|

❉ This is the second in a series of blogs that discuss diagrams in the arts and sciences. I recently completed my PhD on this subject at Kyoto city University of the Arts, Japan's oldest Art School. Feel free to leave comments or to contact me directly if you'd like any more information on life as an artist in Japan, what a PhD in Fine Art involves, applying for the Japanese Government Monbusho Scholarship program (MEXT), or to talk about diagrams and diagrammatic art in general.

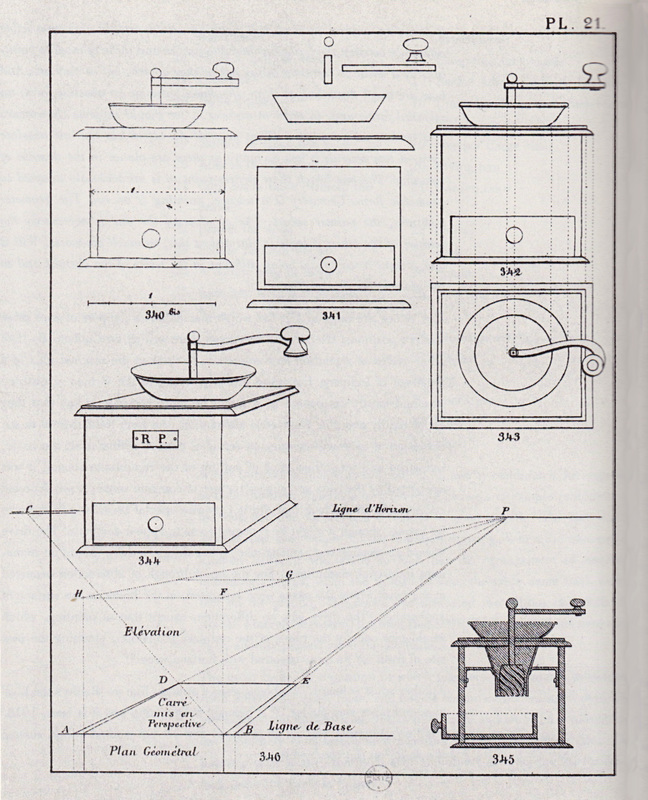

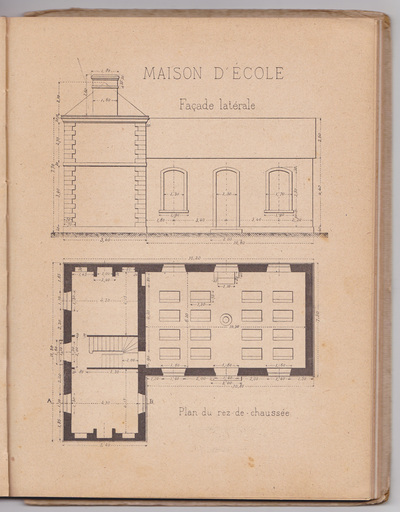

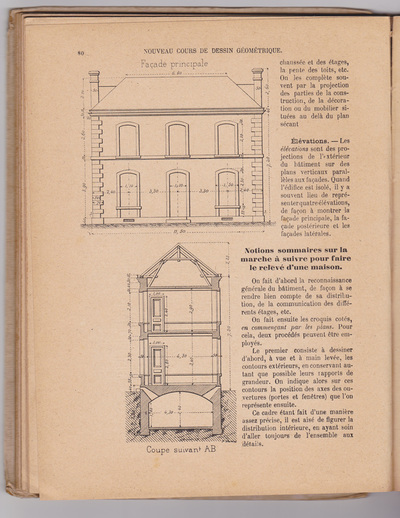

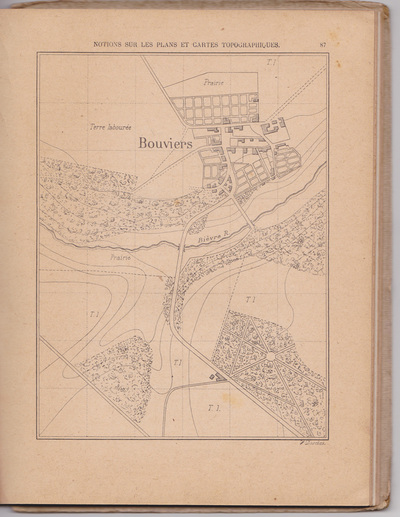

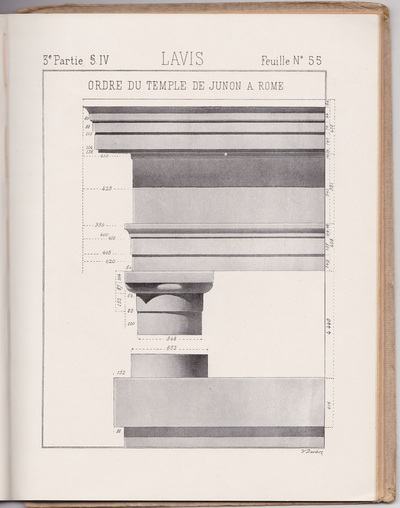

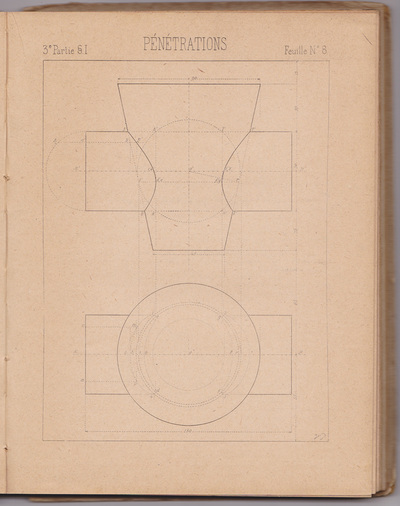

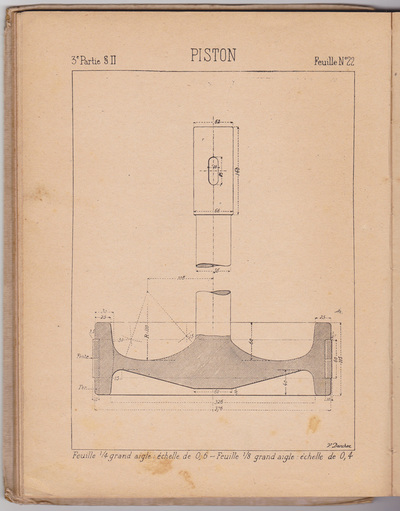

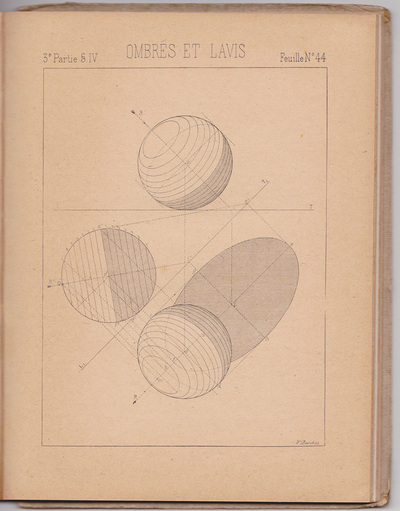

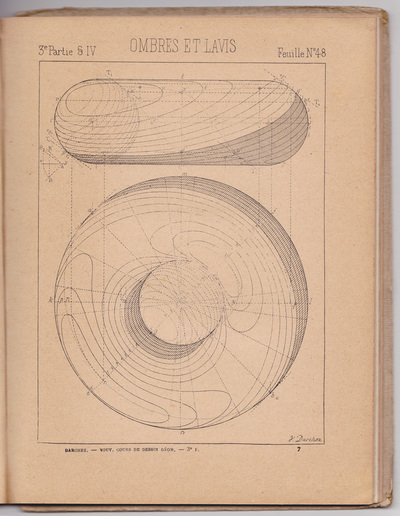

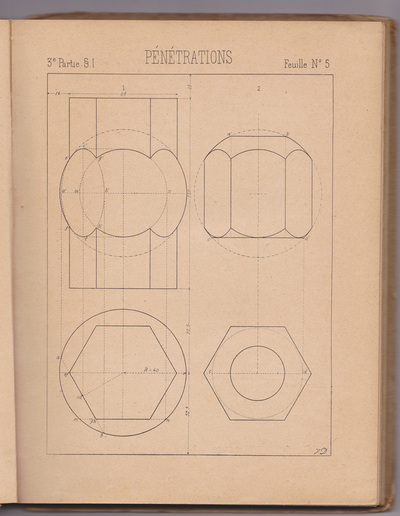

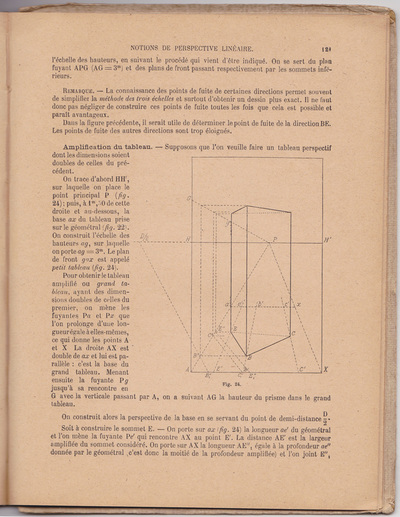

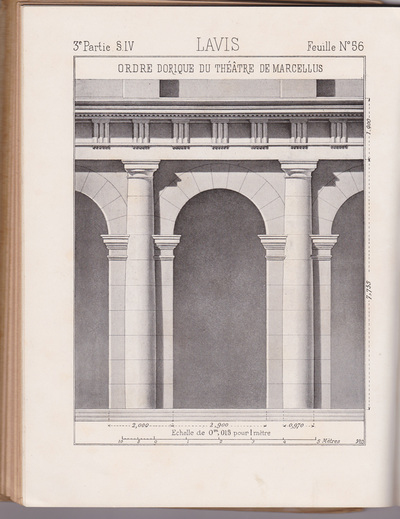

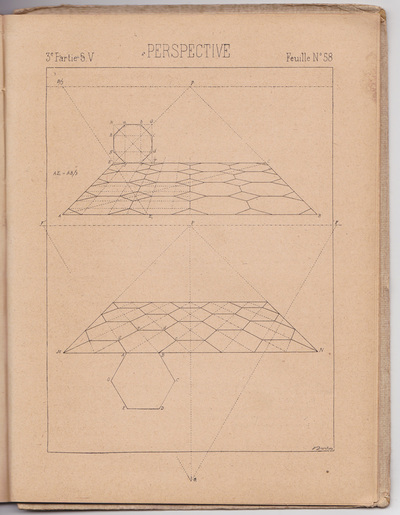

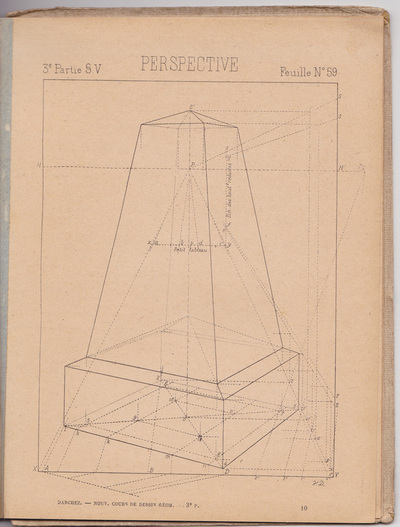

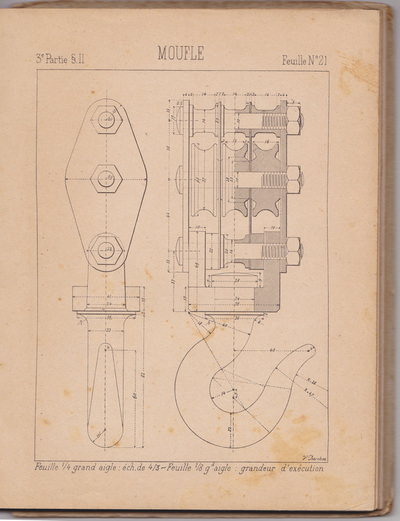

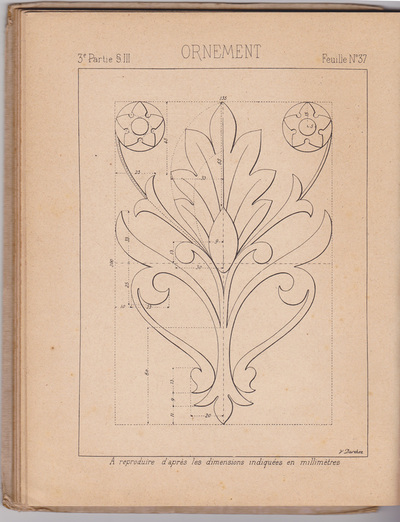

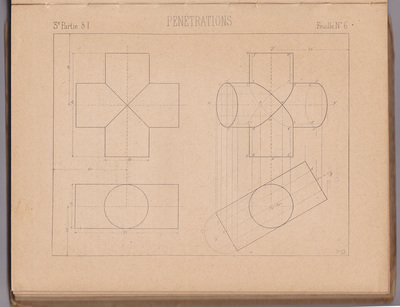

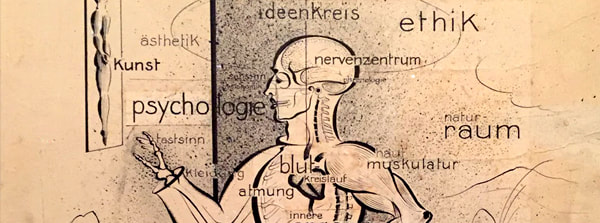

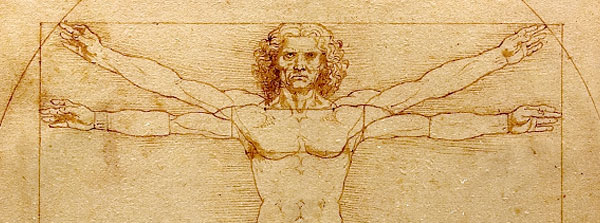

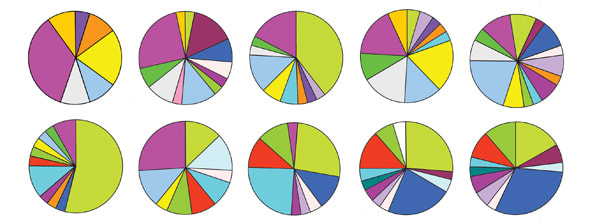

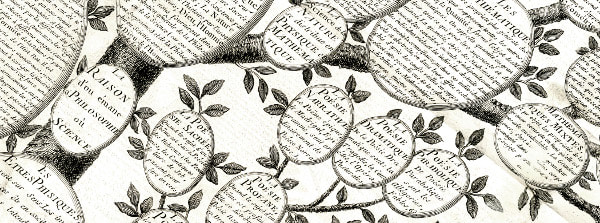

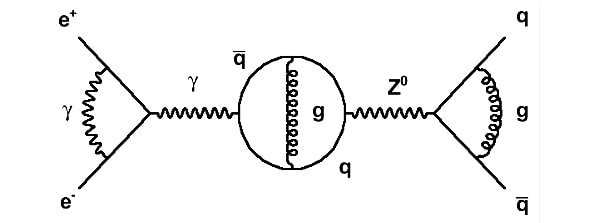

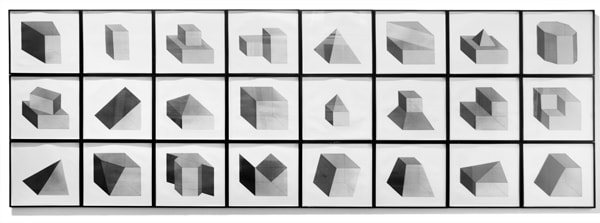

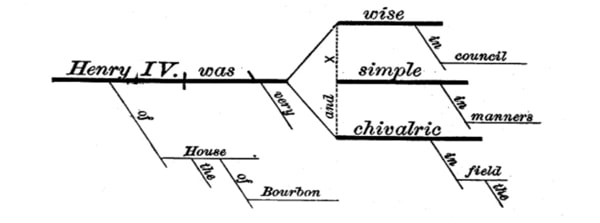

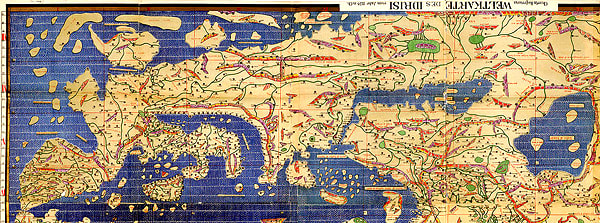

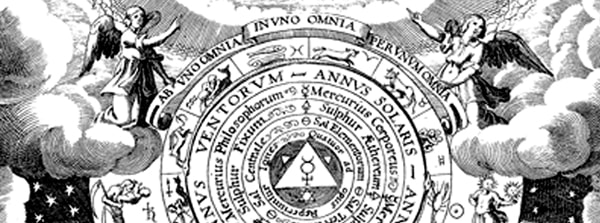

What would happen if you were to change the focus of an entire country's art education system from imitating nature and the human body to mastering the art of technical drawing and creating diagrams ? By the time the French artist Marcel Duchamp was born in 1887, the French national education system had undergone a systematic overhaul and just such changes were already in place in the art departments of each state funded public school. (1) Students of art were no longer expected to study and mimic classical sculpture, the old masters, or the art of the renaissance. Instead, the aim of the new curriculum was fluency in a measured, mechanical drawing style that was refined, skeletal and precise. Referred to as the 'language of industry', this was a whole-sale promotion of a new national, visual language of science, technology and culture in the age of mechanical production. In other words, second only to the epic encyclopedic projects of the 1700's, this was the new dawn of the diagram at the heart of French Culture. In her essay titled 'The language of Industry', Molly Nesbit describes how "by and large this was a language meant for work, not for leisure, and certainly not for raptures or poetic, high cultural sighs. This language was pre-aesthetic, a public culture based upon mechanical drawings, sans colour, sans nature, sans body, sans the classics, some would have said sans everything." (2) Within the class rooms, drawing courses were divided in to depicting objects in perspective (objects reproduced the way they appear to the eye) and in projection (objects depicted as ideal forms, independent of a human observer and the optics of our two human eyes). Because of this distinction, French art students were taught to make a fundamental distinction between apparent and true representation, just as Duchamp himself would later make a similar distinction between what he called retinal and non-retinal art.

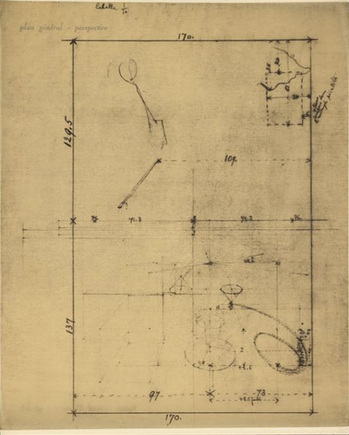

Marcel Duchamp went on to develop his artistic use of diagrams and diagramming in a number of important ways, from the one dimensional plumb lines that he dropped to make '3 standard stoppages' (a work which questions the one dimensional meter as a standard unit of length), to his intricate two dimensional sketches for 'The Large Glass' which suggest archetypal lines and platonic skeletal forms in higher dimensions.

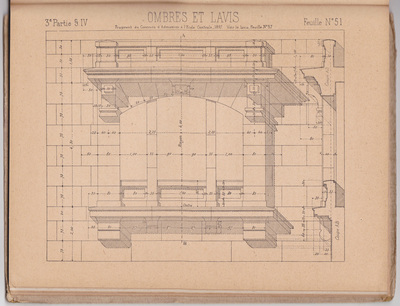

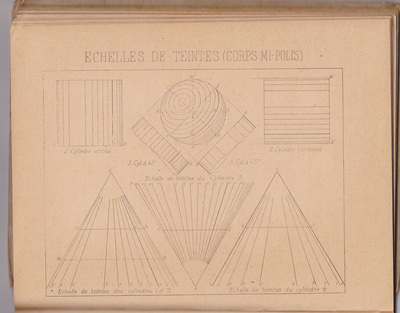

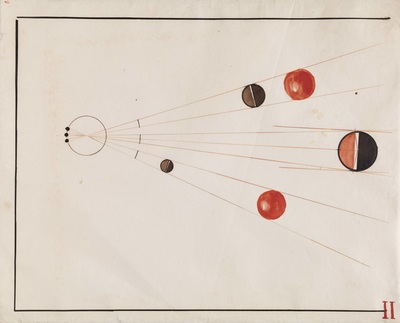

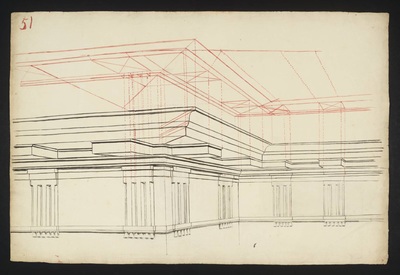

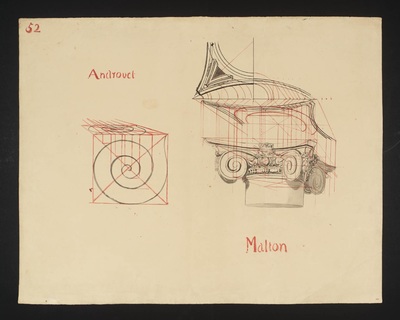

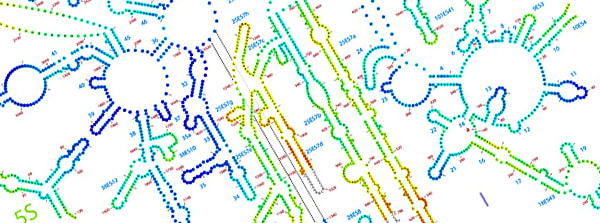

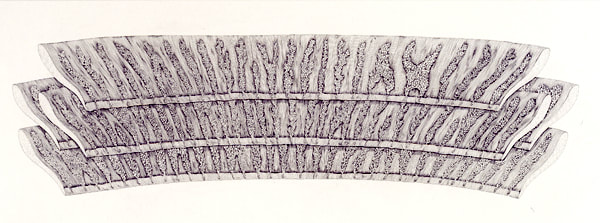

Duchamp's various projects embodied a more general shift in science and culture, from drawing as a representation of the natural world, to drawing as a means of depicting the technical nature of the structural and functional systems which underlie reality, as described by science and mathematics, but always by means of the diagram. The following diagrams were scanned from the third book in the series "Nouveau Cours de Dessin géométrique", compiled by Professor V. darchez of the state-funded secondary school in Lyon. The director of the Beaux-Arts School in Paris at the time, the sculptor and critic Eugène Guillaume, elaborated upon the new program of diagrammatic training: "Drawing is by its very nature exact, scientific, authoritative. It images with undeniable precision (to which one must submit) things such as they are or as they appear. Not one of its configurations could not be analyzed, verified, transmitted, understood, realized. In its geometrical sense, as in perspective, drawing is written and is read: it has the character of a universal language." (6) References:

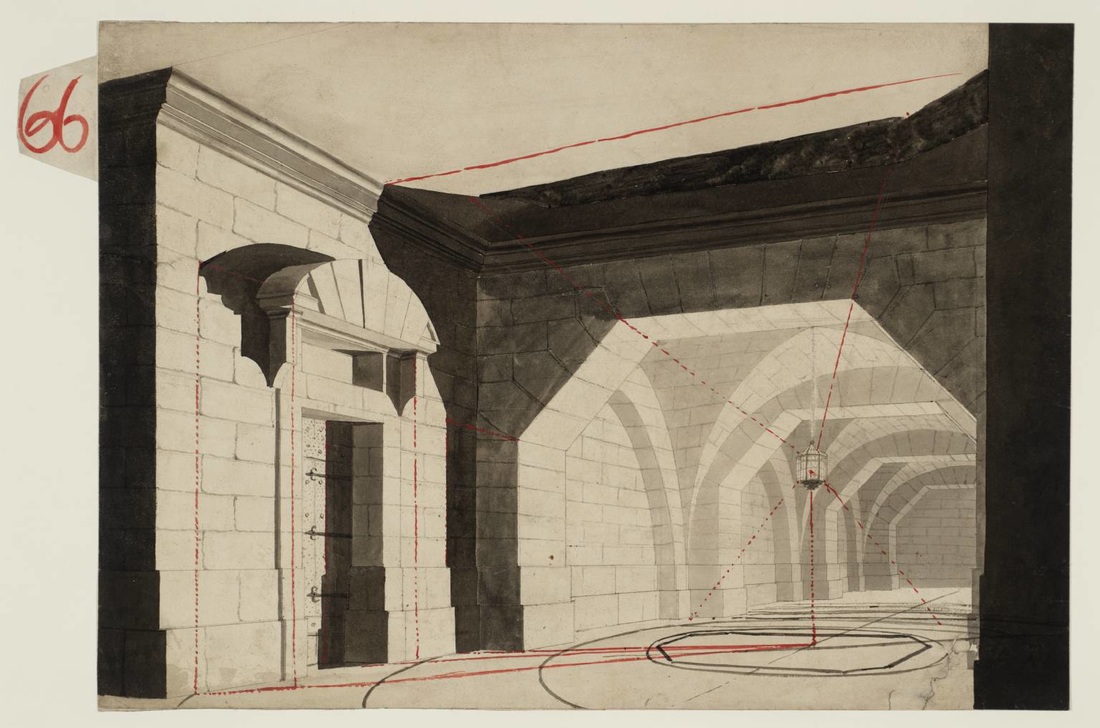

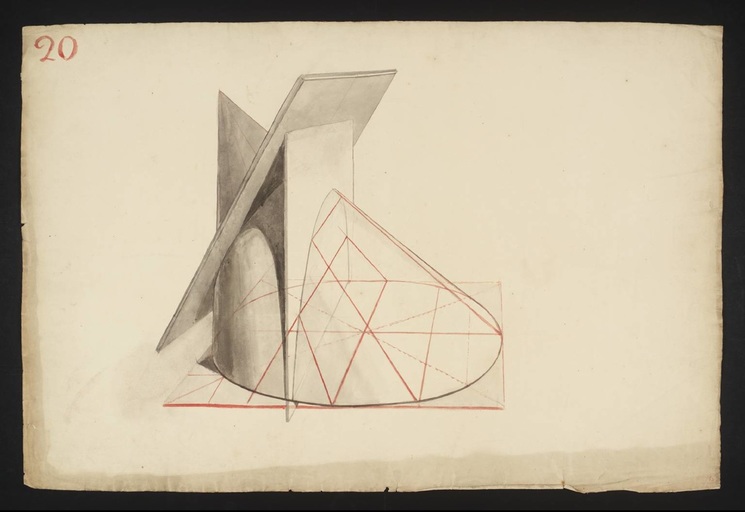

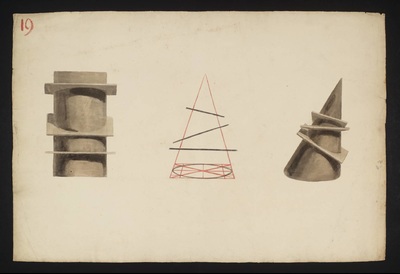

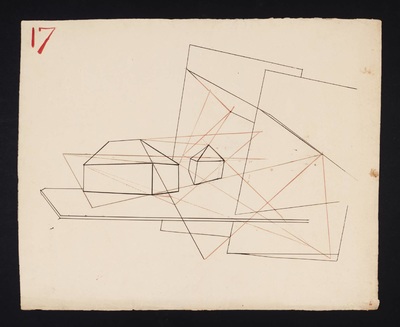

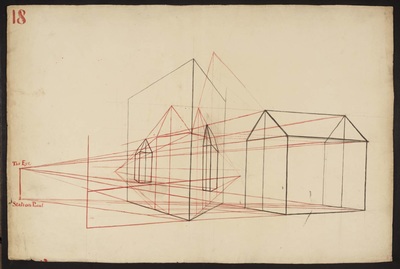

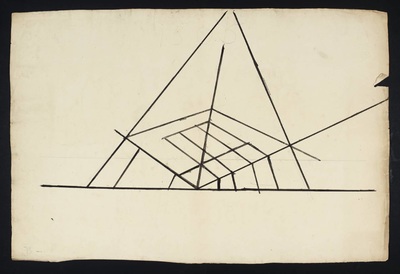

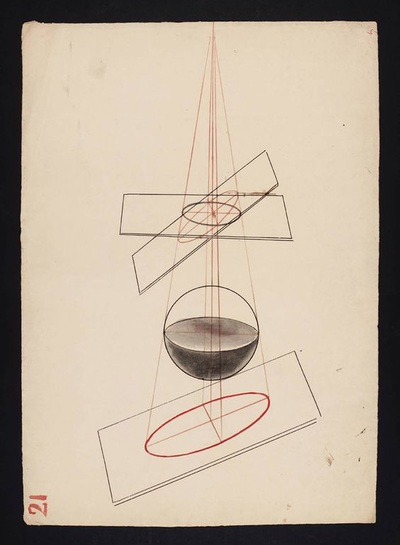

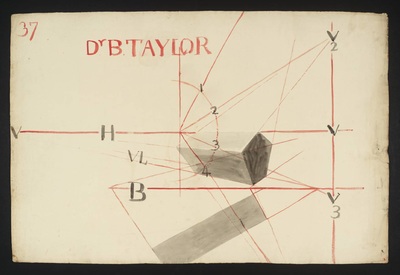

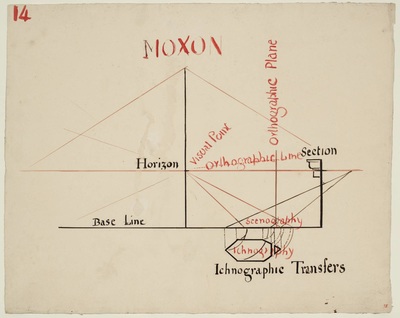

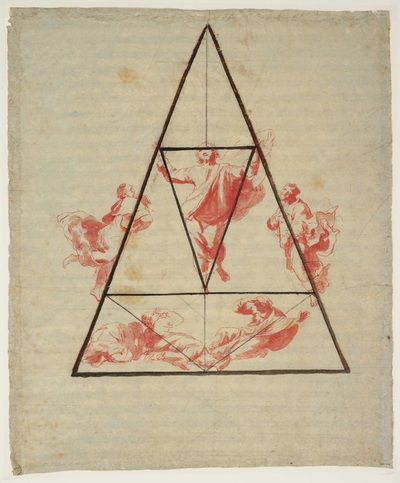

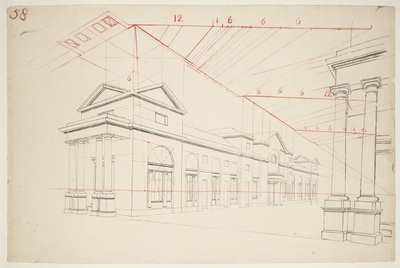

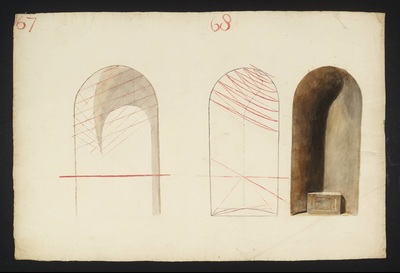

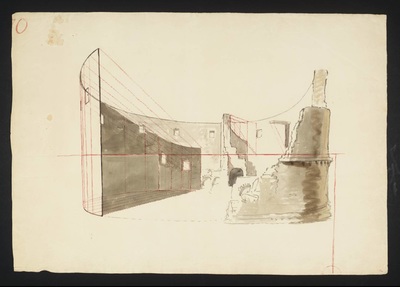

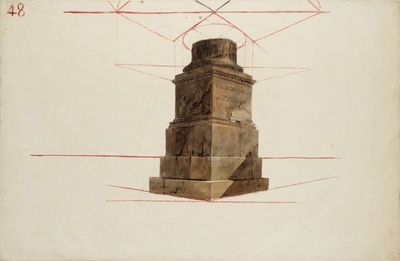

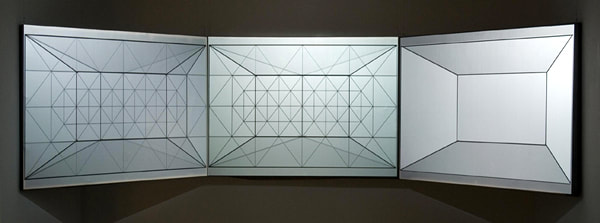

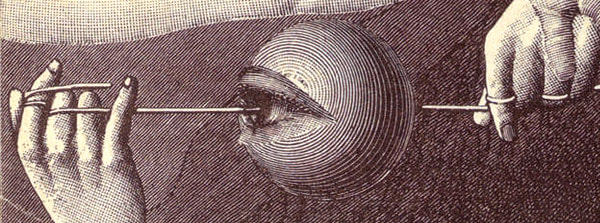

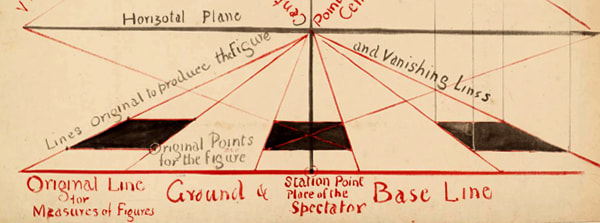

1) The 'Ferry Reforms' of the French national school system were established during the 1870s and 80s. 2) Nesbit, M. The Language of industry (1991). In: The Definitely unfinished Marcel Duchamp, MIT Press, 1991, p.356. 3) Duchamp, M. interview with Dorothy Norman, first published in Art in America, Vol.57, July -Aug. 1969. p38. 4) Duchamp, M. In: Schwarz, A. The Complete works of Marcel Duchamp, revised and expanded edition, New York, 1997, p.573. 5) Duchamp, M. In; Ades, D., Cox, N., Hopkins, D. Marcel Duchamp, london, 1999, p.75. 6) Nesbit, M. The Language of industry (1991). In: The Definitely unfinished Marcel Duchamp, MIT Press, 1991, p.372. ❉ This is the first in a series of blogs that discuss diagrams in the arts and sciences. I recently completed my PhD on this subject at Kyoto city University of the Arts, Japan's oldest Art School. Feel free to leave comments or to contact me directly if you'd like any more information on life as an artist in Japan, what a PhD in Fine Art involves, applying for the Japanese Government Monbusho Scholarship program (MEXT), or to talk about diagrams and diagrammatic art in general. Figure 1: Lecture Diagram 66- Interior of a Prison (after Giovanni Battista Piranesi) c.1810 The English Romanticist landscape painter Joseph Mallord William Turner held the position of Professor of Perspective at the Royal Academy for some thirty years, from 1807 - 1837. During this time he managed to deliver only twelve full lecture courses. Despite being primarily a landscape artist, Turner was in a position to lecture on perspective (principally an architectural specialisation) after having been apprentice to a master of the subject, the younger Thomas Malton, during the 1780s. Turner had also worked as a draughtsman to the architects Thomas Hardwick and James Wyatt, thus giving him a solid grounding in perspective theory and its practical application. The title of 'Professor of Perspective' was something Turner was particularly proud of, sometimes even adding ‘PP’ when signing works (1). Turner spent over three years preparing his lectures, and during this time created over 170 diagrams to be used as visual aids during his presentations. These drawings were large in size at approx. 60 x 90 cm (2ft x 3ft), and were positioned by assistants on a stand at his command. Figure 2: Lecture Diagram 20- Conic Sections (after Thomas Malton Senior) c.1810 Despite his radical brilliance as an artist, Turner's lectures were far from successful. Audience members complained of his mumbling disorganisation, the rapid rate at which his images were presented, or even of his ambitious attempt to show his complete set of diagrams as a complex diagrammatic backdrop to his lecture. Fellow Academicians mocked Turner for his 'inane lecturing style', his misuse of technical terms, vulgar pronunciation (he pronounced Mathematics as ‘mithematics’ ), and his liable to stray wildly from the subject he was supposed to be talking about (2,3). However the diagrams Turner created to elucidate the complexities of perspective that he struggled to explain verbally, remain even today refined, lucid and strikingly contemporary in appearance. They provide excellent examples of what the American Philosopher-Scientist Charles Sanders Peirce described as 'Moving Pictures of thought', in that one can literally see a given argument and experiment, model and confirm the ideas within ones own mind (4). As one of the students in attendance at his lecture later reported, Turner's diagrams ‘were truly beautiful, speaking intelligibly to the eye if his language did not to the ear’. (5) This Series of Diagrammatic drawings holds a fascinating position in art history, in that they were made by one of the preeminent Romantic Landscape painters of the period, and yet reveal a mastery of the objective and technical rules of optics and perspective. Turner, however, was an artist of his time, and in the words of Brian Lukacher, the ‘mathematical rules of perspective, he believed, crumble before the higher metaphysics of the artistic mind fixed on the immeasurable’. The 'Romantic / Objective' nature of such diagrammatic images was the subject of my PhD thesis, chapters of which are available for download from the research page of this website. References: 1) Judy Egerton [and Clifford Ellis], ‘JMWT PP’: A Selection of Drawings Made by Turner to Illustrate his Royal Academy Lectures as Professor of Perspective, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1980, p.1. 2) Mr Turner's lectures at the Royal Academy, The New Monthly Magazine, 1 February 1816, p.60. 3) Annals of the Fine Arts, vol.4, London 1820, p.98. 4) CP 4.8-11 5) Richard Redgrave, A Century of British Painters, 1866, p.95. For more information See: Andrea Fredericksen, ‘Royal Academy Perspective Lectures: Sketchbook, Diagrams and Related Material c.1809–28’, June 2004, revised by David Blayney Brown, January 2012, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/jmw-turner/royal-academy-perspective-lectures-sketchbook-diagrams-and-related-material-r1131857, accessed 18 March 2016. |

Dr. Michael WhittleBritish artist and Posts:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|