|

❉ Blog number 18 on diagrams in art and culture revisits an interview I made in 2013 with the artist Richard Talbot. Richard is a leading authority on perspective, and Head of Fine Art and Professor of Contemporary Drawing at Newcastle University in the UK.

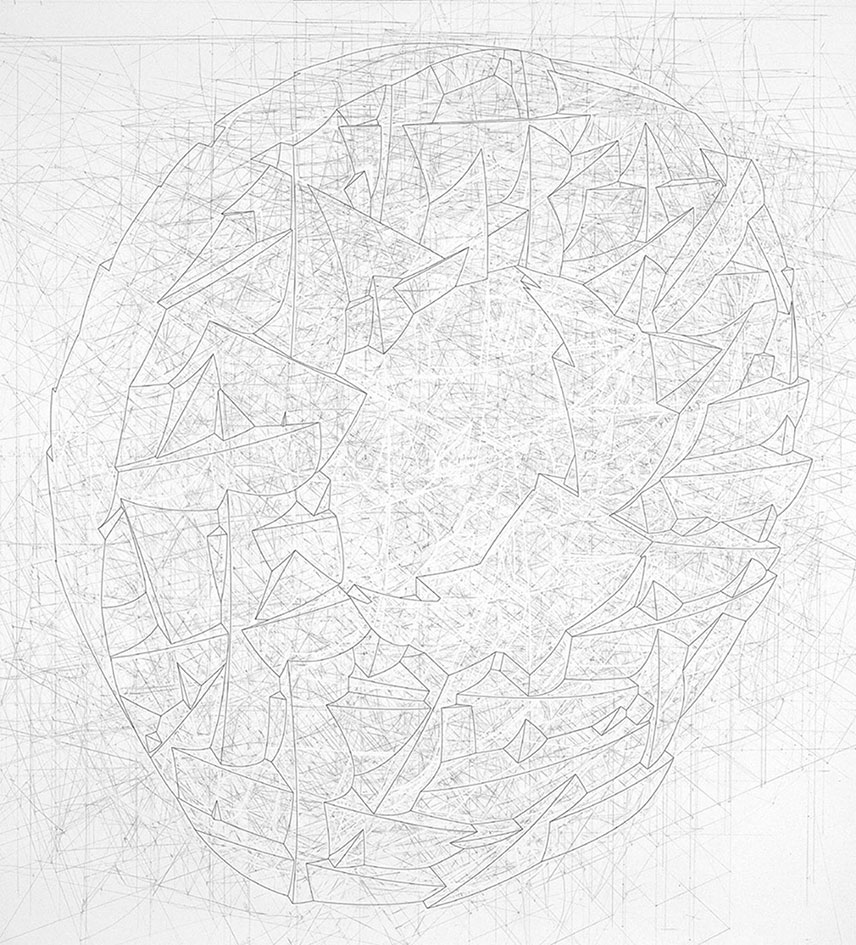

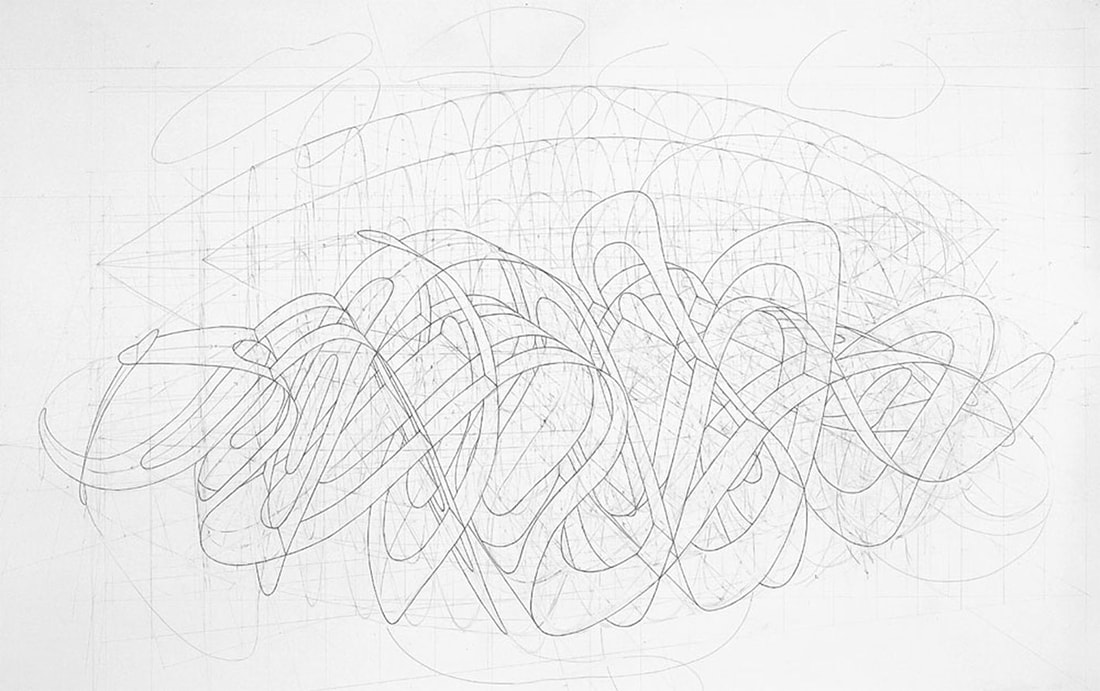

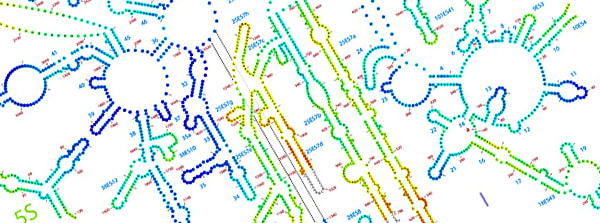

Figure 1: Richard Talbot, Random Moves, 1989, pencil and ink on paper, 120 x 120cm

The diagrammatic drawings of Richard Talbot present viewers with a palimpsest of their the own process of creation, or working-out. Each image sits embedded within a network of the construction lines and erasure marks from which it has arisen, and the artist himself suggests that this promotes the idea that the process of drawing itself can be considered the medium of his work, rather than the materials chosen to make the drawings (1).

I first discovered Richard's work in the book 'Writing on Drawing', a compilation of essays edited by Steve Garner, and published by Chicago University Press in 2013. (More information about the publication is available in a previous blog post: Diagrammatology: A reader.) Richard's contribution 'Drawing Connections', comprises chapter 3 of the book, and introduces his studio practice and academic research in to the theory, history and practice of perspective. As a second year PhD student in Kyoto I travelled to the UK at the end of the summer in 2013 as part of a research trip to interview artists and theoreticians working with diagrams. One of the highlights of the trip was the opportunity to talk with Richard in his beautiful studio and office in the distinctive, red-brick, double arches of Newcastle University's Gate Tower.

The Arches viewed from the Quadrangle, Newcastle University.

MW: You originally had studied Astronomy and Physics ?

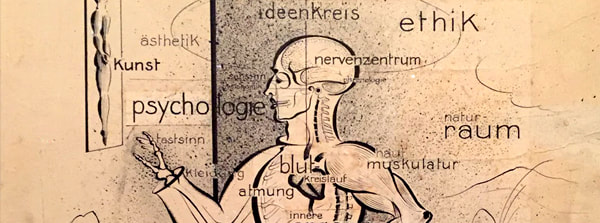

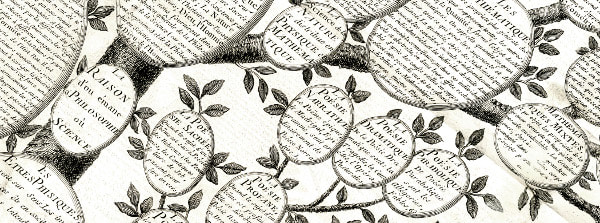

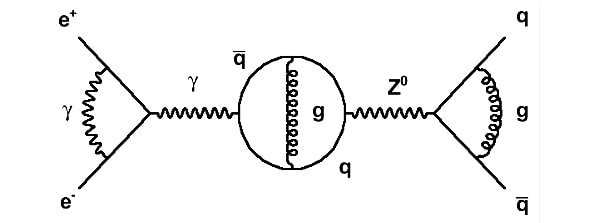

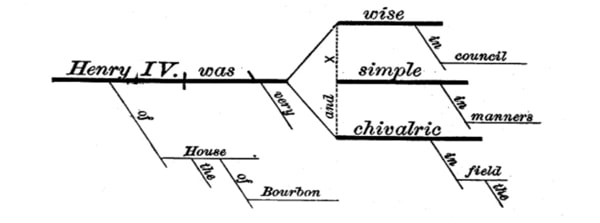

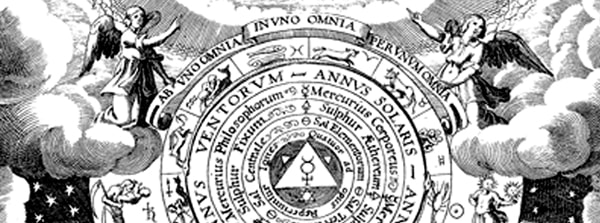

RT: I did, but realized early on that I had chosen the wrong subject. I noticed also that you had studied Biomedicine. MW: Yes, so I was immersed in diagrams, especially as I specialised in Biochemistry, which as a subject deals with diagrams on many levels. RT: Yes, when I was at school, all the chemistry diagrams and the glassware we used, I still find very exciting, it still gives me a buzz when I look at those diagrams. Also I suppose that Alchemical drawings which are in a sense diagrammatic, but which also refer to broader cultural aspects and spiritual things. But I think it is that combination of diagrammatic mixed with something else where things become very interesting. MW: Especially for the initiated few who can decode and read the Alchemical imagery and illustrations such as those in Michael Maier’s books. And you were also interested in optics and optical diagrams ?

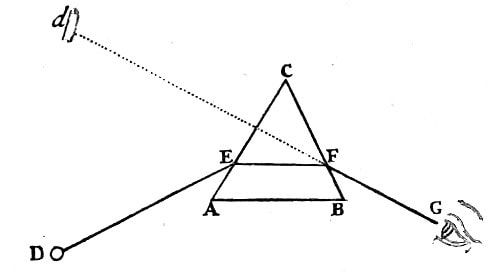

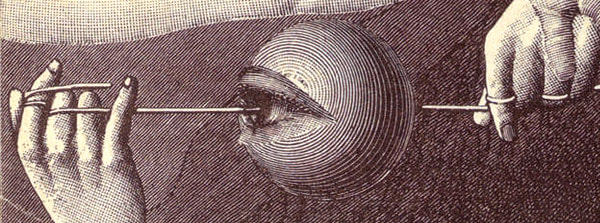

Figure 2: Ray diagram from 'OPTICKS: A treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and Colours of light', Sir Isaac Newton (forth edition, 1730, Available online here)

RT: Again, I always was - by the geometric diagrams of optics: the eye, mirrors, the idea of ‘looking through’, I was interested by that whole system; the picture of the eye, the rays coming in to the eye, or out of the eye. I find all of those things exciting, and I think that it’s because you’re almost standing outside of the system, and you can see what this system is.

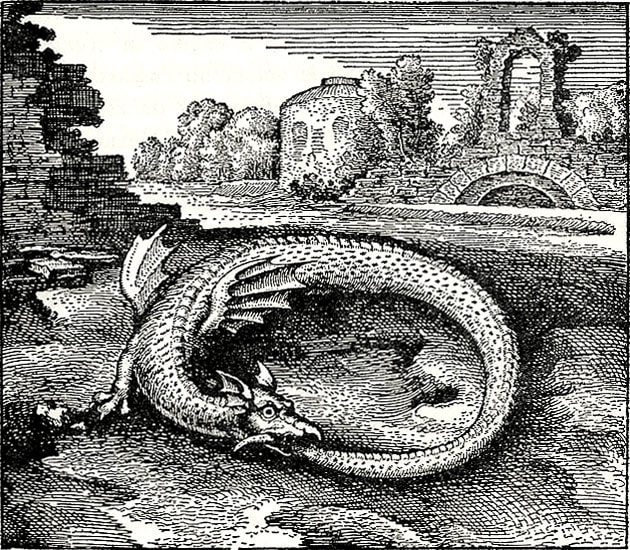

MW: That’s something I wanted to ask you about because you had mentioned that you were interested in landscapes, and the idea that maybe the drawings you make are detached, conceptual landscapes. I remember reading 'To the Lighthouse' by Virginia Woolf, and there’s a very short chapter in the middle of the book, which describes time passing in an empty room. But it does so from outside the book, from the detached perspective of an omnipotent narrator, an all seeing eye. I wondered if that was something you were interested in as an artist? RT: Yes, I think so. I suppose maybe it’s this kind of hyper-consciousness, just this thing, observing, and you just become very aware of time and space, and of yourself as a little entity within this. It’s almost as if time disappears. The other thing I remember reading a lot as a student was Nietzsche, and the image of time as a snake eating its tail. He called it ‘eternal recurrence’, where you’re trying to imagine that every moment could be relived exactly the same, so it kind of neutralizes time, because as animals we’re stuck with this as a problem and try to find strategies to overcome that sense of things in the future and things in the past.

Figure 3: Michael Maier, Ouroboros, Emblem 14, Atlanta Fugens, 1617.

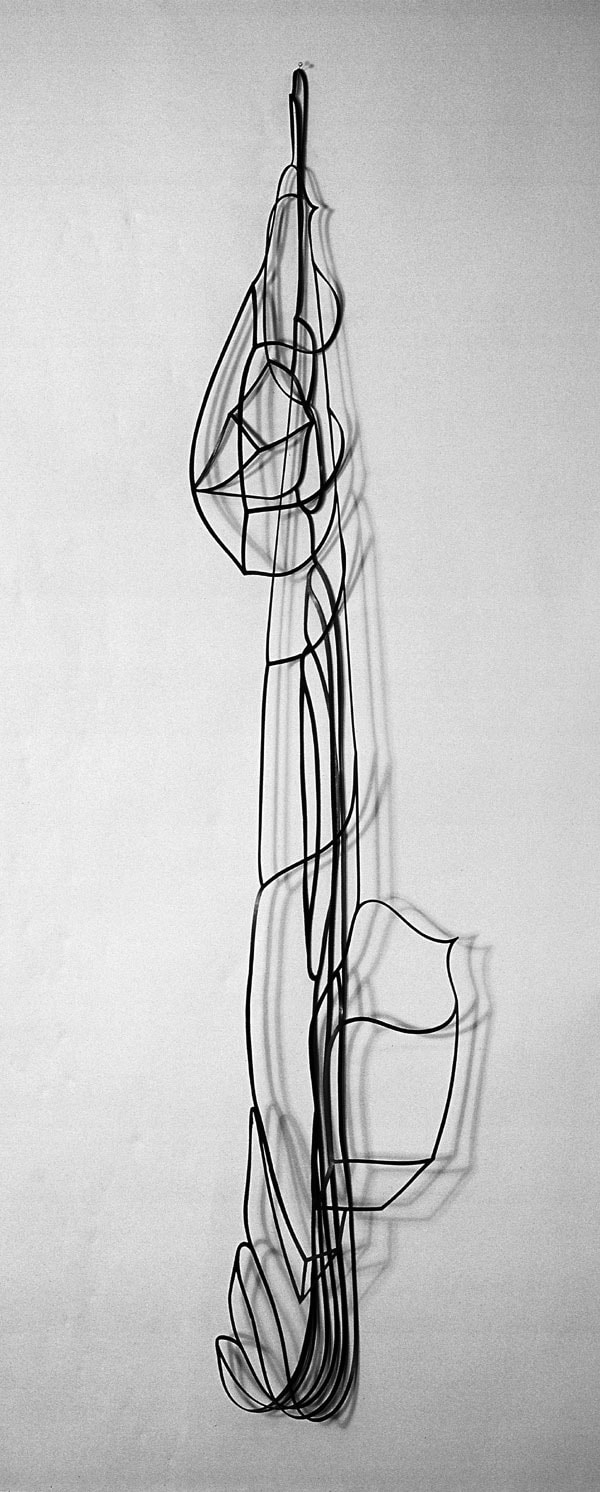

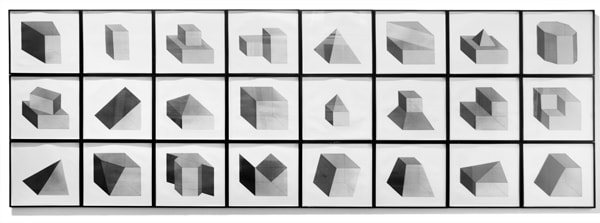

MW: I read that time was something that you would like to take out of your drawings, or perhaps avoid referencing in some way. Also, that you presented the objects in your drawings as Platonic forms, without any signs of wear and tear or reference to scale. RT: Yes, that’s right, I started off by making objects, but always found it really frustrating in terms of size, or what you make it with. But I suppose that a lot of the twentieth century was about that problem, about objects, and their separateness to us all. MW: Such as the use of Plinths to present work ? RT: Yes, for example Plinths. MW: So did you ever regard your sculptural works as models, as a way to perhaps overcome these issues ? RT: I suppose I did think of them as 3 dimensional diagrams, but then I suppose that made me unhappy about the materials they were made from. I always imagined whether perhaps it could be made out of perfect marble perhaps. MW: I started to consider making works from elemental materials, such as aluminium or carbon, just to try to deal with the problem of simplifying or neutralizing that issue of materiality. One of the 3 dimensional works that you made called ‘boat’ was made out of rubber wasn’t it ? Hanging as a collapsed frame on the wall, the skeletal form of a boat.

Figure 4: Richard Talbot, Boat, rubber, 180 x 30 x 10 cm

RT: Yes, it’s funny that that particular series of works didn’t end up going anywhere; I’m just trying to remember what the actual sequence was. I think sometime in the early eighties, I was put forward for a commission; it was one of those completely random invitations to do something. It was for the Savoy Hotel. It was one of those awkward things of, well, do you design sculpture, or do you use something you’ve already got? So I started playing around with drawings and making cutouts from drawings of things. I ended up with some large sheets of rubber and started cutting it out to see whether it was something I could use. I didn’t intend to end up with something which would hang on the wall, but I did that in the studio by putting it to one side, and it’s quite extraordinary how that works. So it was quite accidental, but was just the recognition of having taken it in to that different area that I didn’t have any control of, so it was quite accidental. It was all cut by hand, so it was a very crisp line cut with a scalpel. MW: About your working process, you wrote very beautifully about that initial process of orientation, the initial white sheet that you approach, and the infinite possibilities you’re faced with - setting up some kind of initial starting conditions. You used the analogy of the Gothic Cathedral with its ground plans, and then the more organic process of construction that follows that. There was also another article in the same book (Writing on Drawing: Essays on Drawing Practice and Research) by Terry Rosenberg about ideational drawing, a process of drawing which I though really suited your work very well. RT: Yes, I mean I must say that I haven’t read fully all of the articles in that book, but have skimmed through them. MW: There were a couple of essays that really stood out for me personally, yours and Terry Rosenberg’s. I enjoyed the way you talked about your use of perspective, not as a tool to create realistic drawings, but as a tool to allow you to use your intuition. RT: Well I think that also goes back to that idea of self-consciousness, sort of knowing that you’re this entity that looks at something from the outside. I used to play around with spatial perspectives, and then I thought that actually one way of neutralizing these issues was just to use it, just to actually use the system. So that to get over that whole issue of viewpoint, for example when you make a piece of sculpture, how do you look at it ? If there’s no best side as it were. So I thought, well if I just take it on full, this issue of perspective, and to absolutely use it as it was set up to use, then it falls by the way side, as an issue. MW: Turning the problem in to part of the solution? RT: I think it’s like sometimes in Mathematics, when a problem can’t be solved directly, they will call on a tool from other part of mathematics, and using that tool they can then move from one place to another. But in the end result, that tool disappears, it doesn’t ultimately play a part in the answer, but it has been a useful tool to get you from one place to another. MW: That reminds me of the role enzymes play in Biochemistry. They’re completely essential to facilitating the process, but don’t take part in a reaction in a way that they are altered themselves in the outcome. RT: Yes, that’s right, yes. So it is a kind of a vehicle, but then it’s using that perspective that makes me then question how it was originally used in the Renaissance, because when you’re actually working with it on the paper, there are so many interesting things actually going on that art historian looking in from the outside wouldn’t grasp. And it is to do with that idea of play, between the diagrammatic and the spatial element. Perspective isn’t all about creating a space, it is about the surface and how these things operate 2 dimensionally as well.

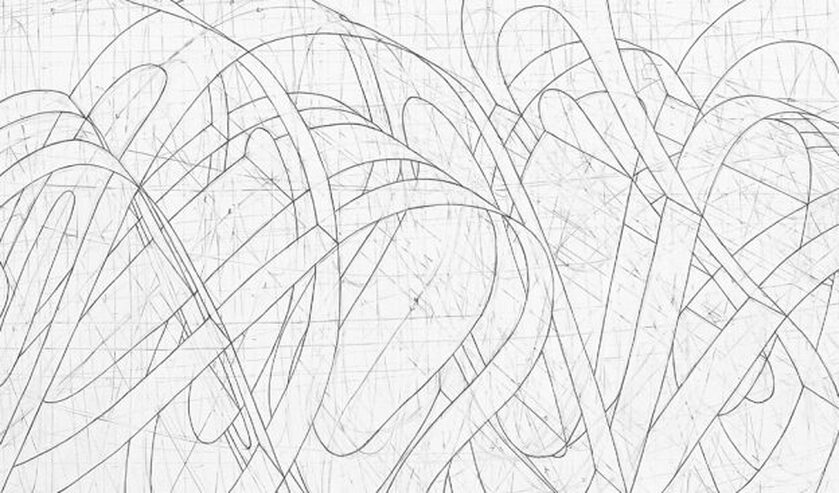

Figure 5, Richard Talbot, Missing the Target, 1989, pencil on paper, 140 x 80 cm

Figure 5, Missing the Target (Detail)

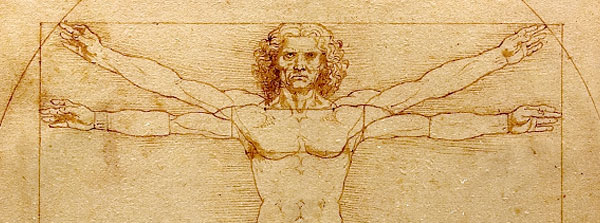

MW: I was very interested in the way you talked about the depth of space in your drawings, and not using deep space, but keeping things relatively shallow and immediate. RT: Yes, I think that this also relates to my sense of what these Renaissance artists were doing. The picture that is portrayed of perspective is all about getting everything in terms of the horizon. But I don’t actually think that’s it at all. You are really working in a really shallow space. All those Renaissance paintings are also working in a really shallow space, and I think when you’re actually constructing that on the paper, there’s a real, almost physical connection to the space. MW: I don’t normally use colour in my work, it’s actually something I avoid, and have for a long time. Then I came across a book by David Batchelor called Chromophobia. He was writing about colour and how it has been perceived as the additional, the exotic, the lipstick. Or at least that’s how it was regarded by artists and writers who saw it as extraneous. And so I’m interested to ask you how you deal with colour in your work. RT: Well I have to admit as to having always avoided it, as I’ve never understood it. It’s a complete mystery. If I was making a drawing, I can’t see any reason to use colour. But then equally I probably can’t see any reason not to use it. But then I would probably be thinking well, why do I ? But then I know with somebody like Michael Craig Martin, I suppose he’s somebody in the seventies who was producing very austere, paired down work, such as his linear drawings, which were initially all black and white. But then he probably just stopped worrying and started to use incredibly strong colours in his work. And now the colour is really significant to his work. But its interesting that Michael Craig Martin was taught by Joseph Albers. MW: That’s interesting, I didn’t know that. RT: Yes, at Yale. So he would have had a real grounding in colour, and it’s almost as if he, you know – 30 years later or whatever it was – just decided to start using these colours. It is odd how we set rules for ourselves and at the time we kind of need them, but occasionally we just think ‘drop them’, and stop worrying about them.

Figure 6, Richard, Glass, 1989, pencil on paper, 110 x 100 cm

MW: There were a number of times when looking at your works and reading what you wrote about them that reminded me of mathematics, and the idea of skeletonized forms. The idea of an equation, where the aim is to remove as much information as possible and leave only the knowledge - the process of essentializing something. Also the way that you talk about using intuition, and how intuition can be very immediate, or how it can require you to put the work away for many years. A slow boiler that you come back to much later. Is mathematics something you’re interested in? Or is it restricted to geometry, or patterns of thought? RT: Yes, I’m interested, not in the sense of reading books on mathematics, but when I’m near mathematicians and they talk about what they are doing, I do feel an affinity with what they are doing, and I suppose that with my drawings, they become very complex, but I do have that hankering after something really, really simple. I do have this idea that one day I’ll just be able to draw a line, and that that will be the finish! And in a way I suppose you do occasionally see it in some art works – and think that that is just an extraordinary piece of drawing, but then that in a way embodies everything they’ve ever done – 40 years later they’ve managed to make this extraordinary thing ! MW: Richard Dawkins wrote a while ago about the idea of a conceptual space containing all possible genetic variations, a kind of hyper-space of all possible genetic forms, and I was always fascinated by that idea. I think that also Douglas Hofsteader in Goedel Escher Bach, described the idea that Bach, in composing, had the ability to look over all the millions, well almost infinite combinations of musical notes, and was able to see patterns, islands or constellations of musical forms. And I wondered if that idea was perhaps something you were interested in. A vaguely discernible, fuzzy possibility of the form you’re searching for, and how this idea relates to diagrammatic forms.

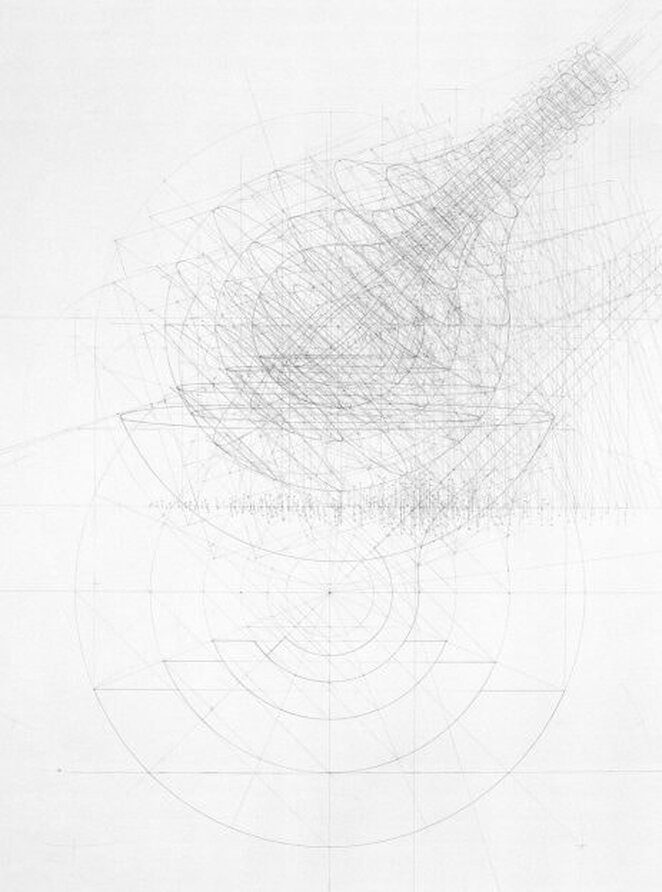

Figure 7: Richard Talbot: Step up, step down, pencil on paper, 120 x 120 cm

RT: Yes, I think that is definitely true, and I suppose that one of the things I am aware of is that in some ways, the drawings all start from the same point. That blank paper, that orientation. MW: The tabula-rasa ? RT: Absolutely, and you know that it could go in a completely infinite number of directions, and yet there is a sense that there is some solution there - that you setting things up. It becomes very obvious sometimes. I wouldn’t compare myself to Bach, but I can see that way of thinking - that there is an infinite number of possibilities, but you alight on a particular form that is true for you in one sense or another. It’s hard to really articulate that process.

MW: How would you describe the relationship between the forms in your drawings and the marks which make up the background from which the image appears ?

RT: I think when I first started using perspective I was still in that mindset of drawing objects as things in space, but then quite quickly I became aware of how potent the workings-out - you know, the plans, the elevations and so on - how potent they were and how they were working with the kind of forms which were being described. It was also in trying to pin things down, I became aware of the balance between leaving things open ended and tying something down and saying ‘this is that form’. It was that form, but not in such a positive or fixed way. I stopped using ink on the drawings. I was using ink to go around the forms I was building, but that stopped. And so I started getting a much more subtle interplay between the workings out, and those workings out would be the plans, and elevations, and a myriad of other kind of connections which were being built, a kind of scaffolding. MW: And you saw inking in as a kind of finishing process ? RT: I did. You know you suddenly think that it has in a way killed off the drawings. Not inking became a way to leave the drawing as an open-ended thing. Perhaps when a work is too ‘closed down’ it can end up being very uninteresting. For example Raphael. I’ve never enjoyed looking at Raphael’s paintings because they seem so overly fixed, whereas, Piero de la Francesca’s paintings seem almost as if they are propositions.

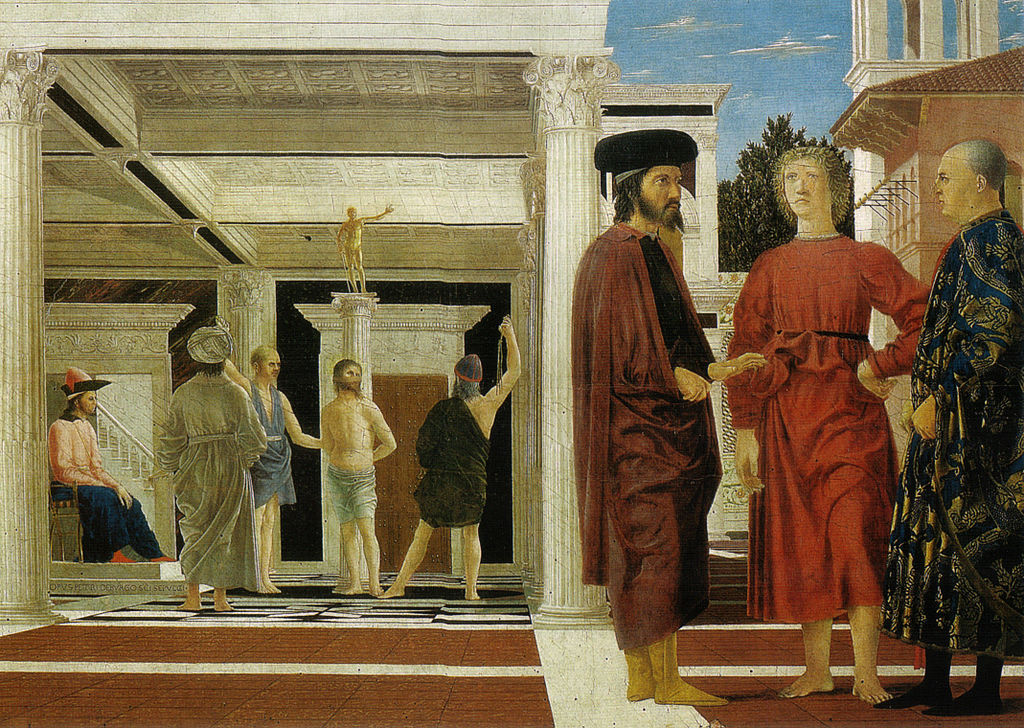

Figure 8: Piero della Francesca, Flagellation of Christ, c.1468-70,

Oil and tempera on panel, 58.4 x 81.5 cm

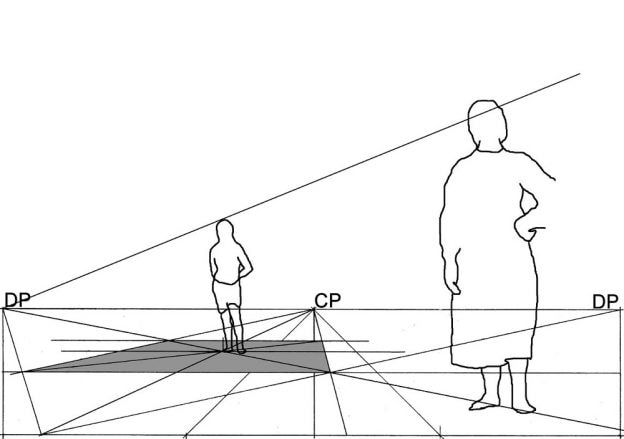

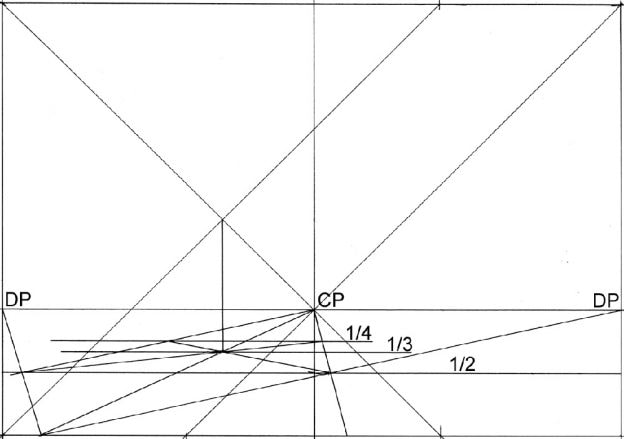

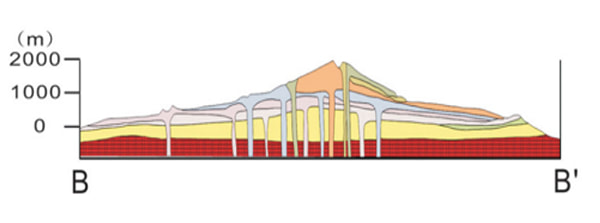

Figures 9a,b, Diagrammatic Study of Piero della Francesca:

The Flagellation of Christ (outline and outline proportions) Courtesy of Richard Talbot. MW: Very early on in coming up with the questions that I wanted to ask in my PhD, I pretty much hit the same problem you did in realizing that I had always studied sculpture, but always made drawings. And I thought of the drawings as sculptural drawings and, luckily for me, my teachers at the time thought the same. So I had to decide whether to investigate the relationship between 2D and 3D diagrams - and thus include sculpture, or the way in which artists use diagrammatic image making to a romantic end, a subjective end; the way in which Marcel Duchamp played subject against object and also struggled with the issues of dimensionality. Where do you stand in terms of subject and object ? RT: Yes, well I don’t think I would come down either way, because I don’t think that coming down on either side actually gets you anywhere. I suppose that in my student days, this dilemma about the objective and subjective was helped by there being, at Goldsmiths - which was something which was great about Goldsmiths at that time - was that there was a huge range of practice within the staff. So you did have conversations with people who were systems thinkers, right through to people who were watercolour, or landscape painters. People weren’t trying to ram the stuff down your throat; you were just having these interesting conversations, and then weighing it up about your own situation. Thinking about what you were doing, what you thought you were trying to do, what you were actually doing ! You know, all those worries you have about, you know, ‘is it art ?’ I found myself really being able to make work when I stopped worrying about what side of the fence I was on, and finding a way of working where I felt as if I wasn’t having to choose one way or the other. But both sides of me could be involved in that hankering after perfection. It’s a case of playing these things off against each other. I distinctly remember that when I did my MA at Chelsea, the external assessor we had was Paul Neagu, I think he’s dead now, but he was very well known. He was one of the artists who Richard Demarco brought to this country, alongside such artists as Joseph Beuys. Anyway I remember that the work I’d made at Chelsea had become really quite austere, and extremely minimal, and he said… ‘don’t forget the other side of yourself’, and I realized exactly what it was he meant. That we can easily kind of forget. But then I think that also we need those extremes sometimes, to realize something. We need to go beyond in order to know where the edge was. It’s only when you fall over the edge that your realize there was one ! MW: So there is actually nothing within your body of work that you see as a mathematical proof, some foundation to build upon ? RT: No, I would certainly never say that there is anything that I’m demonstrating that is mathematical, no. I could say that when I was at Goldsmiths, I was taught by people who were involved in systems, and there were several people I knew, for example Malcolm Hughes working at the Slade, who had students working with experimental systems, building computers to generate paintings and so on; and I always felt that there was a problem in that they knew the kind of thing they were aiming for, and that it just seemed as if, well, you could make that painting without that system. It was almost as if they were using that system as almost a ‘get out’. The paintings would always end up looking like lots of other abstract constructive paintings that weren’t made with a system, that were just made purely intuitively. And so I have a distrust of the idea of a system, and I think that that system is always, ultimately being driven by you.

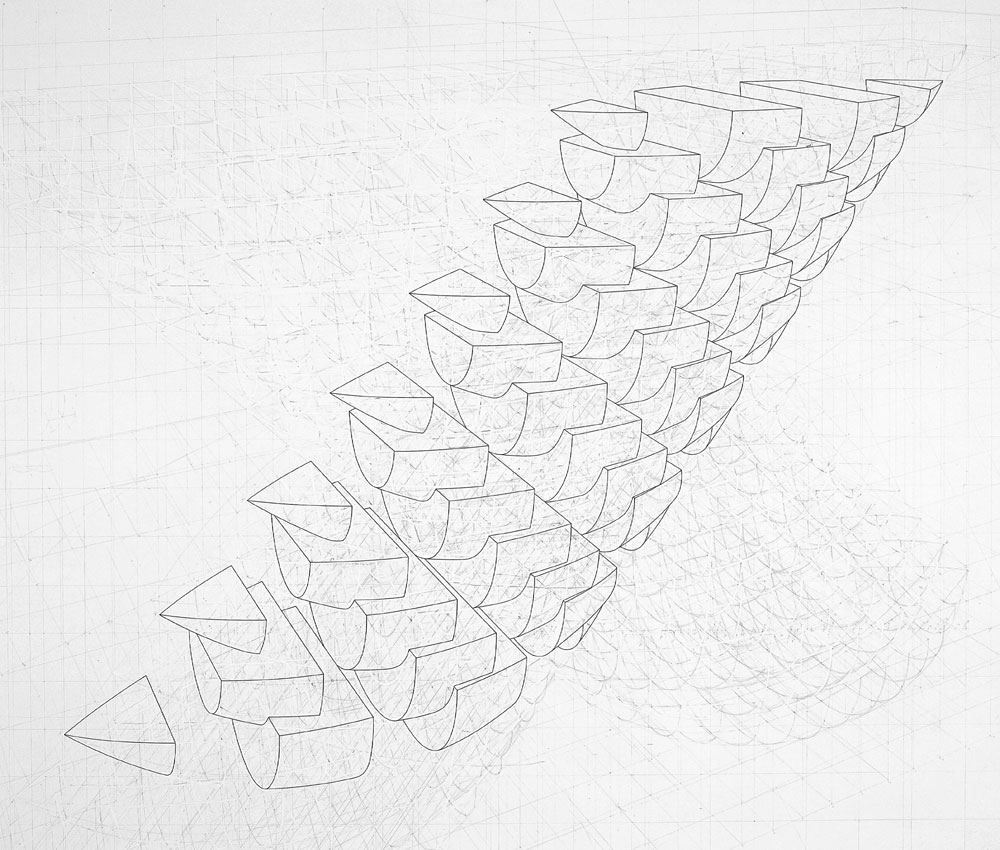

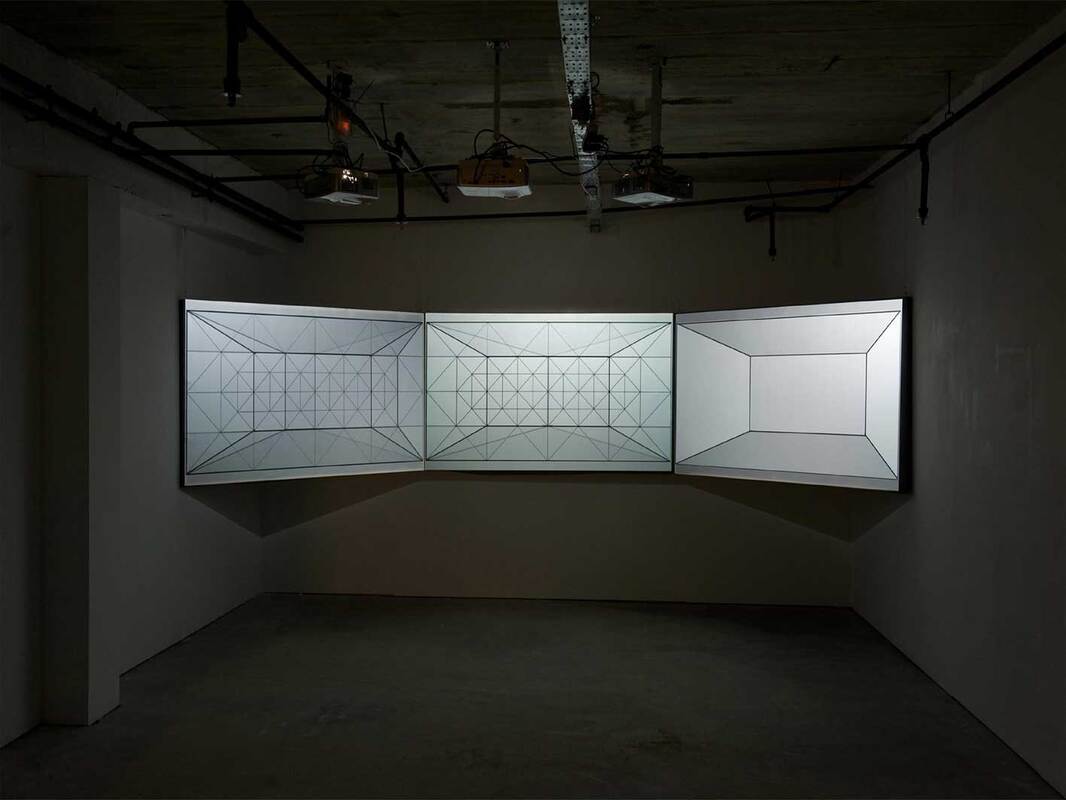

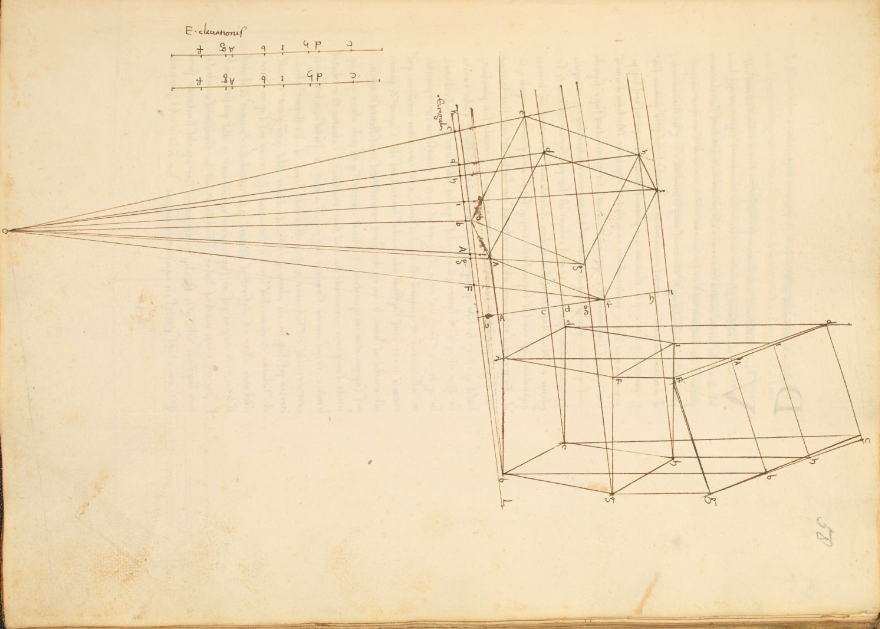

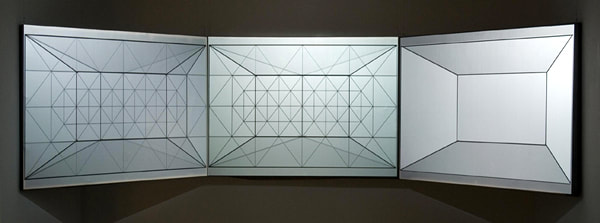

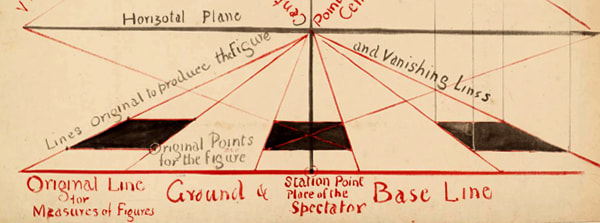

MW: What are you working on at the moment ? RT: Well apart form being heavily tied up in administration, I’ve finished some drawings and I’ve also been playing with film and video, which I can show you if you want. It’s very long drawing, based on a system in a sense, and was a definite play on the standard idea of a single viewer’s perspective. They start with a really basic perspective grid, a ‘unit’, drawn in such a way that I can simply add these units together and extend the space in any direction. Strangely, it adds the possibility of time, in that your eye can travel along the drawing and the space continues always to make sense. The video is another simple grid that is constantly shifting from the 2 dimensional surface in to the 3 dimensional image. Originally I had intended it to be projected on to a screen, but then I had the chance to project it in one of the large spaces downstairs, and the results were quite extraordinary - because it did actually become part of the space, which wasn’t fully intentional, but those were the results. The question of the artist’s intention is also an interesting problem I think within the history of perspective; the well-known analyses of key renaissance paintings demonstrate that the spaces in the paintings are sometimes not quite what they seem to be. There is often some uncertainty, yet it is usually thought that perspective is fixed - that it's an unambiguous and rational thing.

Figure 10: Richard Talbot, All depth, no substance, 2013, Installation view

MW: Watching the video feels like a trying to solve a puzzle in perspective, there are moments when the lines are like a 2 dimensional pattern of shifting compositions, and then suddenly something in the visual cortex takes over and there’s the impression of instant depth from those very same lines. It reminds me of watching animations of higher dimensional cubes rotating. You think you have understood what is happening and there’s a sudden unexpected shift, you have to grapple with different kinds of depths. RT: Well - I don’t know - It’s to do with my intention, I’m not settling down to produce something which has a specific result. I know they do result in that, but I’m not setting out to do that. I am showing this work – I’ve never tried it before. I hope it works… It’s actually going to be projected on to three screens, the same image, butted up against itself, but slightly out of synch. So the whole thing will be ‘shifting’, so that a more complex thing will be going on. I have no idea what it will look like – it might just look awful, but then I’m trying it – for this show. Grid from Richard Talbot on Vimeo.

Richard Talbot's diagrammatic drawings are further discussed in chapter 3.5 of my PhD thesis, which is available to down load here.

Richard's academic studies in to the origins of linear perspective can be downloaded by clicking on the following link:

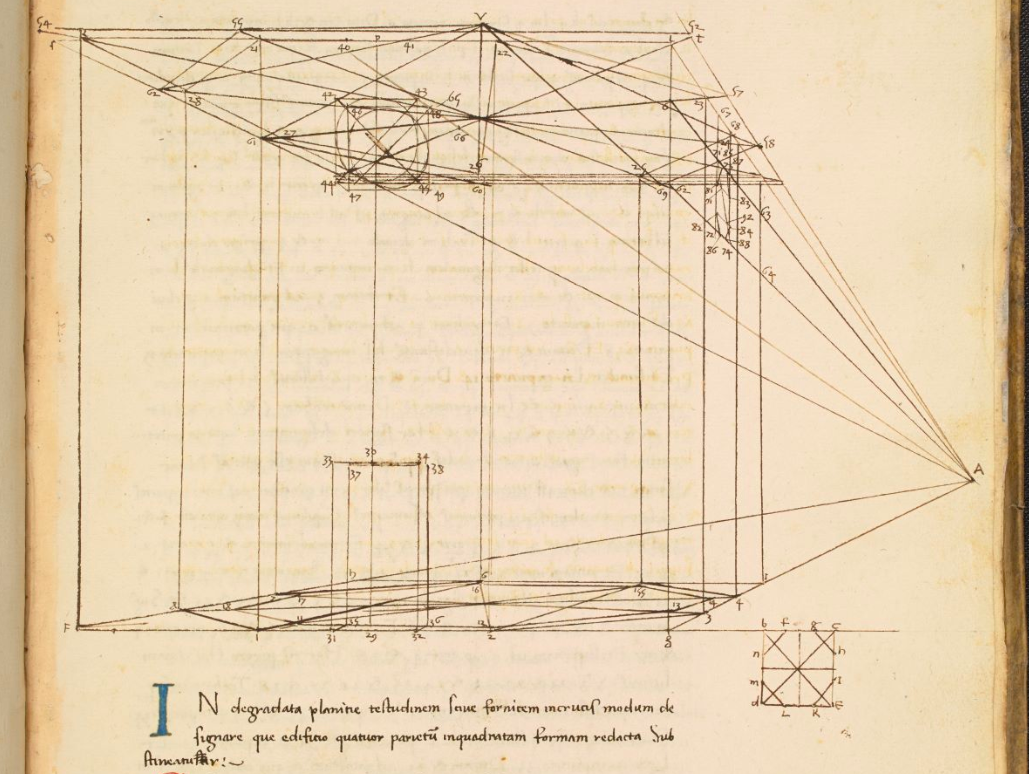

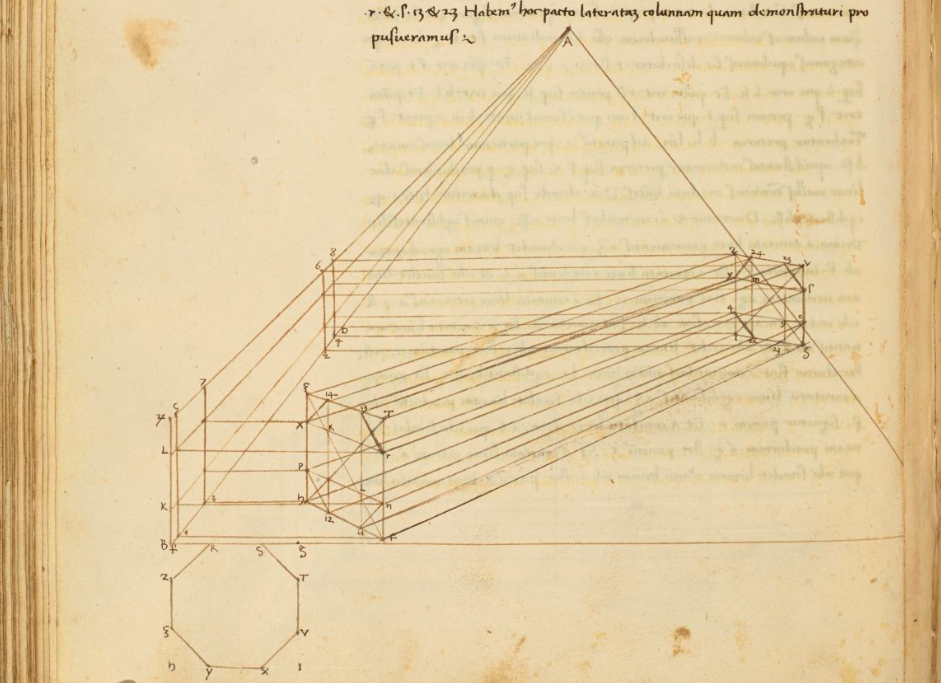

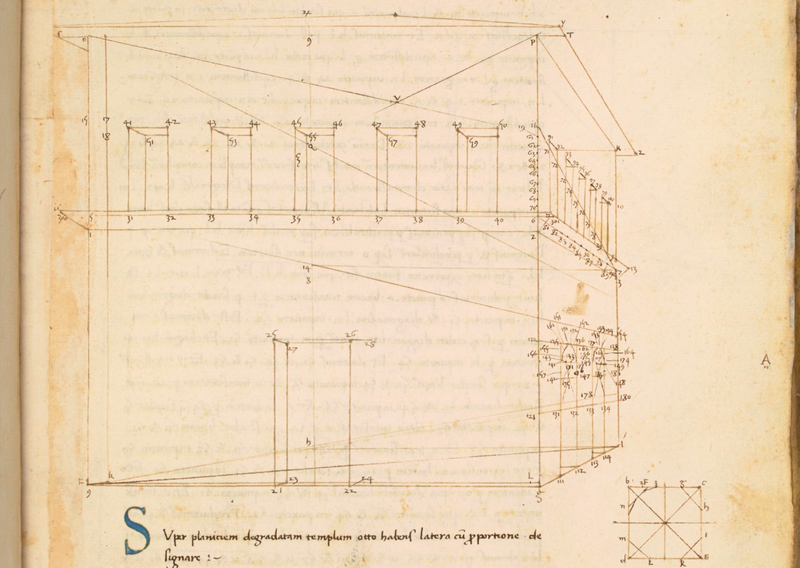

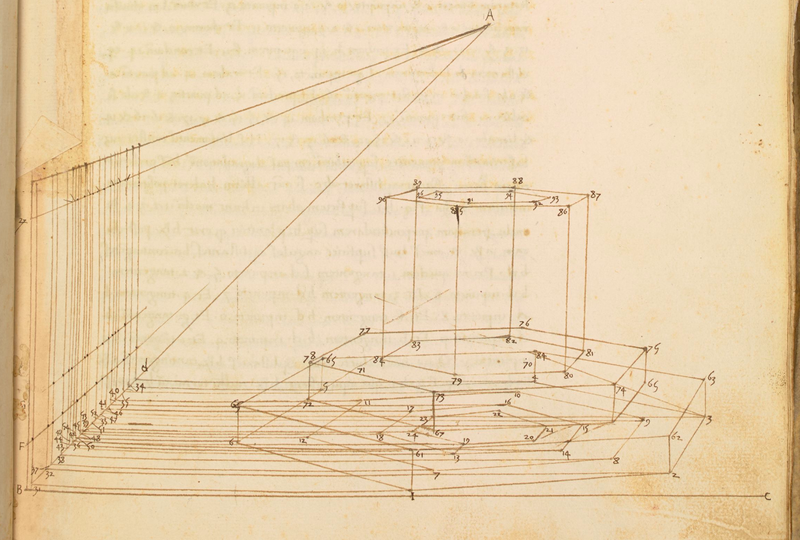

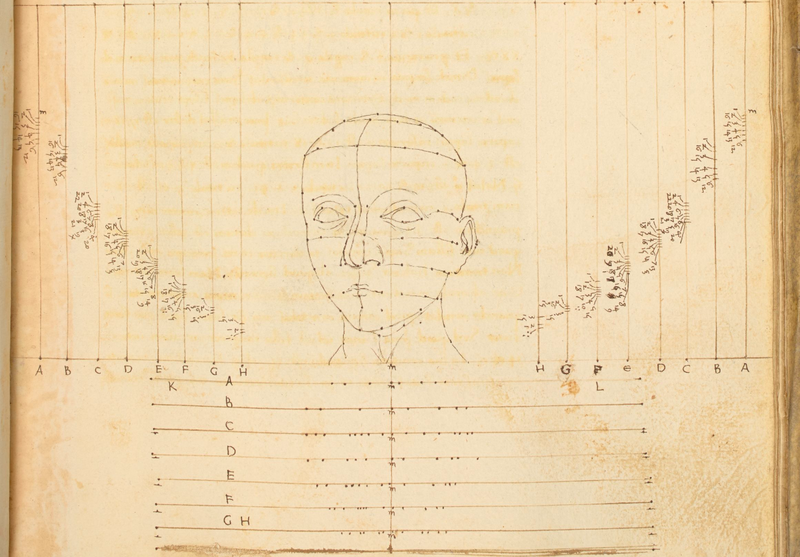

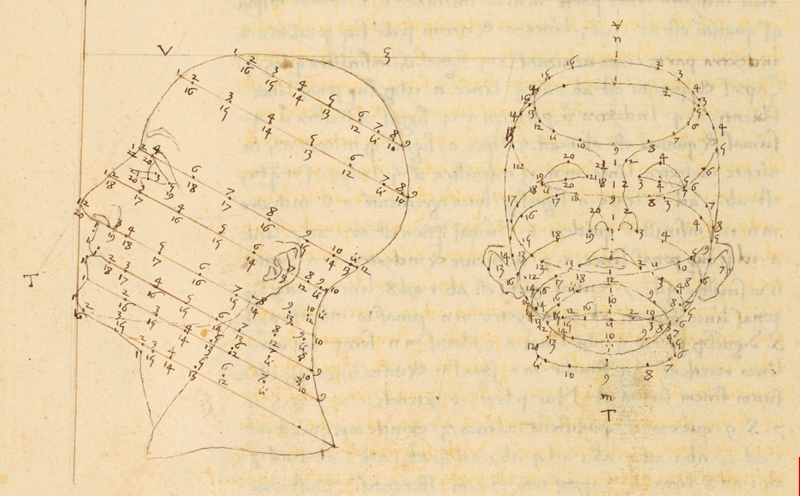

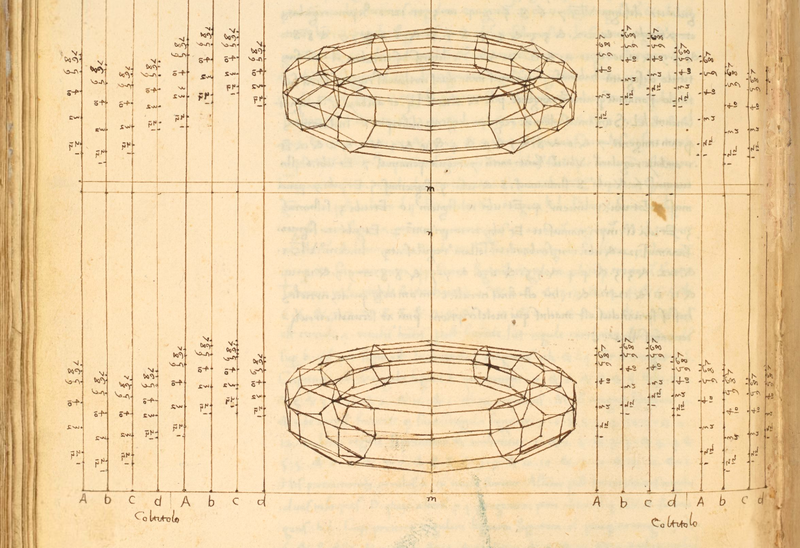

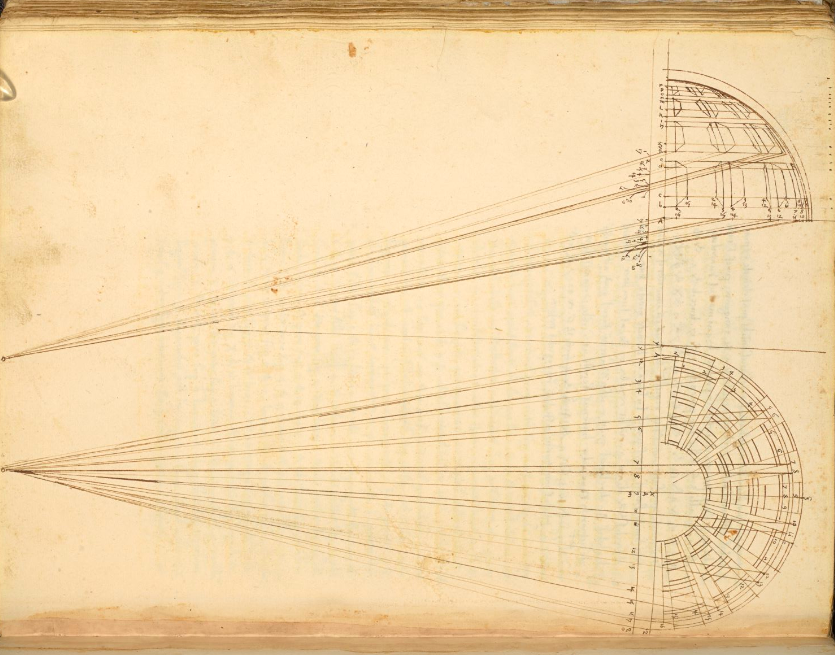

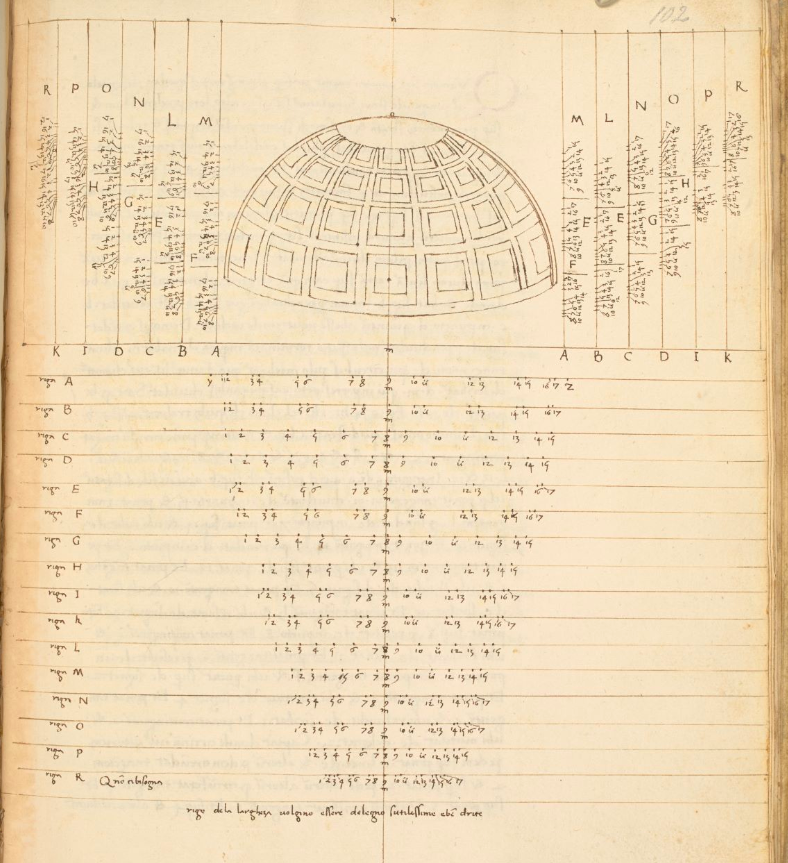

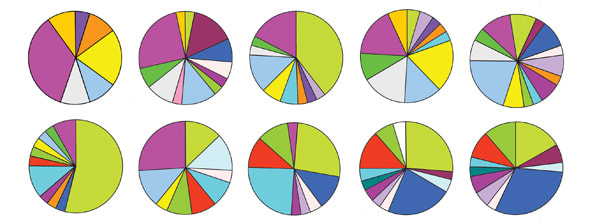

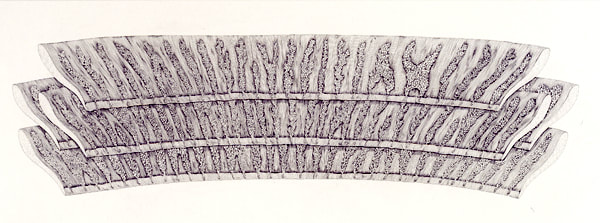

Finally, below are a series of Piero della Francesca's own diagrammatic studies from his book 'De prospectiva pingendi: a treatise on perspective' c 1470 - 1492. The treatise, divided into three books, provides detailed, mathematical instructions, illustrated with numerous diagrams, for creating realistic perspective in illustrations. It was widely known among artists (such as Albrecht Dürer), but also in an academic milieu, where the copies of the Latin translation are thought to have circulated. The book is available to view online at the British Library here.

References:

1) Talbot,R. (2008) Drawings Connections, In: Writing on Drawing: Essays on drawing practice and research (2008) Intellect Books, UK: Bristol, p.55. 2) Hughes, R. 1980, The Shock of the New, London: Penguin Random House Company, p.17.

0 Comments

|

Dr. Michael WhittleBritish artist and Posts:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

|||||||||