basic understanding of the very geometric fabric of reality for the first time in well over 2000 years. (6) Also of special interest to Duchamp at that time was the work of the French humorist Alfred Jarry (1873-1907), creator of Pataphysics, or the 'science of imaginary solutions'. Jarry developed this imaginary subject to "examine the laws governing exceptions, and … explain the universe parallel to this one", and it is easy to see how Duchamp was drawn to such a novel, humorous and profoundly revealing idea with its suggestions of alternative realities with their own physical laws. (7) The wooden templates of Duchamp's "diminished metres" were later used to design the pattern of lines in his painting "Network of Stoppages" (Reseaux des stoppages), shown below.

Figure 5: Marcel Duchamp, Network of stoppages (Reseaux des stoppages),

1914, oil and pencil on canvas, 198 x 149 cm

The networks are depicted on top of what appears to be a replication of Duchamp's earlier painting "Young Man and Girl in Spring", oil on canvas, 1911, albeit rotated through ninety degrees. This is a subtle contrast of cold chance diagrammatically visualised against the image of a symbolic fertility rite or creation myth.

The large glass subverts the dry, mechanical visual language of objectivity by applying it to subjects that it wasn't designed to address, namely the psycho-sociology of human courtship and sexuality, or what would previously have been called romanticism. [Due to the complexity and art-historical importance of The Large Glass and its accompanying notes, it will be covered in a future post dedicated to that work alone.]

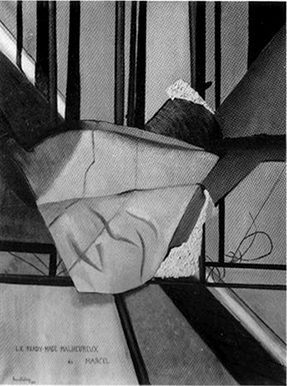

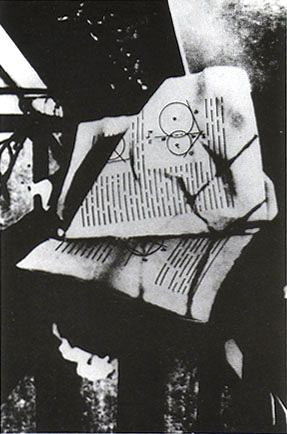

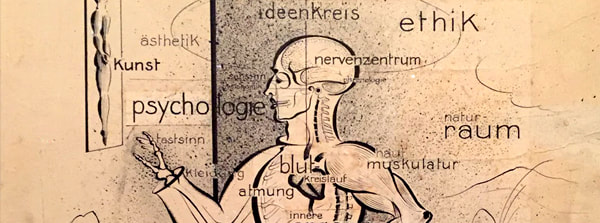

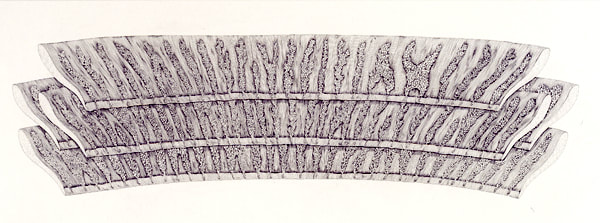

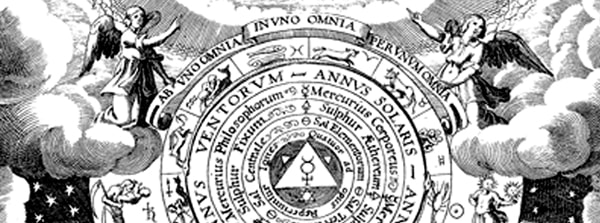

An often overlooked work that questions our notions of ideal forms in geometry with a poetic pathos is Unhappy Readymade, a so called 'assisted readymade' created by Duchamp around 1919 (See figures below).

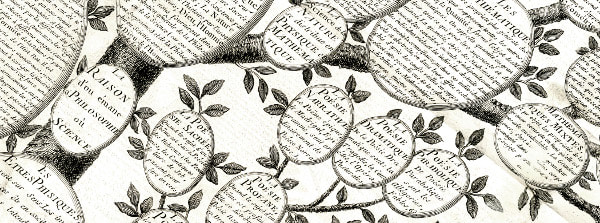

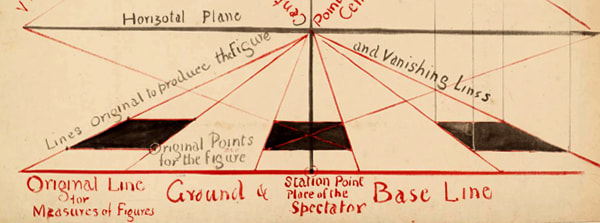

Foreshadowing the production processes of Sol LeWitt, Unhappy Readymade consisted of a simple set of instructions sent by post as a wedding gift to his sister Suzanne Duchamp and the artist Jean Crotti, so that, in the words of LeWitt, “the Idea becomes a machine that makes the art.” (8) In an interview with Pierre Cabanne, Duchamp described his instructions for Crotti to buy a "…geometry book which he had to hang by strings on the balcony of his apartment in the rue Condamine; the wind had to go through the book, choose its own problems, turn and tear out the pages. Suzanne did a small painting of it, ‘Marcel’s Unhappy Readymade.’ That’s all that’s left, since the wind tore it up. It amused me to bring the idea of happy and unhappy into readymades, and then the rain, the wind, the pages flying, it was an amusing idea… " (9)

Duchamp’s unhappy readymade sets out to highlight the contrast between ideal geometric forms which exist only as concepts, their manifestation as token textbook diagrams of ink on paper and the results of weathering on the text book.

The Duchamp scholar Linda Dalrymple Henderson points out that this was in fact one of the artist's last specific comments on geometry, and that the book used was a copy of Euclid’s elements so that, ironically, the plane geometry of Euclid was in contrast to damage caused by the wind and rain producing distortions in the diagrams as “non-Euclidean deformations of the Euclidean geometries in the text.” (10) In a letter to his sister, Duchamp wrote: “I liked the photo very much of the Ready Made sitting there on the balcony. When it all falls apart you can replace it.” (11) Duchamp also suggests that this is a lesson to be repeated, a reminder of the fundamental difference between an essentialised, idealised, conceptual landscape of perfect forms, and the chaotic nature of decay and change, which composes our everyday experience of the real world. Some years later Duchamp told one interviewer that “he had liked disparaging ‘the seriousness of a book full of principles,’ and suggested to another that, in its exposure to the weather, ‘the treatise seriously got the facts of life’”. (12)

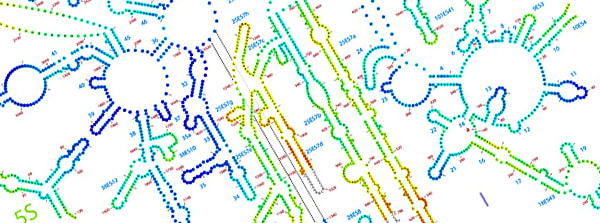

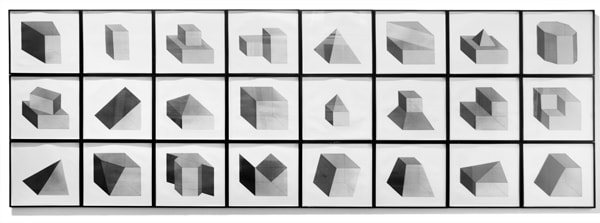

Below is a scanned reproduction of the British, Victorian mathematician Oliver Byrne's 1847 edition of Euclid's Elements. Created almost a century before the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian made geometrical red, yellow, and blue lines so famous, Byrne titled his edition "The First Six Books of the Elements of Euclid in Which Coloured Diagrams and Symbols Are Used Instead of Letters for the Greater Ease of Learners".

Downloadable copies are available in various formats courtesy of an Internet Archive at the University of Toronto Libraries here: Downloadable formats Or as a pdf here: Downloadable pdf. Click on the pages of the book below to turn them: Oliver Byrne (1810–1890) was a civil engineer and prolific author of works on subjects including mathematics, geometry, and engineering. His most well known book was this version of ‘Euclid’s Elements’, published by Pickering in 1847, which used coloured graphic explanations of each geometric principle. The book has become the subject of renewed interest in recent years for its innovative graphic conception and its style which prefigures the modernist experiments of the Bauhaus and De Stijl movements. Information design writer Edward Tufte refers to the book in his work on graphic design and McLean in his Victorian book design of 1963. In 2010 Taschen republished the work in a wonderful facsimile edition. ( Wikipedia link )

References:

1) Nayral, J. (1912) preface to Galeries J. Dalmau, Barcelona. Exposció de Arta cubista. (April – May 1912) Reprinted in Guillaume Apollinaire: Les Painters Cubistes. Breunig, L.C., Chevaliare J. Cl. Paris: Hermann (1965) p. 181 2) Nesbit, M. (1991) The Language of Industry. In: The Definitely Unfinished Marcel Duchamp. De Duve, T. (Ed.) Massachusetts: Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1991. pg.356. 3) Duchamp, M. Salt Seller: The writings of Marcel Duchamp (Marchand du sel). Eds. Sanouillet, M. Peterson, E. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973. p. 30. 4) Duchamp, M. As quoted in Sweeney, A conversation with Marcel Duchamp, NBC Television interview, January 1956. Sweeney, J.J. (1946) Eleven Europeans in America: Marcel Duchamp. Museum of Modern Art Bulletin 13, p. 19-21. In: Dalrymple Henderson, L. (1998) Duchamp in context: Science and technology in the large glass and related works. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 5) Duchamp, quoted in: Katherine Kuh, The Artist's Voice: Talks with Seventeen Artists, New York 1962, p.81. 6) Henri Poincaré quoted in: Herbert Molderings, 'Objects of Modern Scepticism', in Thierry de Duve (ed.), The Definitively Unfinished Marcel Duchamp, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1991, pp.243-65, reproduced p.247 Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, revised and expanded edition, New York 1997, pp.594-6, reproduced pp.594, 595, 596 7) Alfred Jarry quoted in: Dawn Ades, Neil Cox and David Hopkins, Marcel Duchamp, London 1999, pp.78-9, reproduced p.78 8) LeWitt, S. (1967) Paragraphs on Conceptual Art. Art Forum. June, 1967 9) Cabanne, P. (1971) Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp. Originally published: London: Thames and Hudson. p. 61. 10) Dalrymple Henderson, L. (2013) The Fourth Dimension and non-Euclidean geometry in Modern Art. 2nd Revised Edition. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. p. 283. 11) Duchamp, M. (1920) Letter to Suzanne Duchamp. In: Affectueusement, Marcel: Ten Letters from Marcel Duchamp to Suzanne Duchamp and Jean Crotti. (1982) Francis Naumann, M. Archives of American Art Journal, Vol. 22, No. 4. pp. 2-19. 12) Tompkins, C. (1998) Duchamp: A Biography. New York: Henry Holt and Co. Inc. p.212-214

1 Comment

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Dr. Michael WhittleBritish artist and Posts:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|