|

❉ This is the second in a series of blogs that discuss diagrams in the arts and sciences. I recently completed my PhD on this subject at Kyoto city University of the Arts, Japan's oldest Art School. Feel free to leave comments or to contact me directly if you'd like any more information on life as an artist in Japan, what a PhD in Fine Art involves, applying for the Japanese Government Monbusho Scholarship program (MEXT), or to talk about diagrams and diagrammatic art in general.

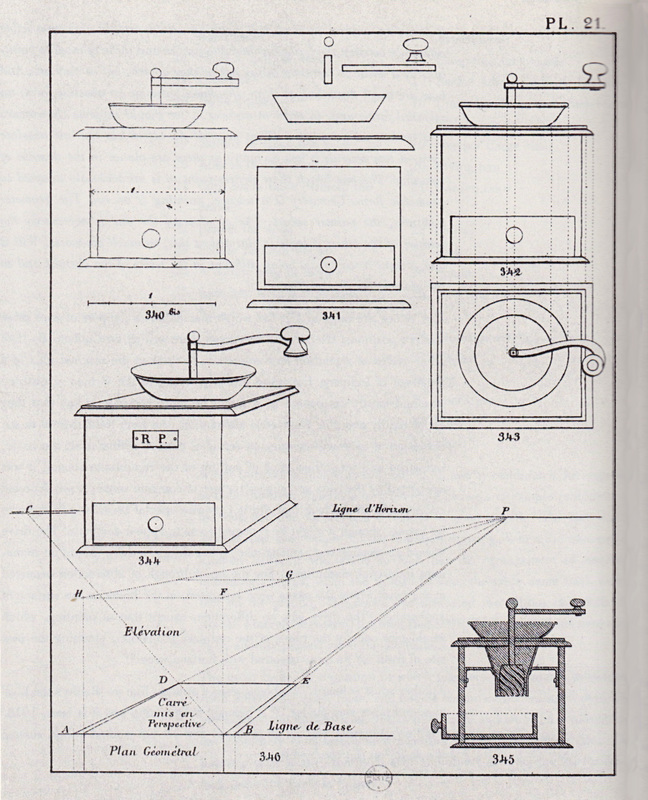

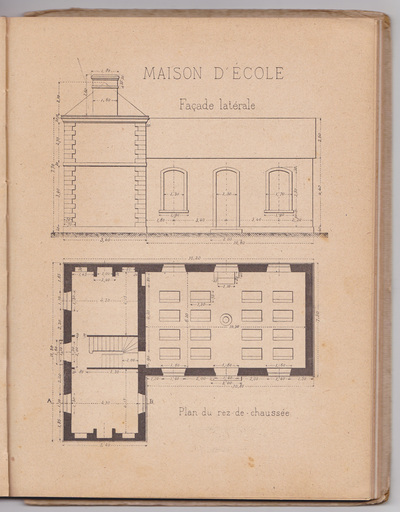

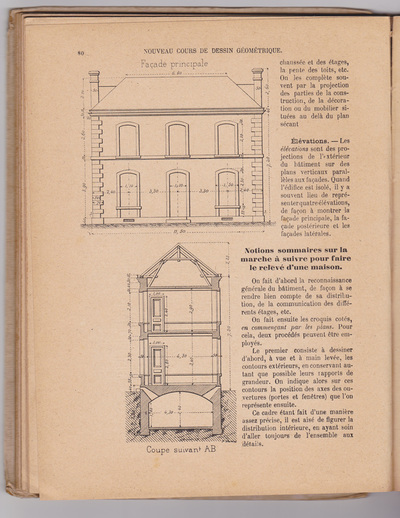

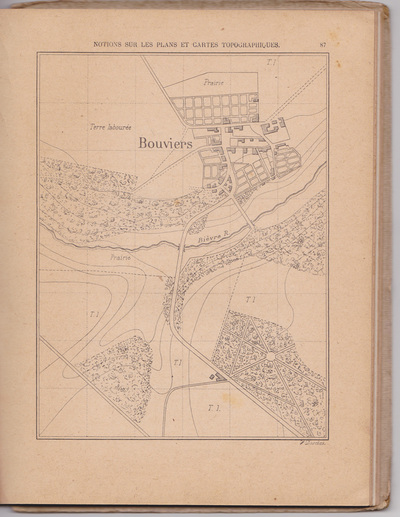

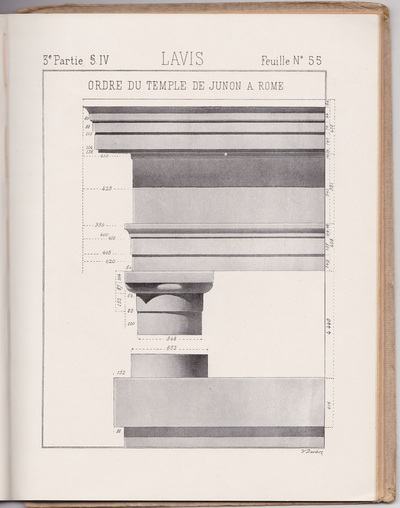

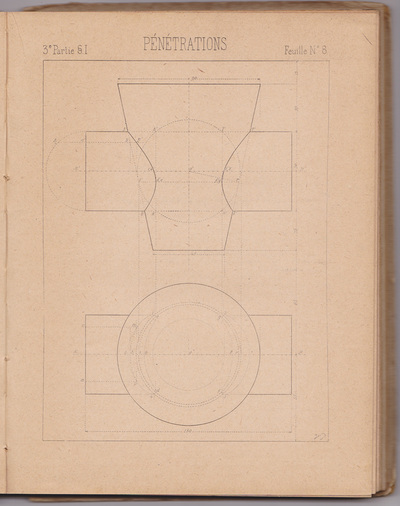

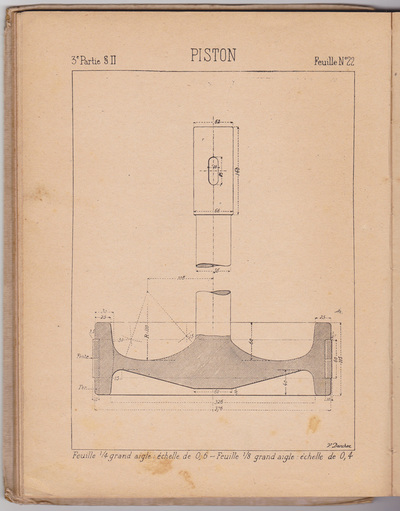

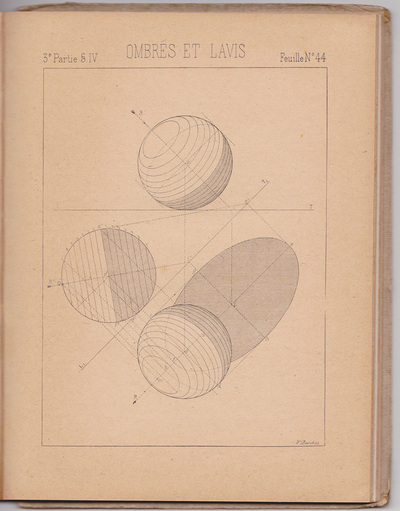

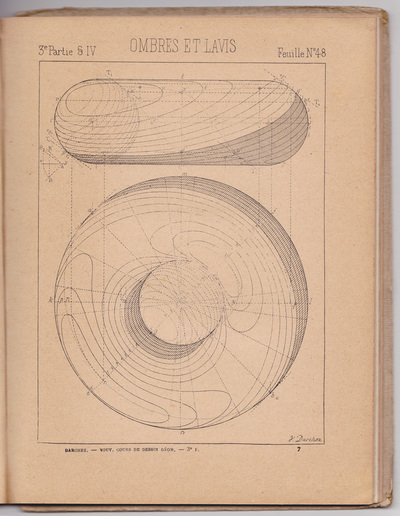

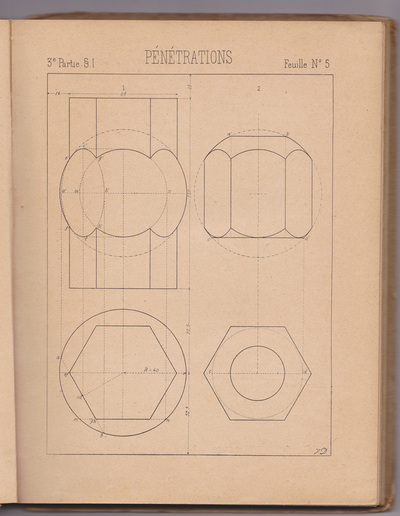

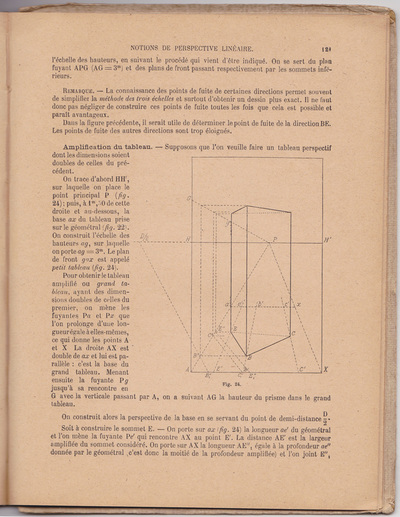

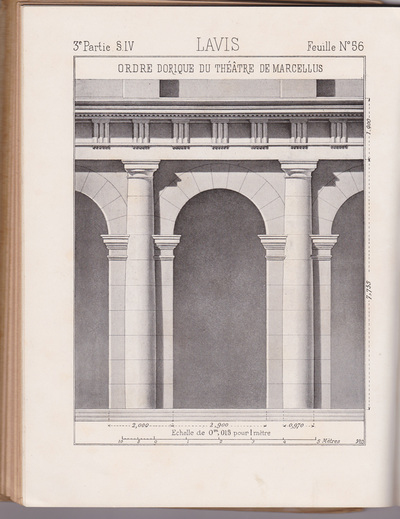

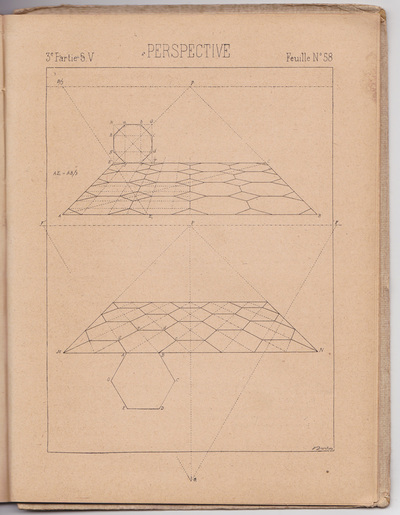

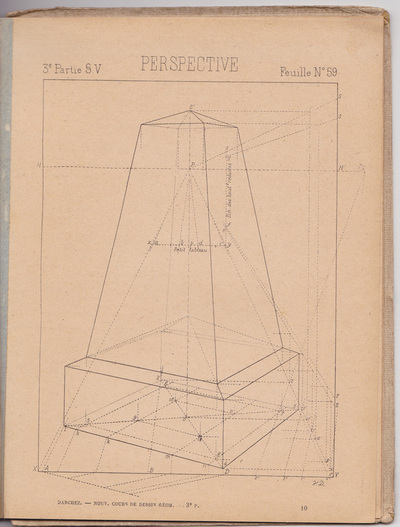

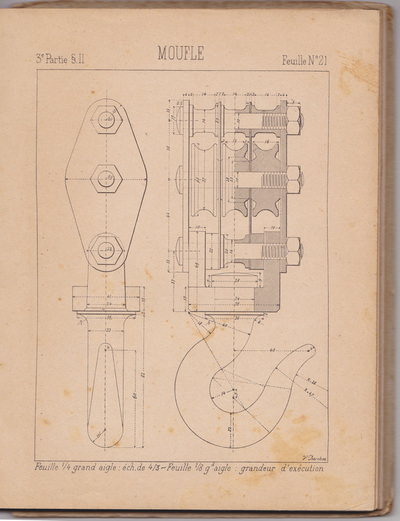

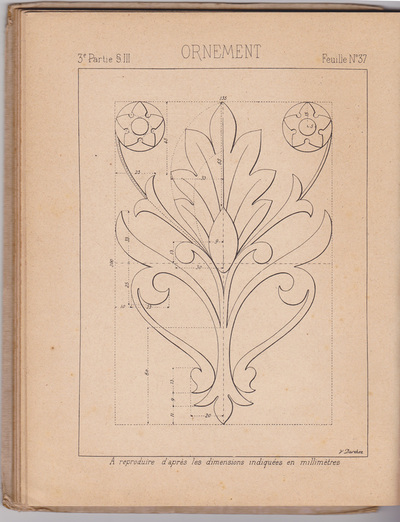

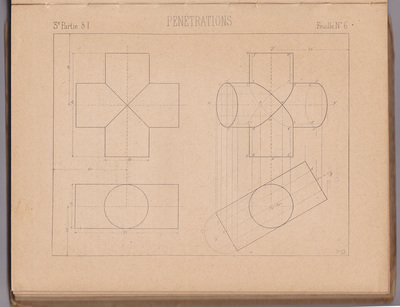

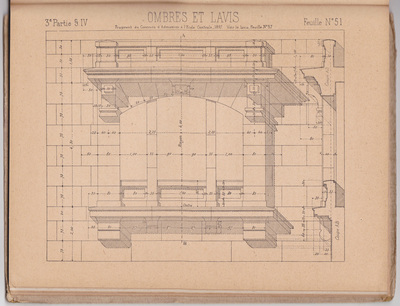

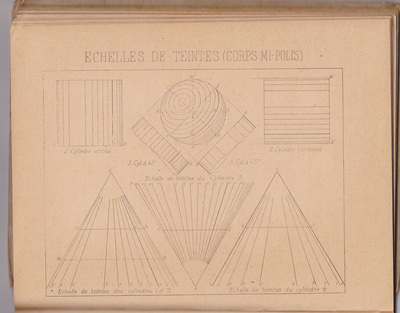

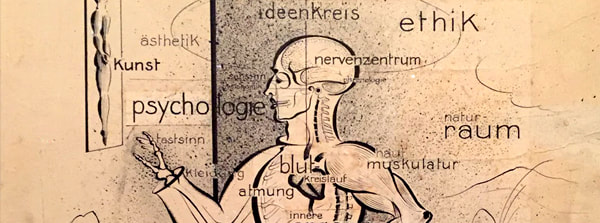

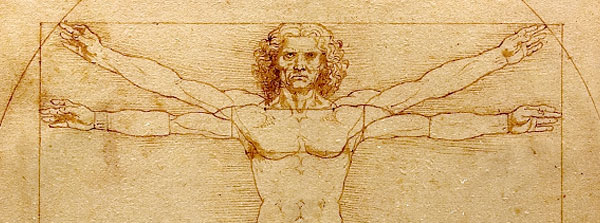

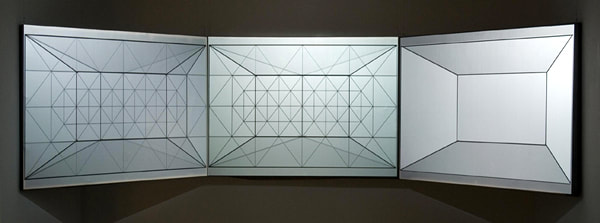

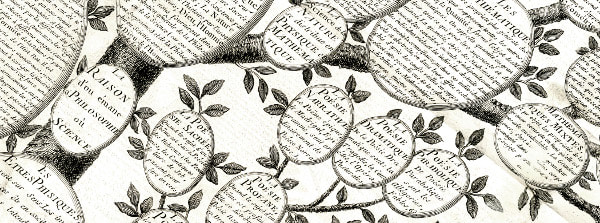

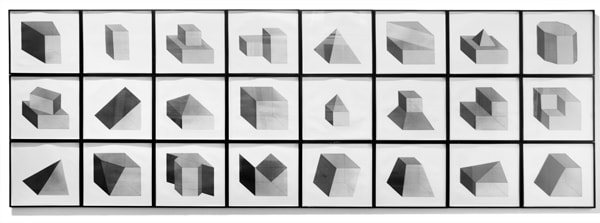

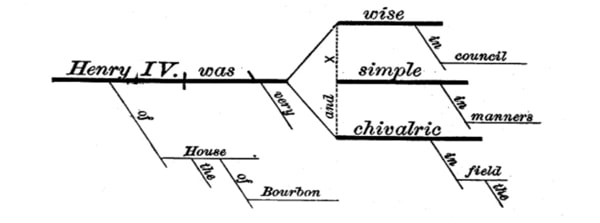

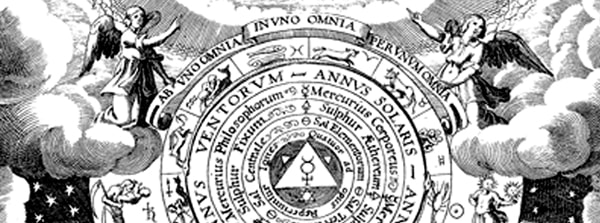

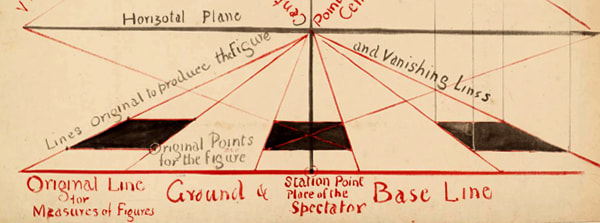

What would happen if you were to change the focus of an entire country's art education system from imitating nature and the human body to mastering the art of technical drawing and creating diagrams ? By the time the French artist Marcel Duchamp was born in 1887, the French national education system had undergone a systematic overhaul and just such changes were already in place in the art departments of each state funded public school. (1) Students of art were no longer expected to study and mimic classical sculpture, the old masters, or the art of the renaissance. Instead, the aim of the new curriculum was fluency in a measured, mechanical drawing style that was refined, skeletal and precise. Referred to as the 'language of industry', this was a whole-sale promotion of a new national, visual language of science, technology and culture in the age of mechanical production. In other words, second only to the epic encyclopedic projects of the 1700's, this was the new dawn of the diagram at the heart of French Culture. In her essay titled 'The language of Industry', Molly Nesbit describes how "by and large this was a language meant for work, not for leisure, and certainly not for raptures or poetic, high cultural sighs. This language was pre-aesthetic, a public culture based upon mechanical drawings, sans colour, sans nature, sans body, sans the classics, some would have said sans everything." (2) Within the class rooms, drawing courses were divided in to depicting objects in perspective (objects reproduced the way they appear to the eye) and in projection (objects depicted as ideal forms, independent of a human observer and the optics of our two human eyes). Because of this distinction, French art students were taught to make a fundamental distinction between apparent and true representation, just as Duchamp himself would later make a similar distinction between what he called retinal and non-retinal art.

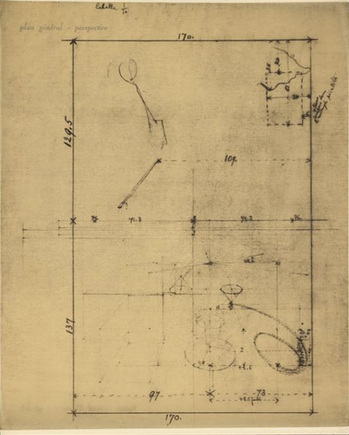

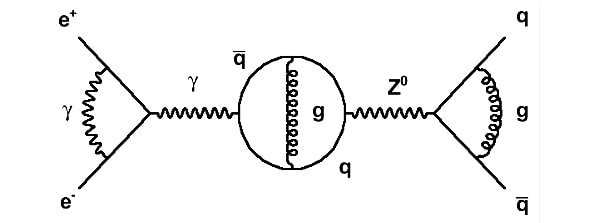

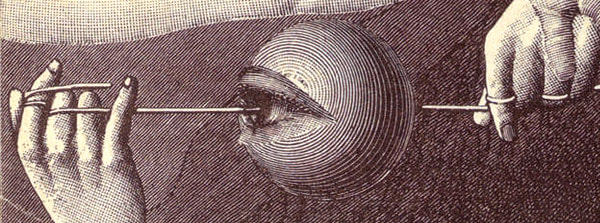

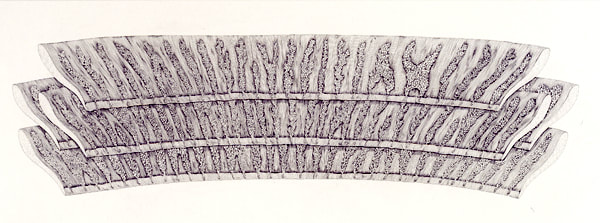

Marcel Duchamp went on to develop his artistic use of diagrams and diagramming in a number of important ways, from the one dimensional plumb lines that he dropped to make '3 standard stoppages' (a work which questions the one dimensional meter as a standard unit of length), to his intricate two dimensional sketches for 'The Large Glass' which suggest archetypal lines and platonic skeletal forms in higher dimensions.

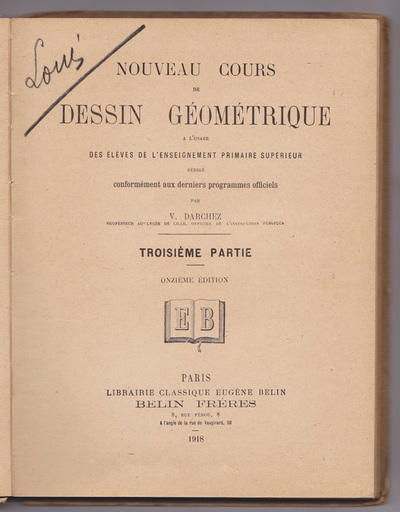

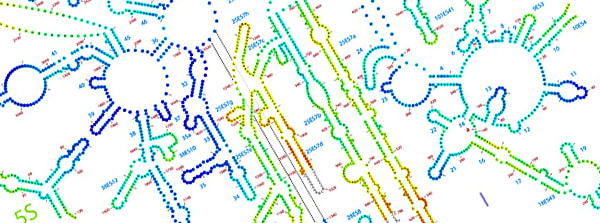

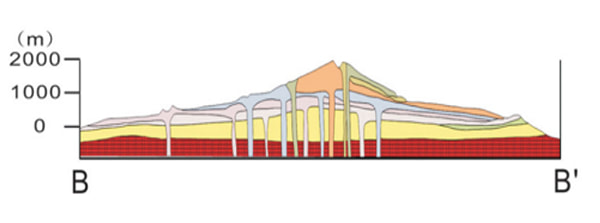

Duchamp's various projects embodied a more general shift in science and culture, from drawing as a representation of the natural world, to drawing as a means of depicting the technical nature of the structural and functional systems which underlie reality, as described by science and mathematics, but always by means of the diagram. The following diagrams were scanned from the third book in the series "Nouveau Cours de Dessin géométrique", compiled by Professor V. darchez of the state-funded secondary school in Lyon. The director of the Beaux-Arts School in Paris at the time, the sculptor and critic Eugène Guillaume, elaborated upon the new program of diagrammatic training: "Drawing is by its very nature exact, scientific, authoritative. It images with undeniable precision (to which one must submit) things such as they are or as they appear. Not one of its configurations could not be analyzed, verified, transmitted, understood, realized. In its geometrical sense, as in perspective, drawing is written and is read: it has the character of a universal language." (6) References:

1) The 'Ferry Reforms' of the French national school system were established during the 1870s and 80s. 2) Nesbit, M. The Language of industry (1991). In: The Definitely unfinished Marcel Duchamp, MIT Press, 1991, p.356. 3) Duchamp, M. interview with Dorothy Norman, first published in Art in America, Vol.57, July -Aug. 1969. p38. 4) Duchamp, M. In: Schwarz, A. The Complete works of Marcel Duchamp, revised and expanded edition, New York, 1997, p.573. 5) Duchamp, M. In; Ades, D., Cox, N., Hopkins, D. Marcel Duchamp, london, 1999, p.75. 6) Nesbit, M. The Language of industry (1991). In: The Definitely unfinished Marcel Duchamp, MIT Press, 1991, p.372. Comments are closed.

|

Dr. Michael WhittleBritish artist and Posts:

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|