|

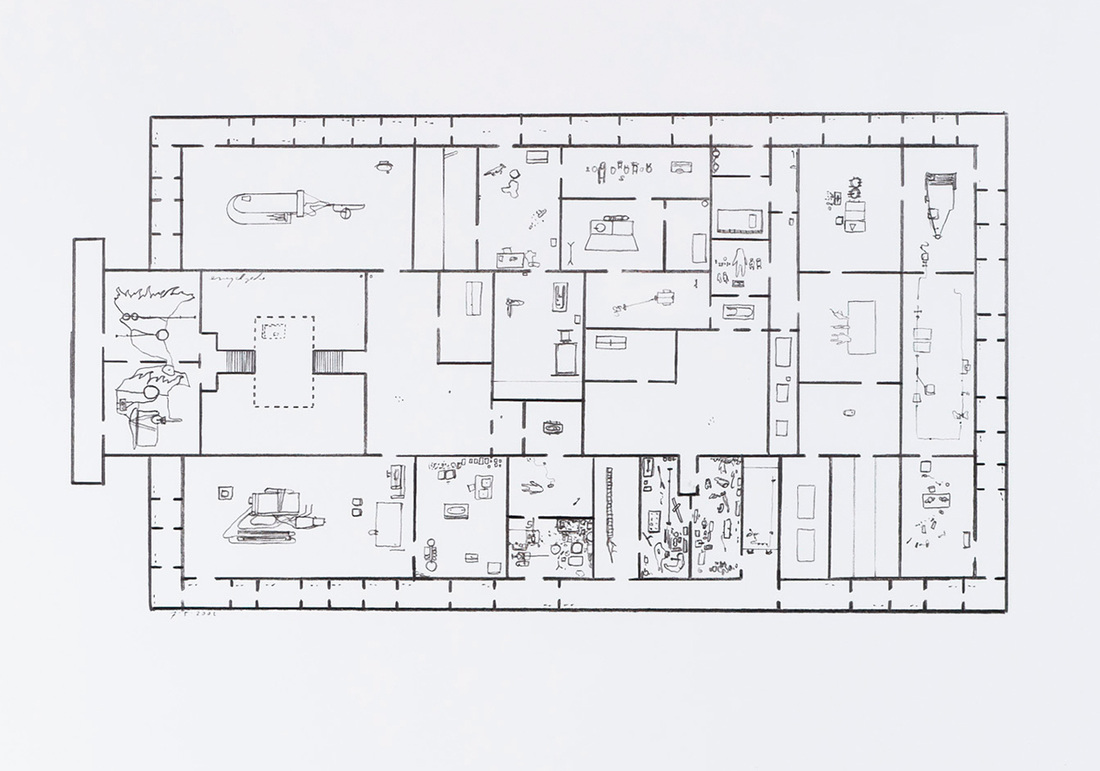

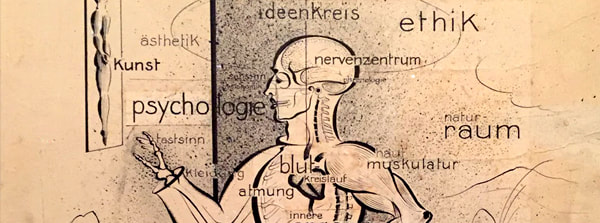

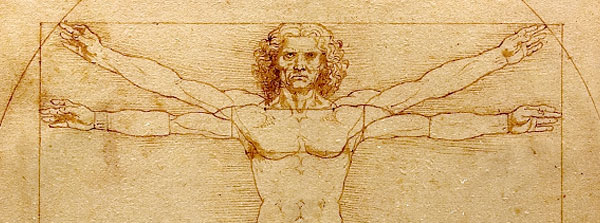

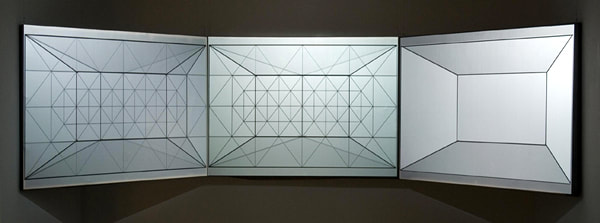

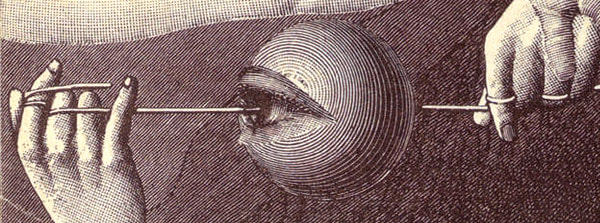

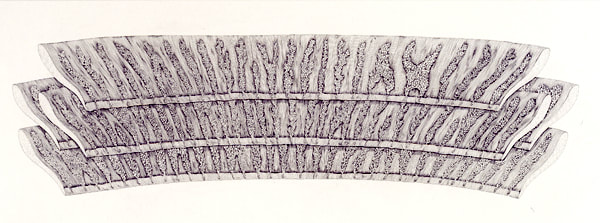

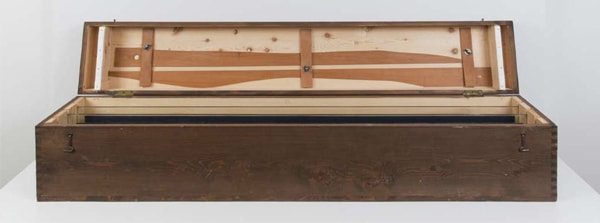

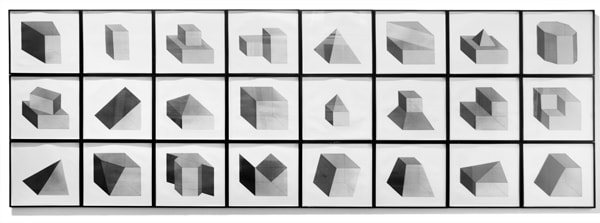

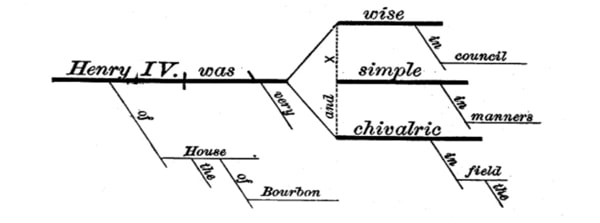

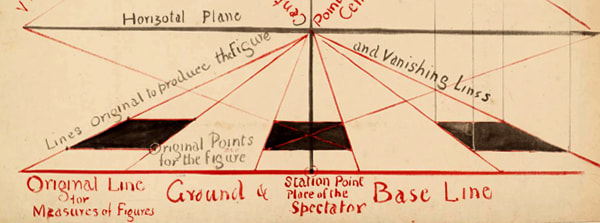

❉ This is the third in a series of blogs that discuss diagrams in the arts and sciences. I recently completed my PhD on this subject at Kyoto city University of the Arts, Japan's oldest Art School. Feel free to leave comments or to contact me directly if you'd like any more information on life as an artist in Japan, what a PhD in Fine Art involves, applying for the Japanese Government Monbusho Scholarship program (MEXT), or to talk about diagrams and diagrammatic art in general. Figure 1: Mark Manders, view of artist's studio with works in progress The Dutch Artist Mark Manders describes himself as “a human being who unfolds into a horrifying amount of language and materials by means of very precise conceptual constructions”. (1) Manders entered the world of fine art as a writer and text still plays an important role in giving key insights in to his practice. However unlike the artistic self portraits of James Joyce in prose, or Dylan Thomas in poetry, Manders' self portrait is architectural. Since 1986, Manders has been constructing what he calls his 'self-portrait as a building', and uses this conceptual framework to represent the fictional artist 'Mark Manders', a distinct alter-ego that he describes as a “neurotic, sensitive individual who can only exist in an artificial world.” (2) The Diagrammatic format is immediately apparent in Manders' projects as the means by which he marshals the "horrifying amounts of language and materials" that his mind is capable of producing. Diagrams provide method to his madness and imbue his art works with an air of precision, authority and logical rigor, even if we can only guess at their exact function. Figure 2: Mark Manders, Finished Sentence, 1998-2006, iron, ceramic, teabags, offset print on paper, 336 x 185 x 85 cm Manders' self portraits incorporate the diagrammatic format on three distinct levels: as an aesthetic, as a creative tool and as a means of organising and predicting the ways in which viewers will experience his art works as they pass through his installations. Aesthetically, many of the sculptures are formal constructs presented on table tops and in vitrines, resembling scientific models or experiments left unattended. Stephen Berg described these machines and factory-like constructions as “laboratory constellations for uncertainty and unknowable discoveries, production plants for dissident thoughts, transmitters for contacting the fictional.” (3) The floor plans and delicate pencil drawings show Manders' use of the diagram as a powerful visual and conceptual tool for creation and organisation, whilst the architectural nature of his exhibition installations guide viewers through carefully prearranged objects in a series of constructed environments, which the artist refers to as “memory spaces”. (4) Figure 3: Mark Manders, Drawing with Shoe Movement / Floor Plans from Self-Portrait as a Building, 2002, Pencil on paper Manders artistic practice is what I refer to as "Romantic-Objective", combining his own highly subjective and existential self-expression with an objective and analytical approach to phenomena mirroring that of science. Writing about his sculpture "Shadow Study (2)", Manders describes the thought processes that underly his choice of objects for the sculpture, and in doing so reveals it to be part exercise in 'material culture' (a kind of ethnography of objects) and part day dream. The visual language however is distinctively diagrammatic, and reminiscent of a highly reduced scientific demonstration or model. " If you think about the evolution of cups, it’s just a beautiful evolution. The first cups were human hands: folded together, they took the water out of the river. The next cups were made from things like hollowed pieces of wood or folded leaves, and so on. The last beautiful moment in the history of the cup was when it got a handle. After that, nothing really interesting happened with cups, just small variations, mainly ornamental. Many generations worked on it, and now you can say that the cup is finished in terms of evolution. A few times a day there is a cup very close to my upper leg bone, and I slowly discovered that if you turn an empty cup upside down there is a shadow falling out of the cup, falling upon my leg. I wanted to keep this shadow, have it and own it, so I turned it into an image. " (5) Figure 4: Mark Manders, Shadow Study (2) 2010, Metal, porcelain, painted epoxy, and wood / 151 x 65 x 65 cm "Shadow study (2)" subtly references the transparency of bone china, sunlight and shade, and creates a three part visual haiku of upturned cup and the 'pouring of shadow' upon the thigh bone, amplified by the pyramidal structure of the support suggestive of the conical rays of the sun. Mander's heightened awareness of the details of everyday life and the inherent paradox of both their importance and insignificance brings to mind a seemingly timeless quote, often mistakenly attributed to such greats as W.B. Yeats and Bertrand Russell: " The Universe is full of magic things, patiently waiting for our senses to grow sharper. " (6) In the case of Romantically Objective Art, that heightened awareness and sharpness of focus is due in a large part to the use of the diagrammatic format, in all its guises. Figure 5: Mark Manders, Shadow Study (2) 2010, Metal, porcelain, painted epoxy, and wood / 151 x 65 x 65 cm References: 1) Manders, M. (2010) Parallel Occurrences / Documented Assignments. Aspen Museum of Art, Aspen Art Museum and The Hammer Museum. p.11 2) van Adrichem, J., Bouwhuis J., Dölle M. (2002) Sculpture in Rotterdam, 010 Publishers, p. 60. 3) Berg, S. (2007) Like the night creeping into a shoe. In: In the Absence of Mark Manders. Berg. S. (Ed.) Hatje Cantz. p. 14. 4) Manders, M. (2003) Quoted in: Koplos J. Mark Manders at Greene Naftali - New York, Art in America, April 2003. 5) Manders, M. http://www.markmanders.org/works-a/shadow-study-2/2/ 6) Eden Phillpotts, 1991, A shadow Passes. [OXEP] 2004, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [Online], Entry: Eden Phillpotts (1862–1960) by Thomas Moult, rev. James Y. Dayananda, Oxford University Press. More information can be found at: http://www.markmanders.org/

2 Comments

|

Dr. Michael WhittleBritish artist and Posts:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|